- About W3C and the Web

- Why accessibility is important

- Why internationalization is important

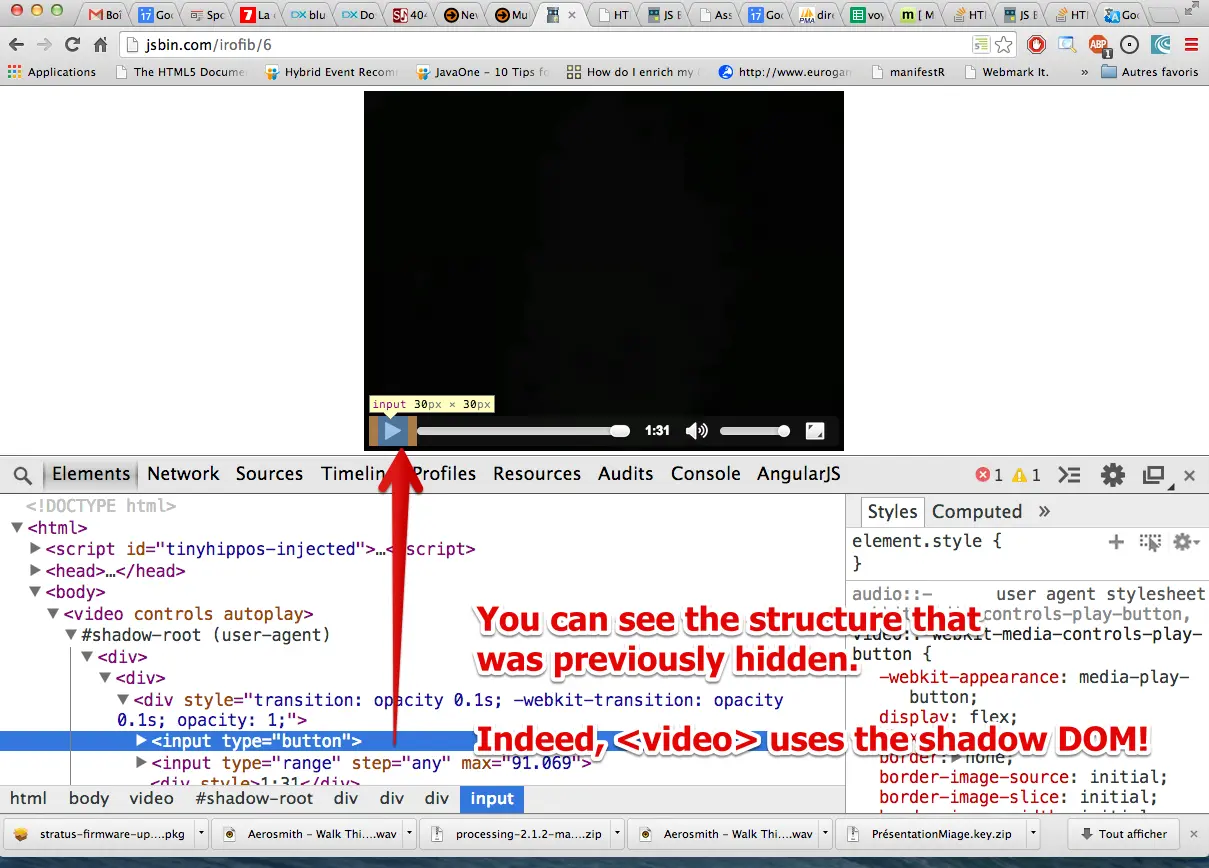

1.1. Introduction - Advanced HTML5 Multimedia

1.2. The Timed Text Track API

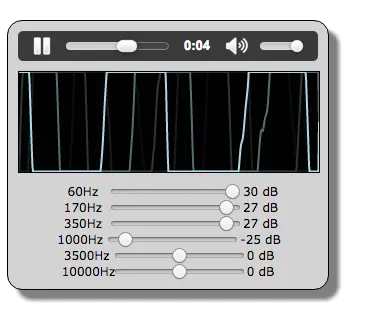

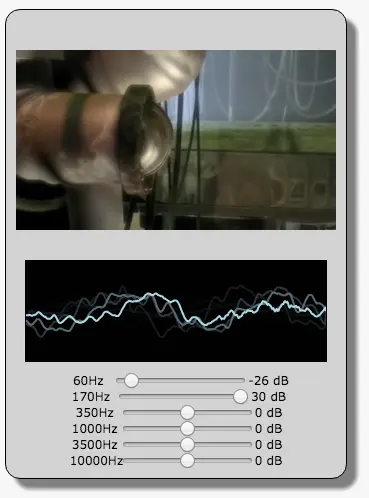

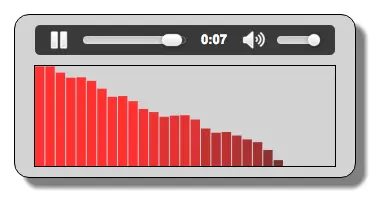

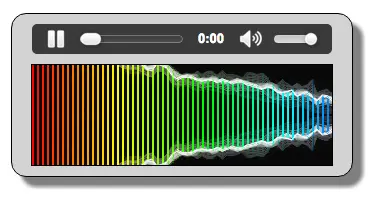

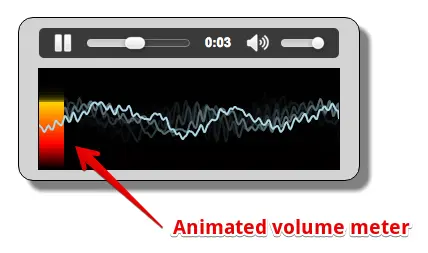

1.3. Advanced Features for Audio and Video Players

1.4. Creating Tracks on the Fly, Syncing HTML Content With a Video

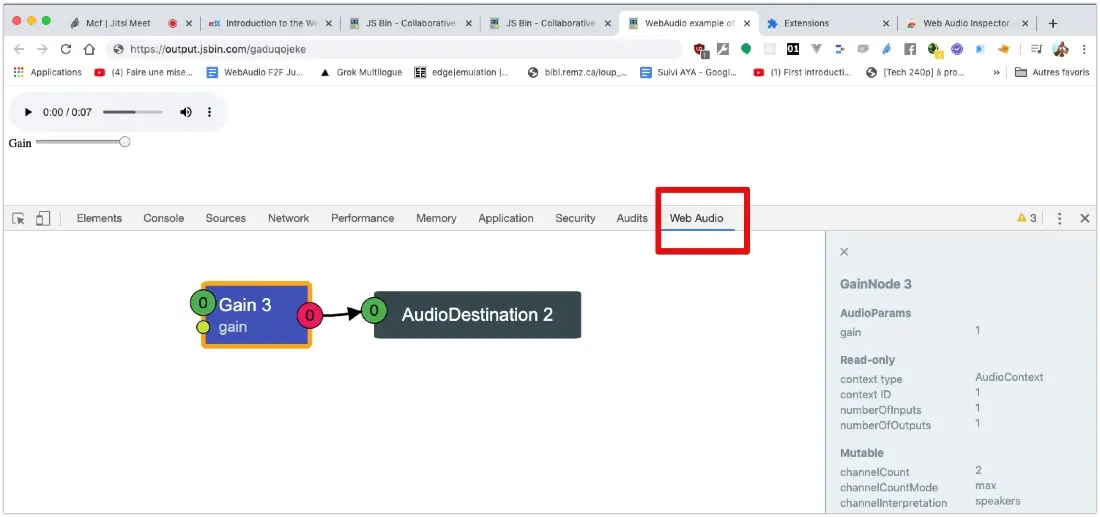

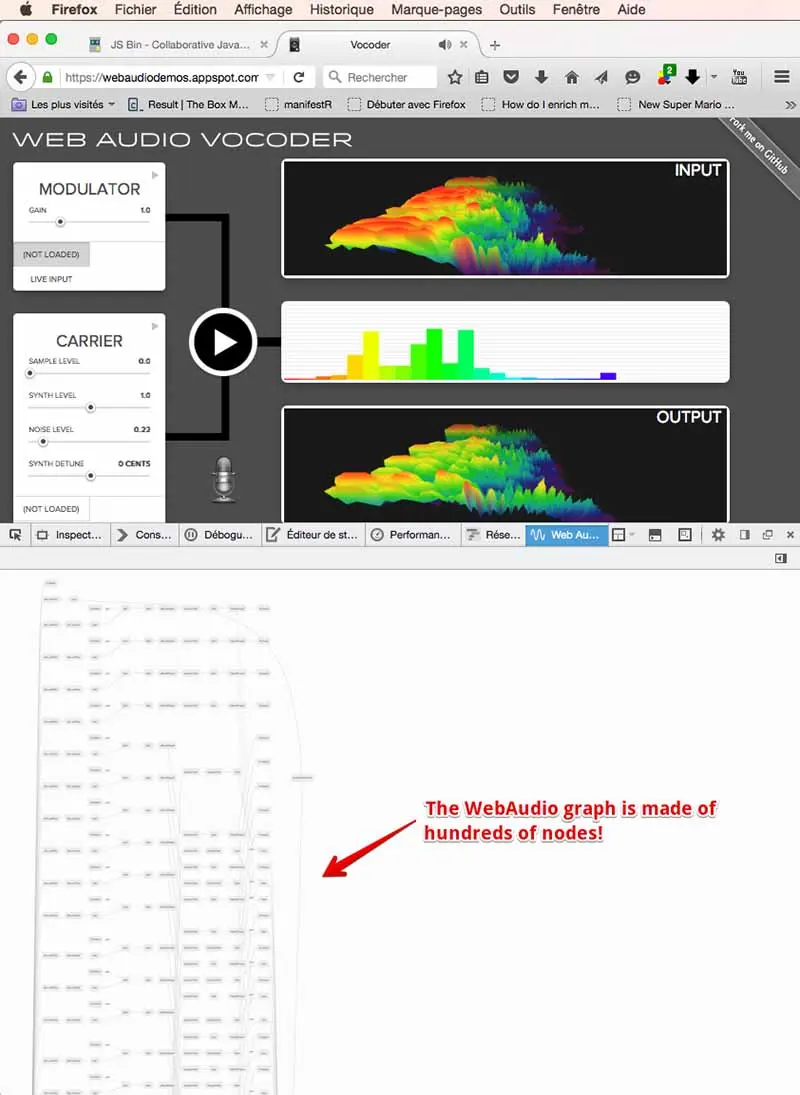

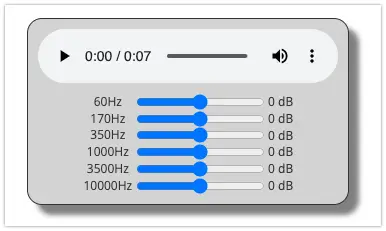

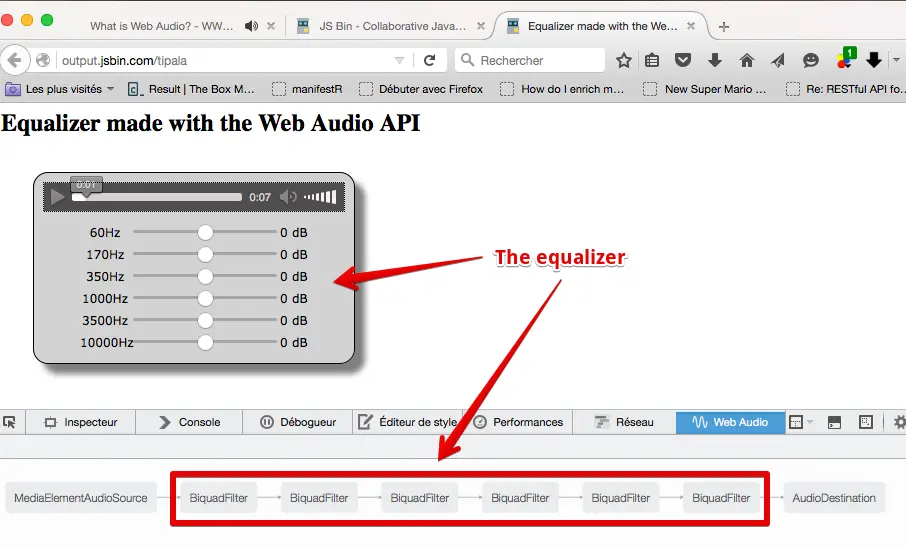

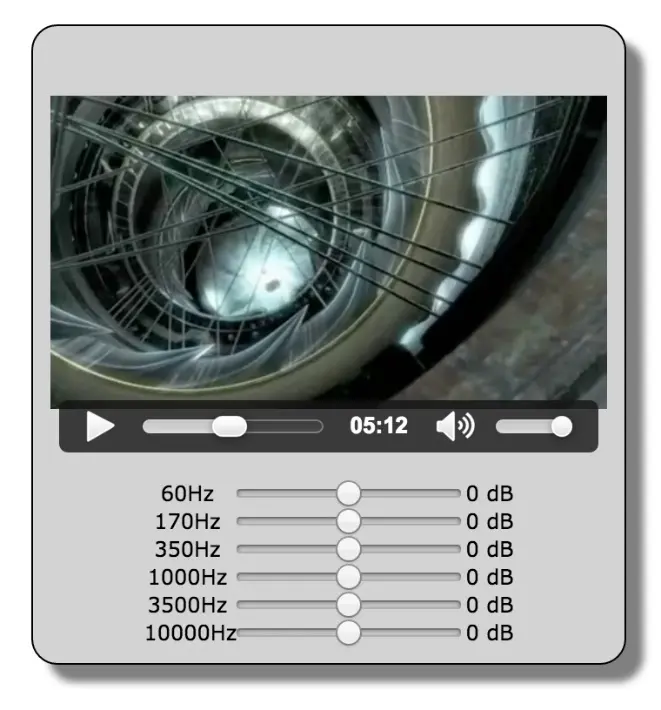

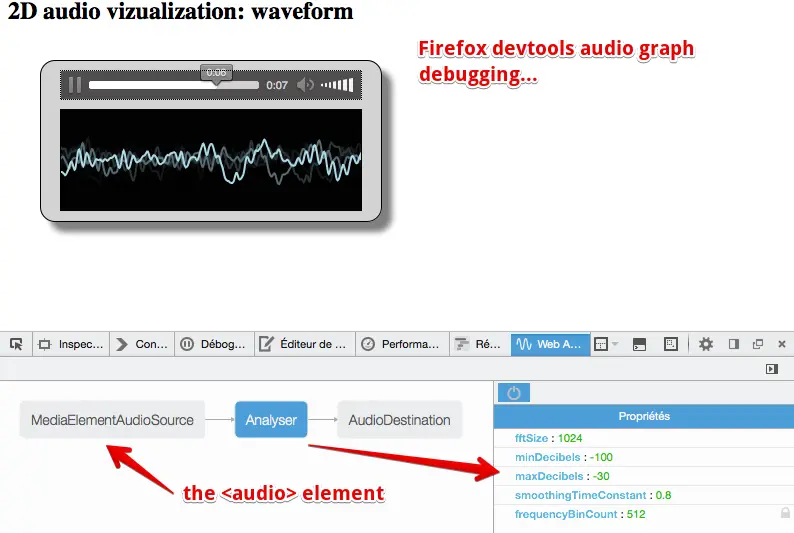

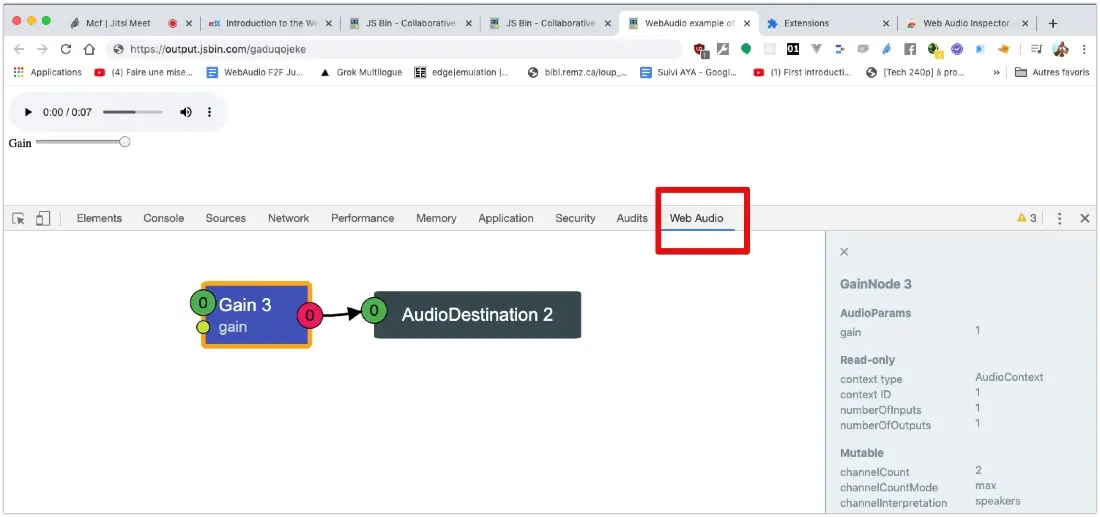

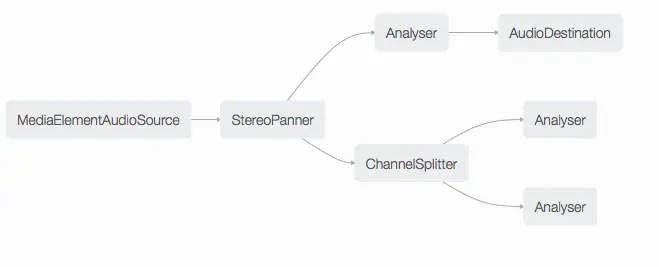

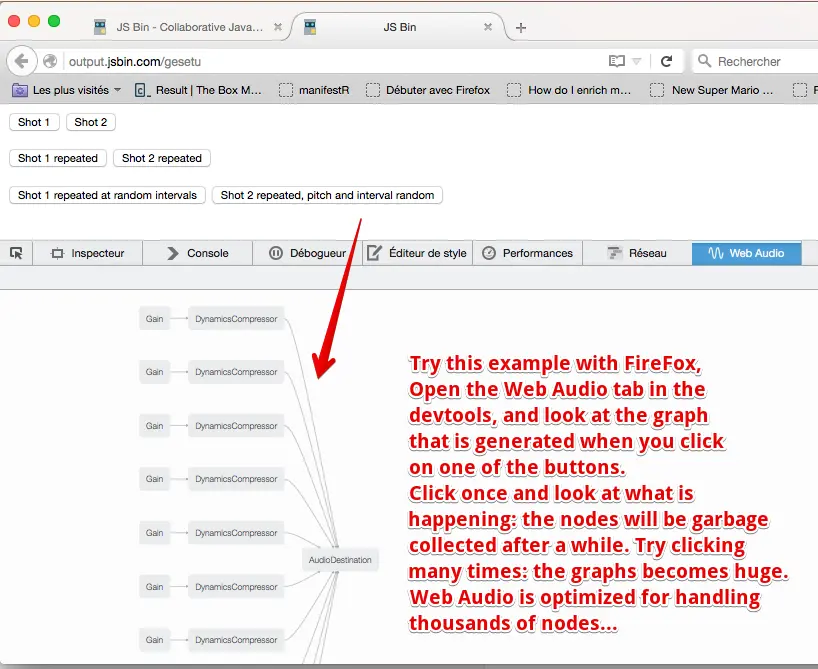

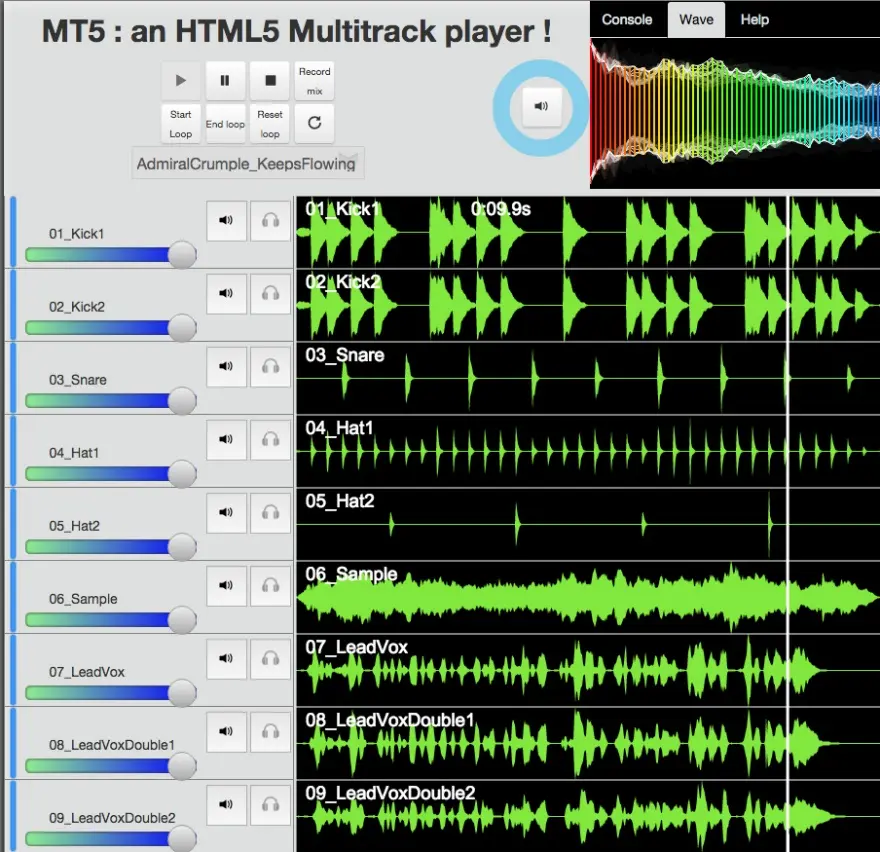

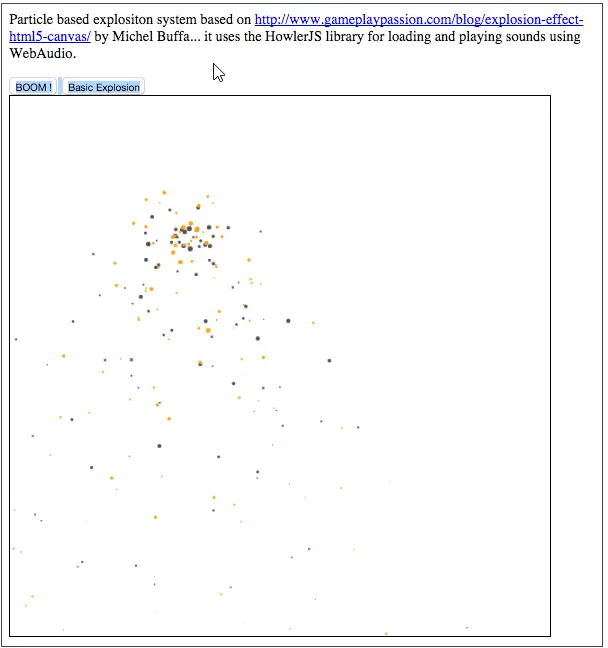

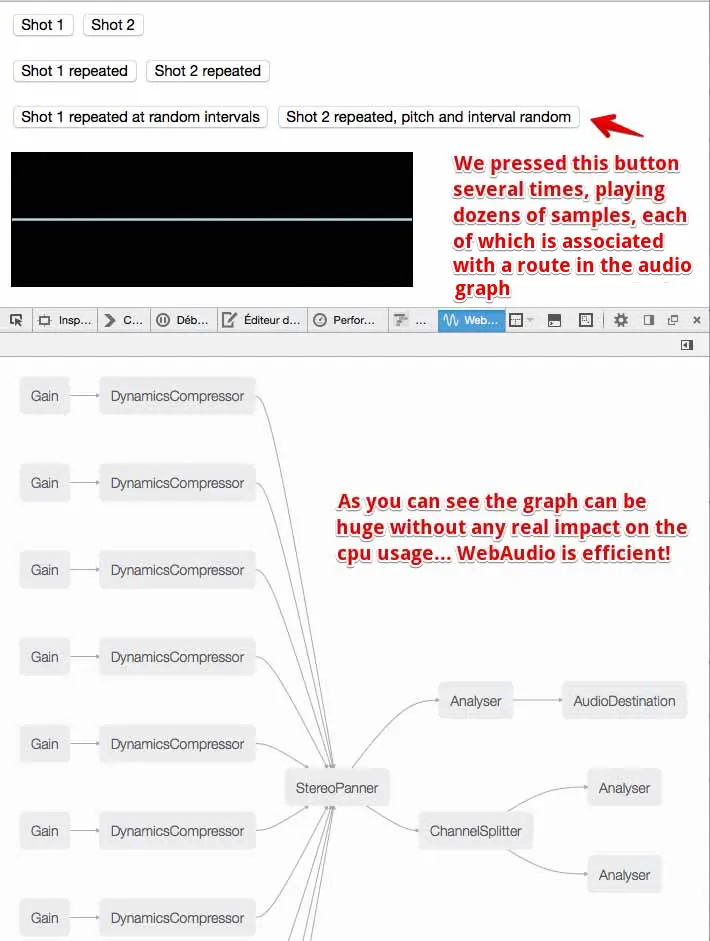

1.5. The Web Audio API

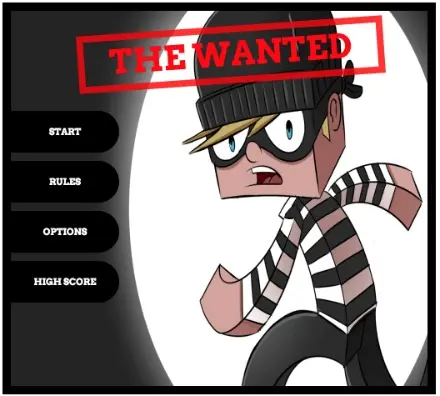

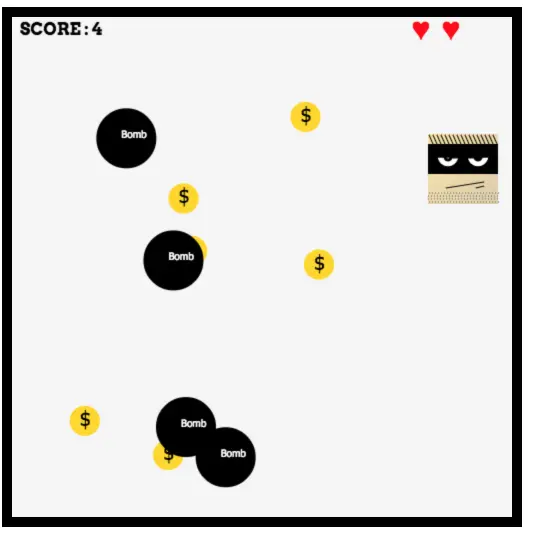

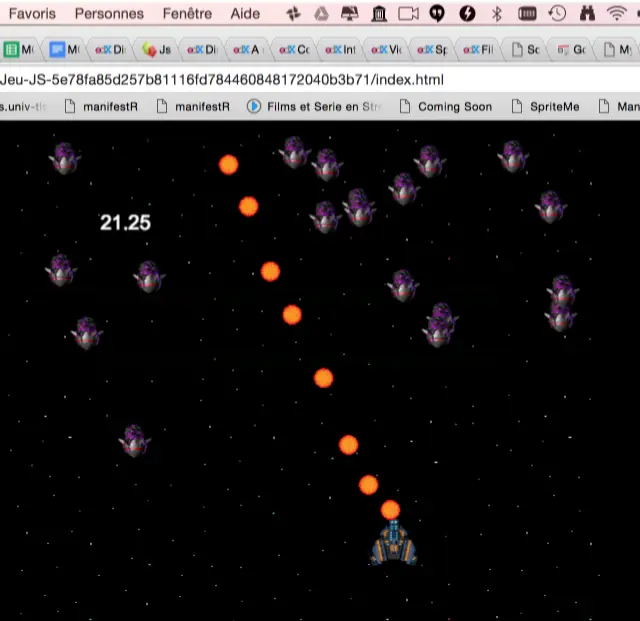

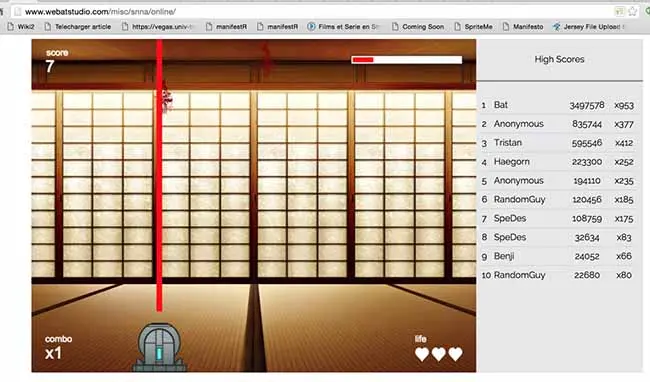

2.1. Introduction - Game Programming with HTML5

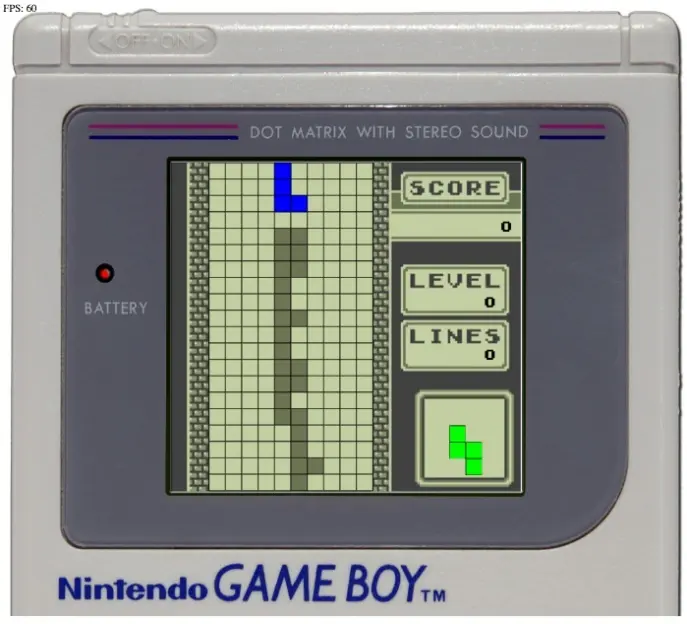

2.2. History of JavaScript Game Development

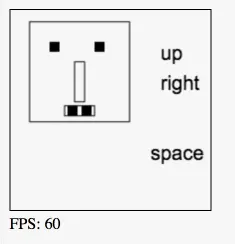

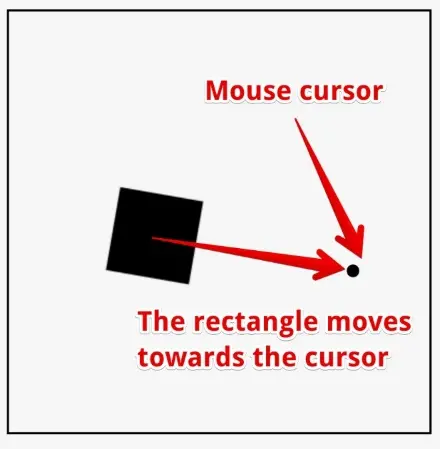

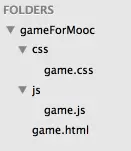

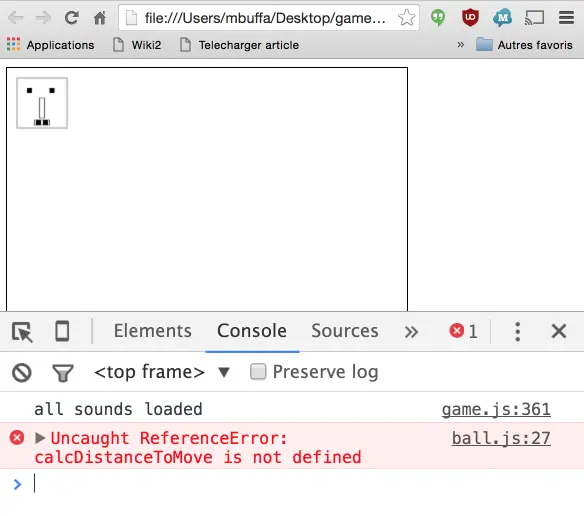

2.3. A Simple Game Framework: Graphics, Animations and Interactions

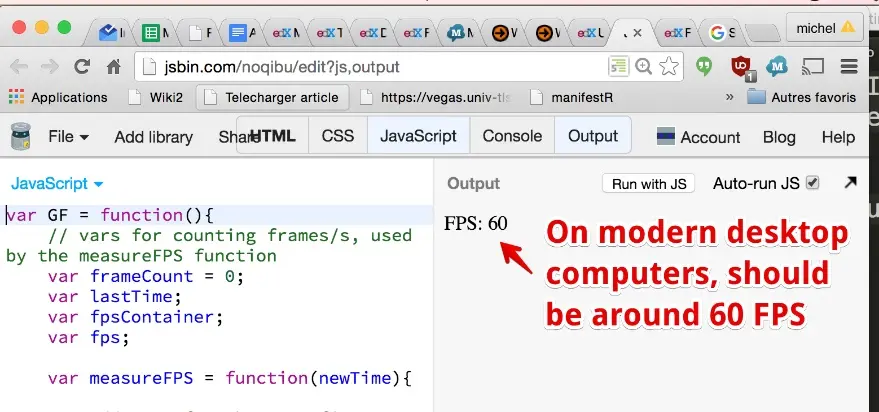

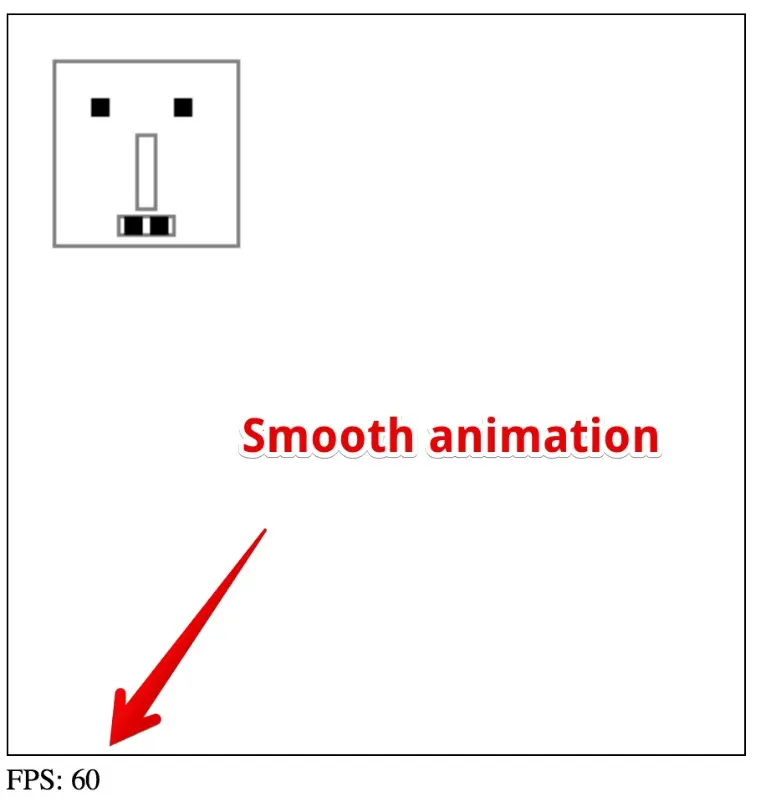

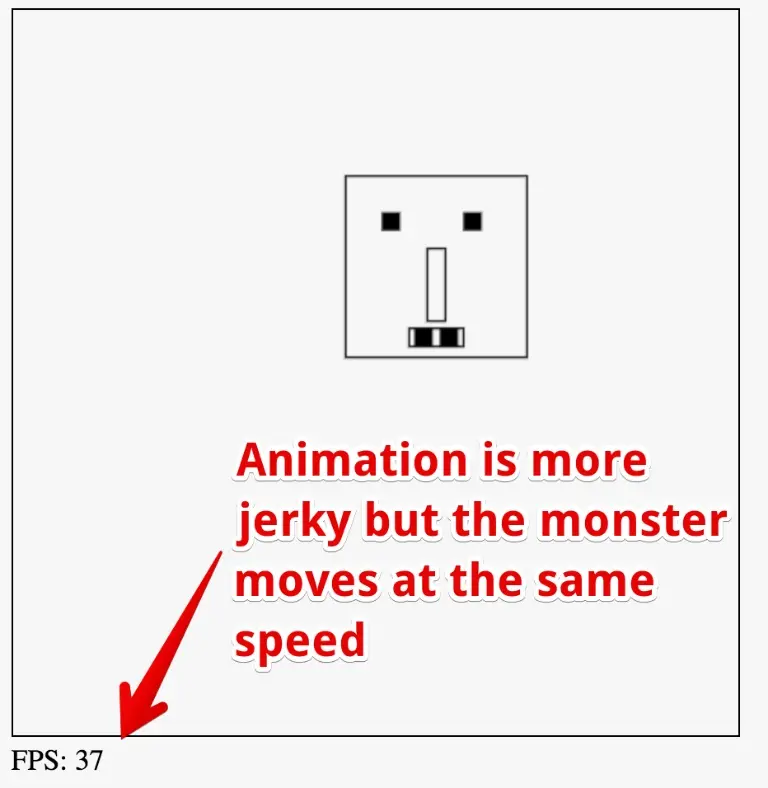

2.4. Time-based Animation

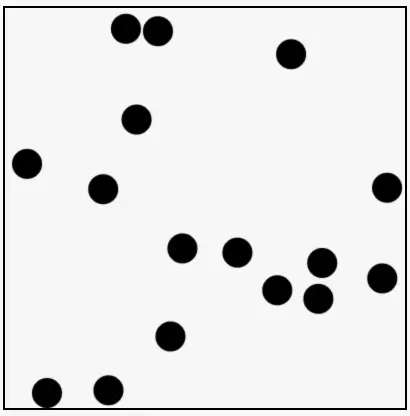

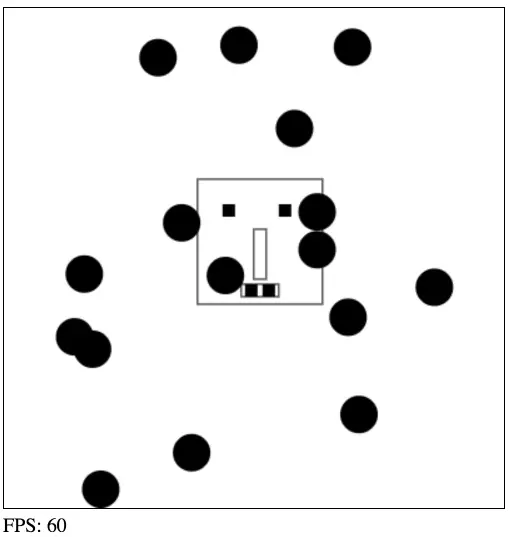

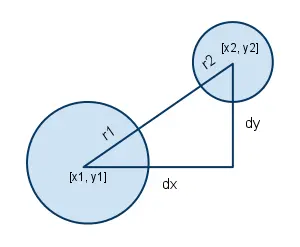

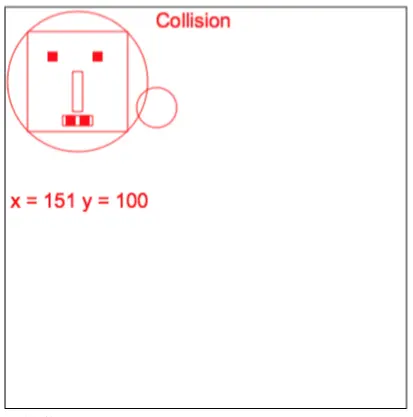

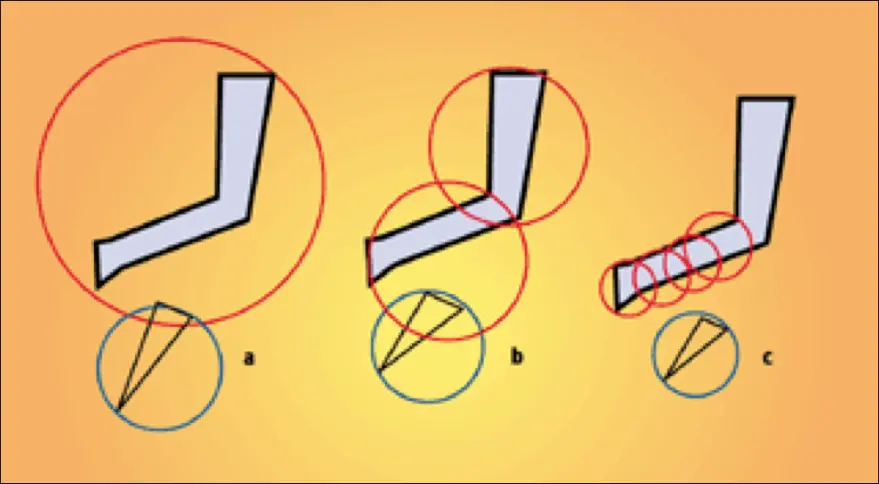

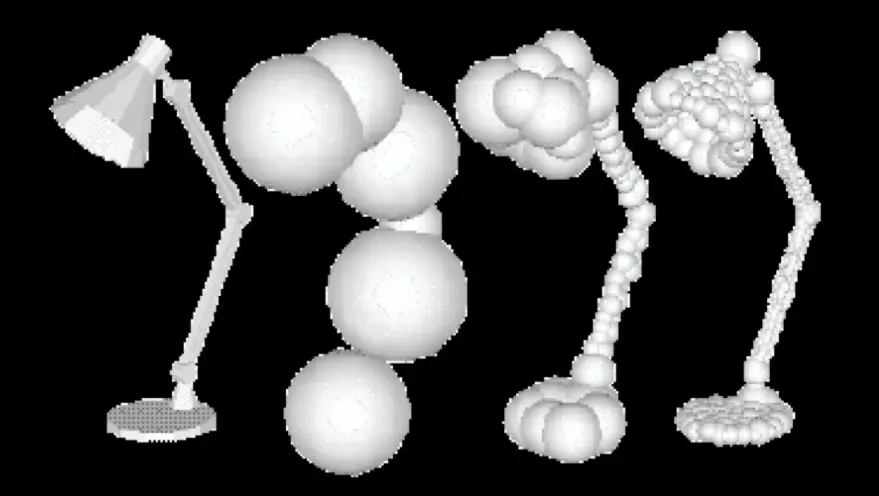

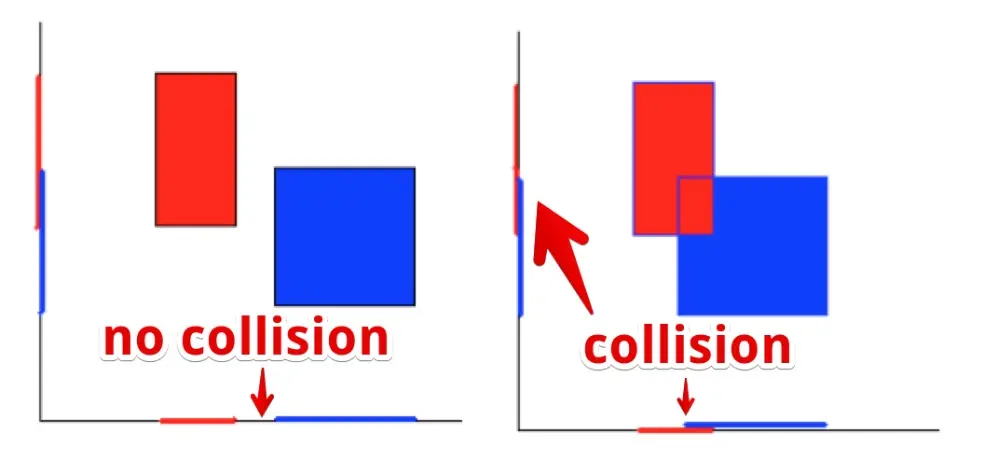

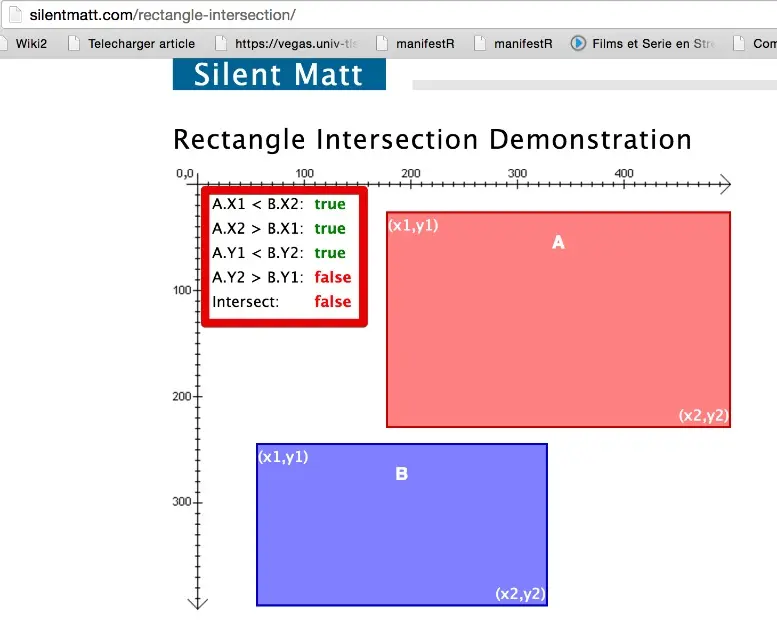

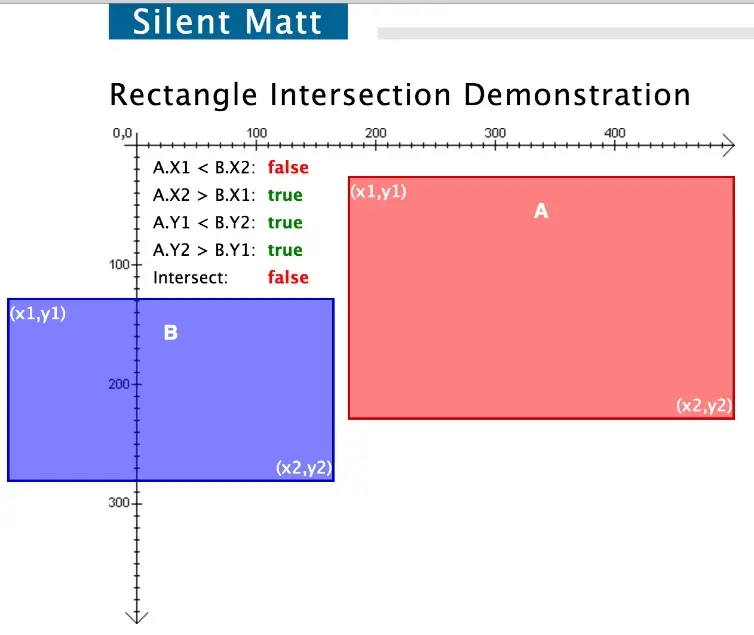

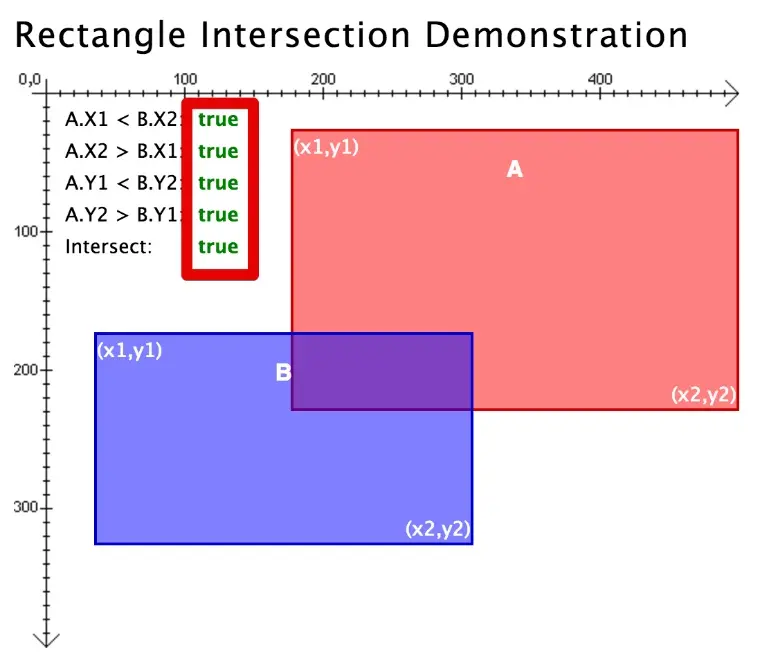

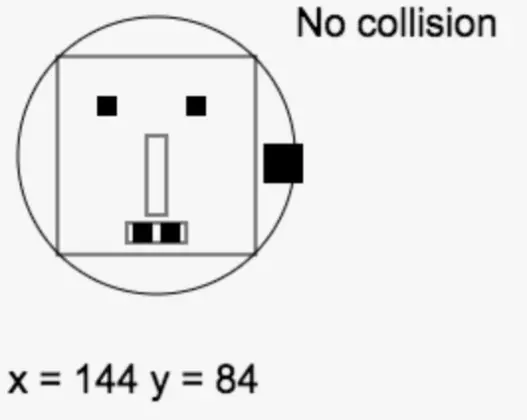

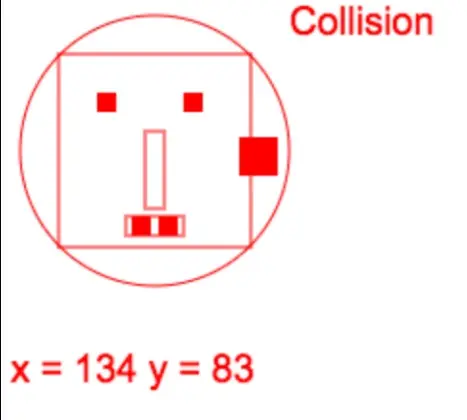

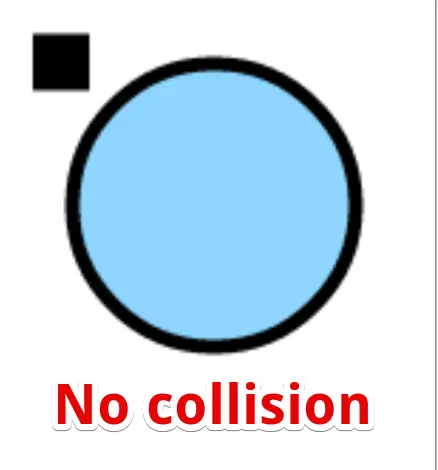

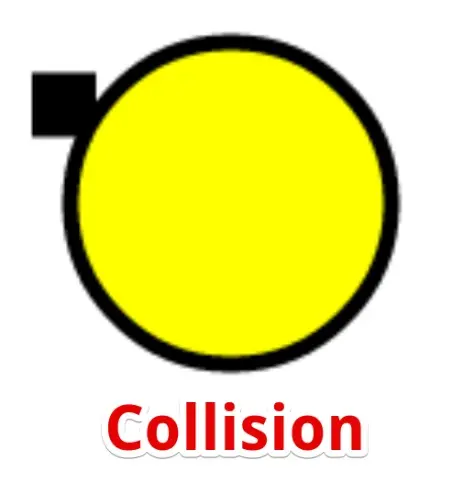

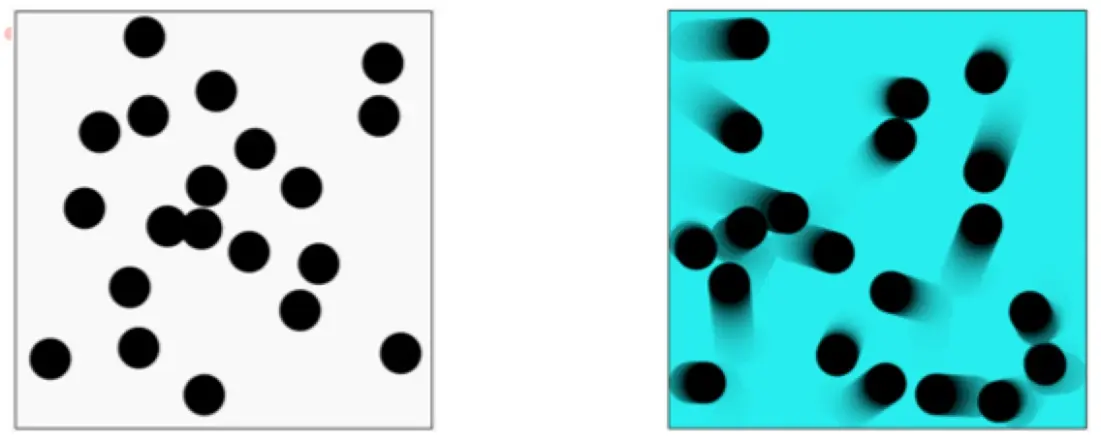

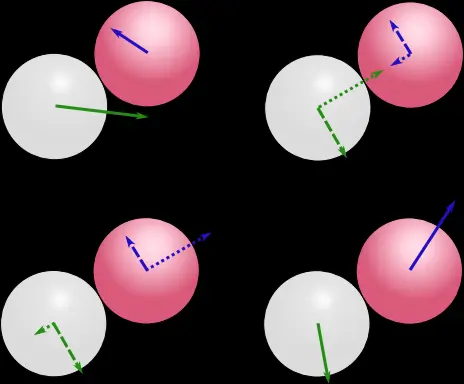

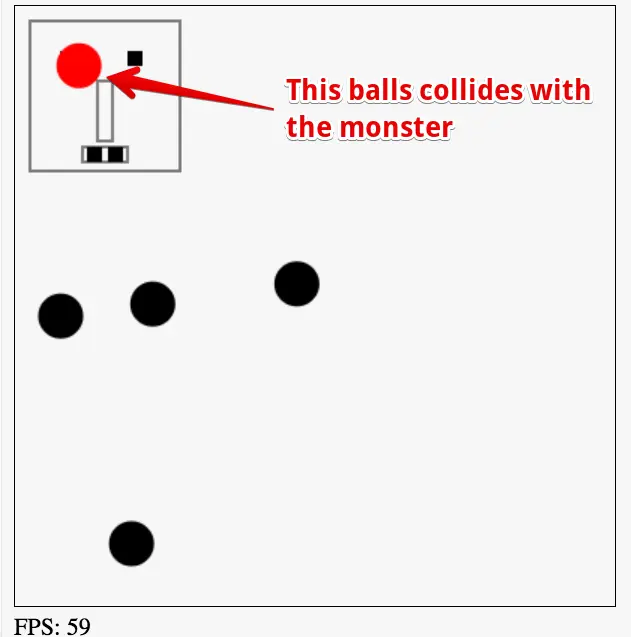

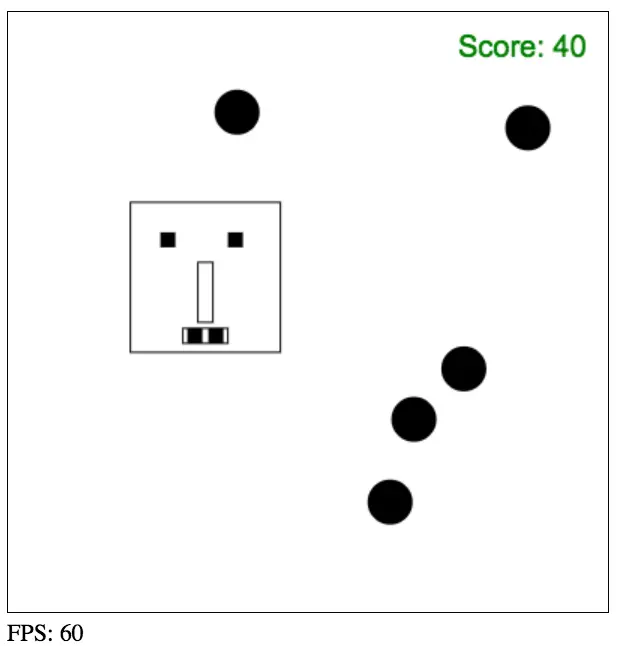

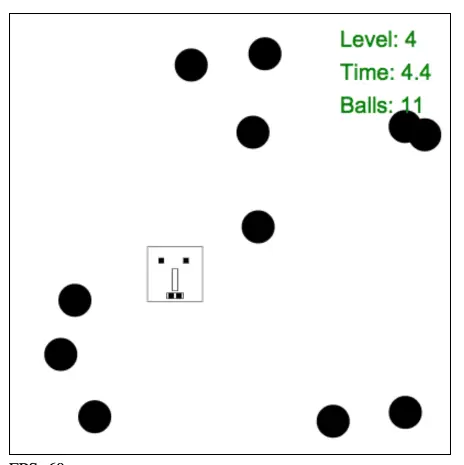

2.5. Animating Multiple Objects, Collision Detection

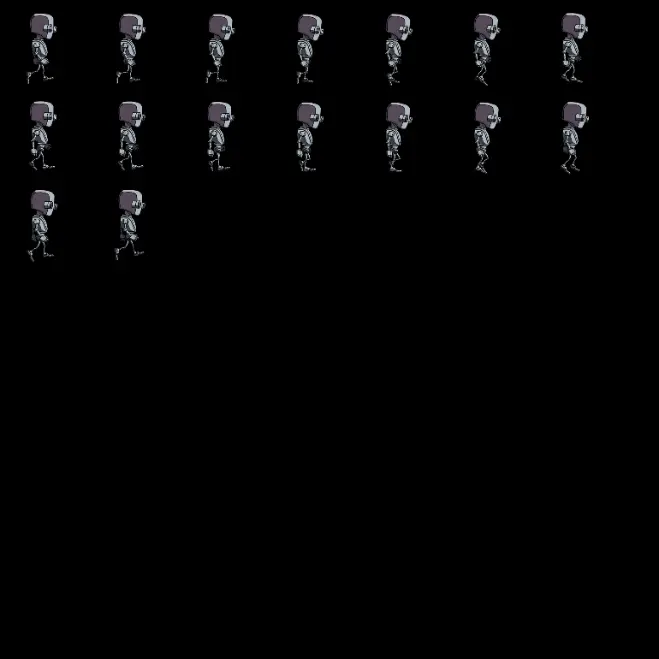

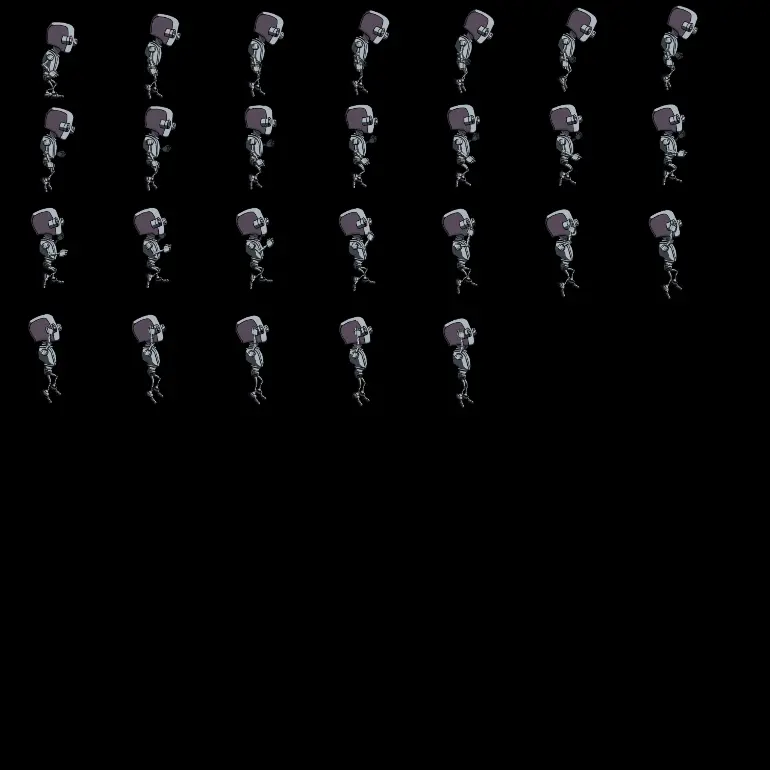

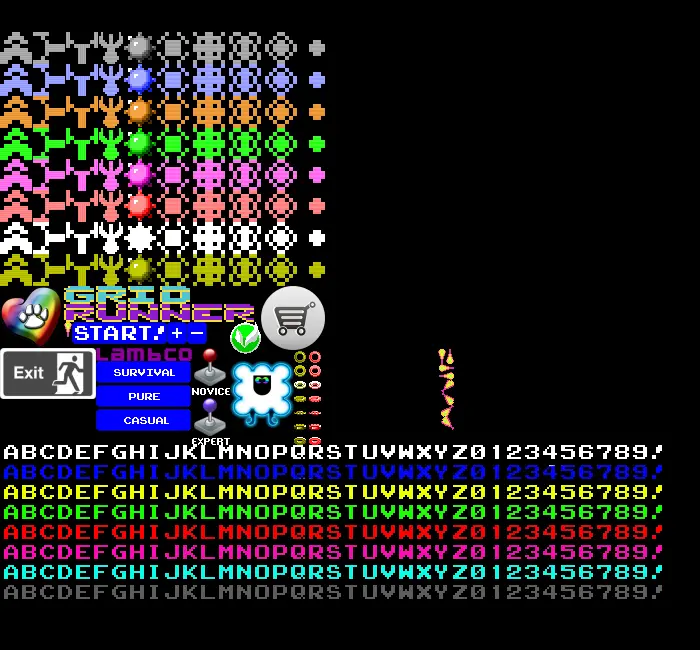

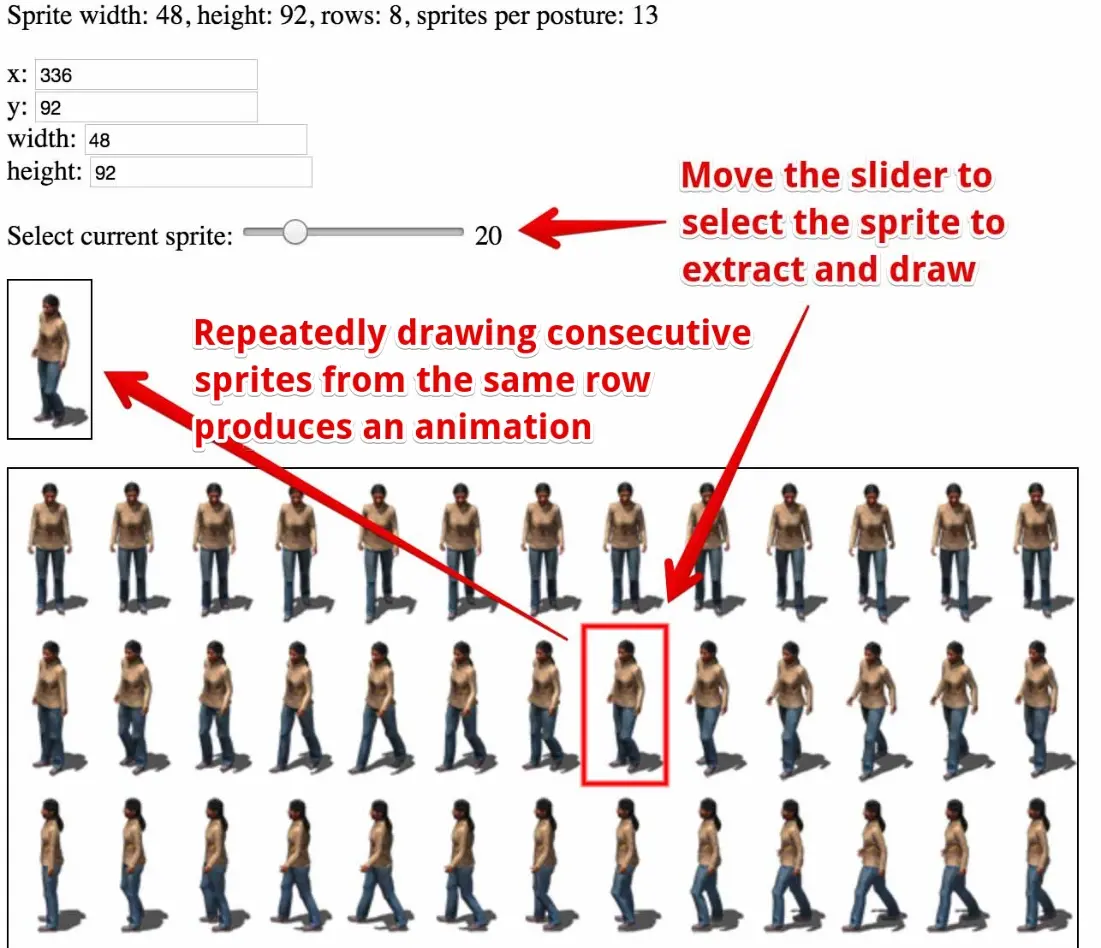

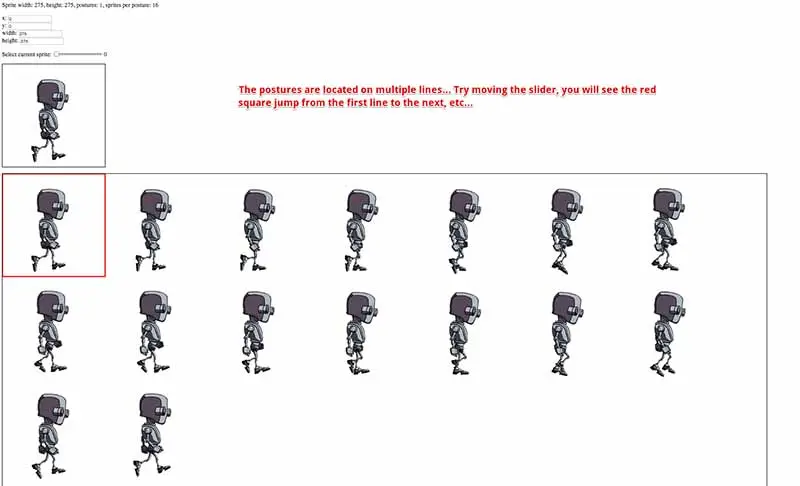

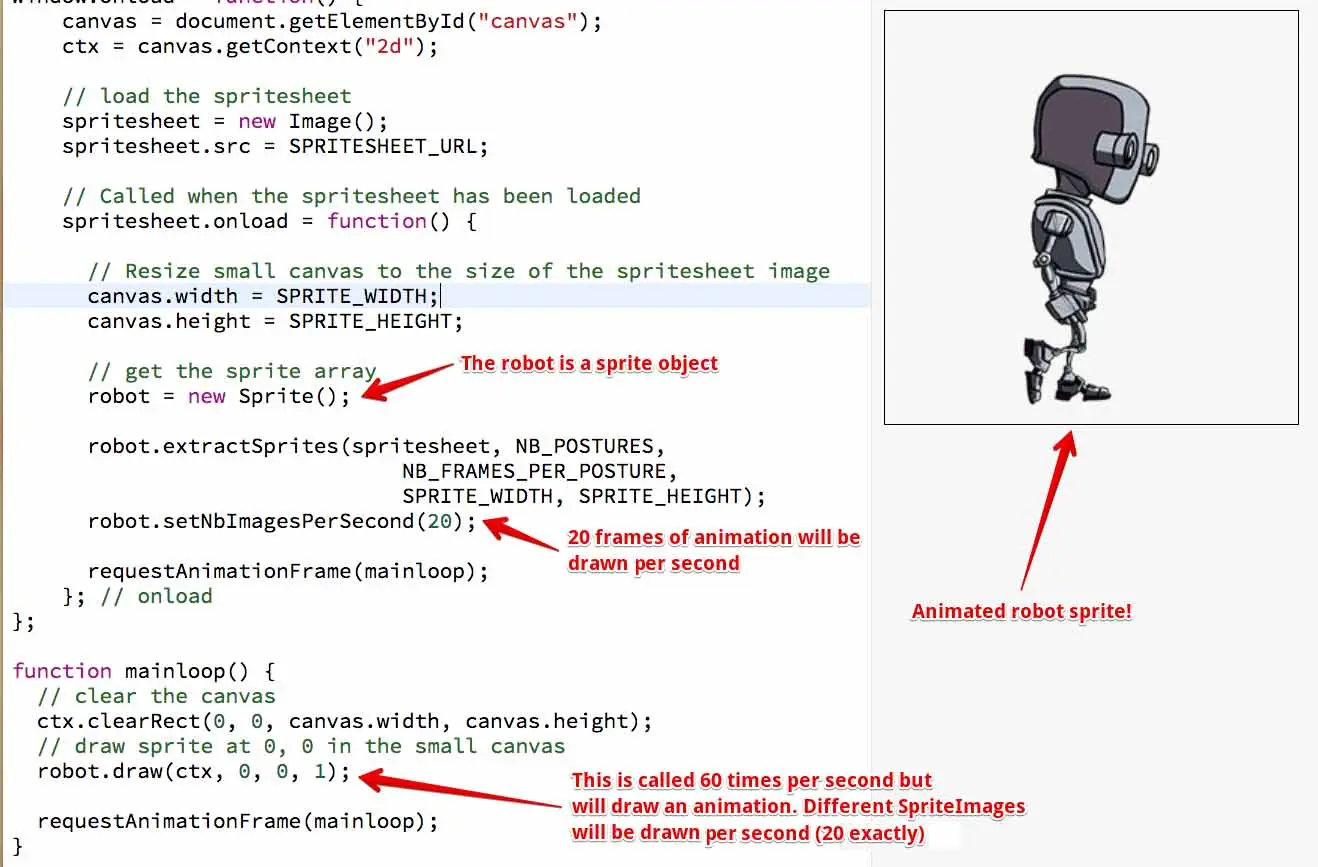

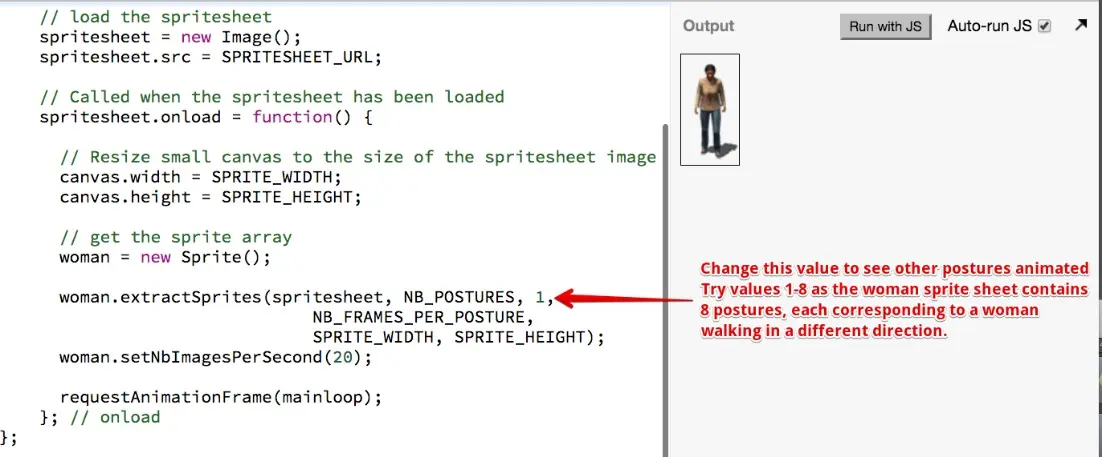

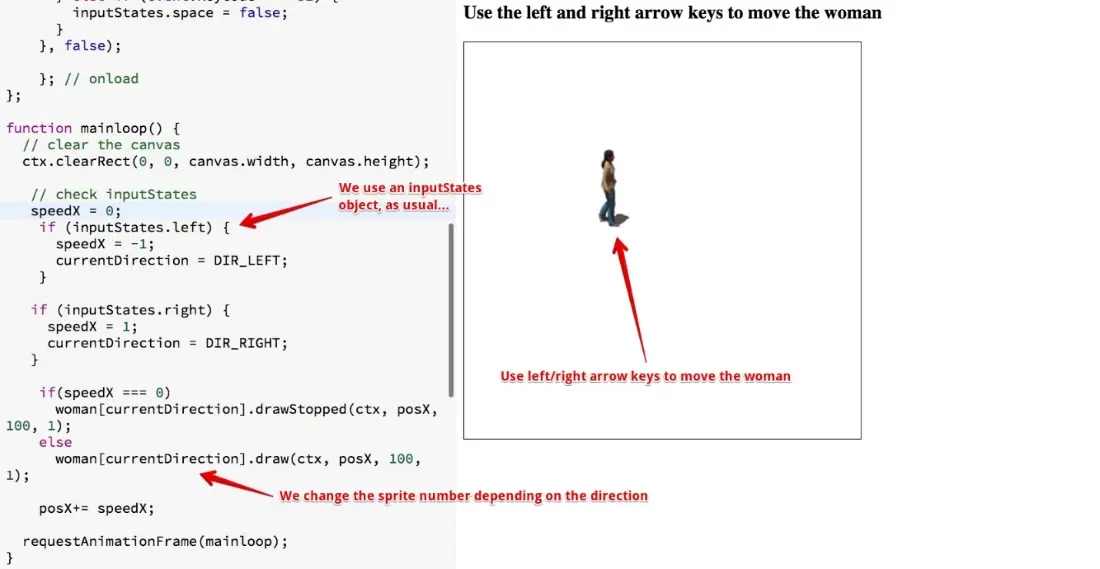

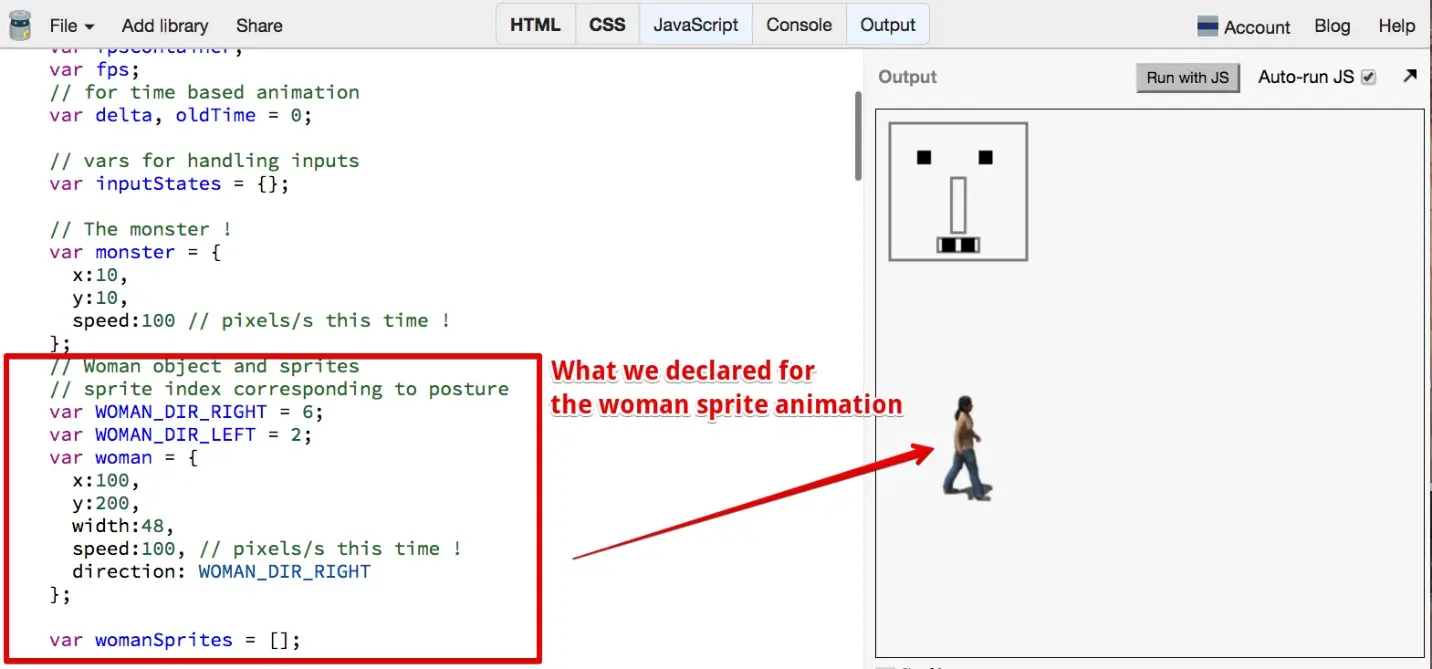

2.6. Sprite-based Animation

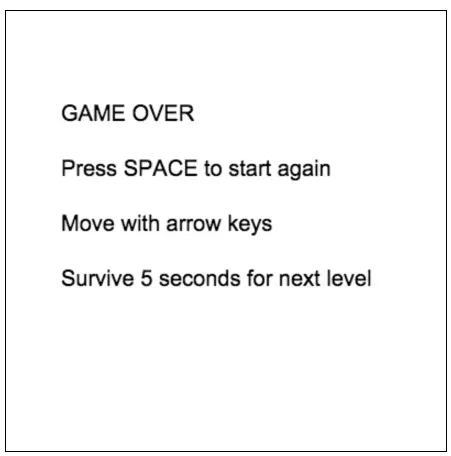

2.7. Game States

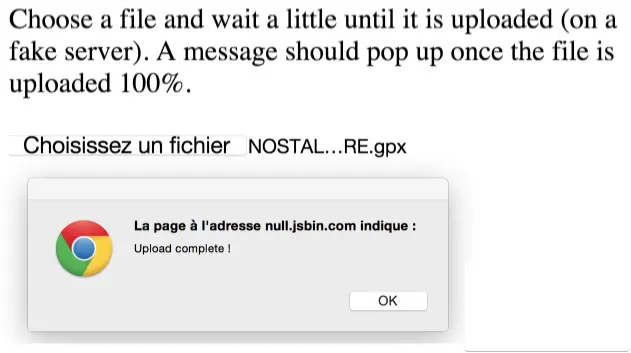

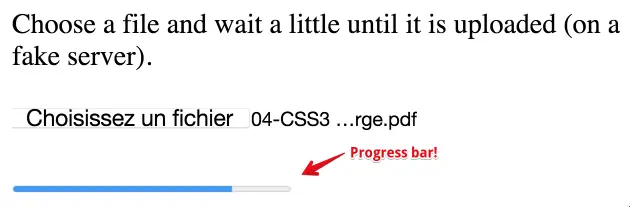

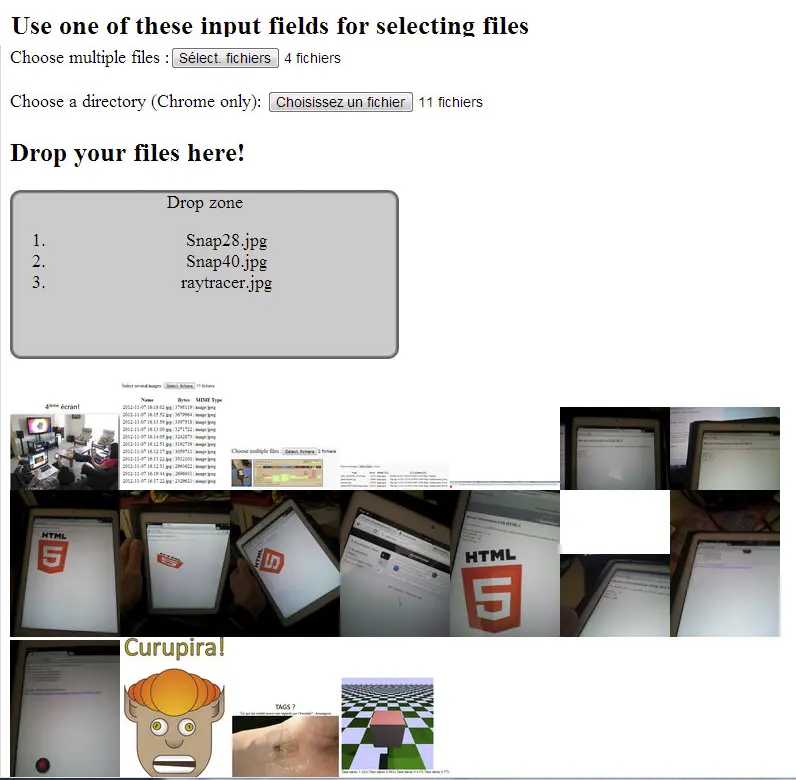

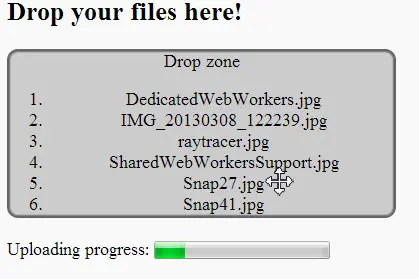

3.1. Introduction - HTML5 File Uploads & Downloads

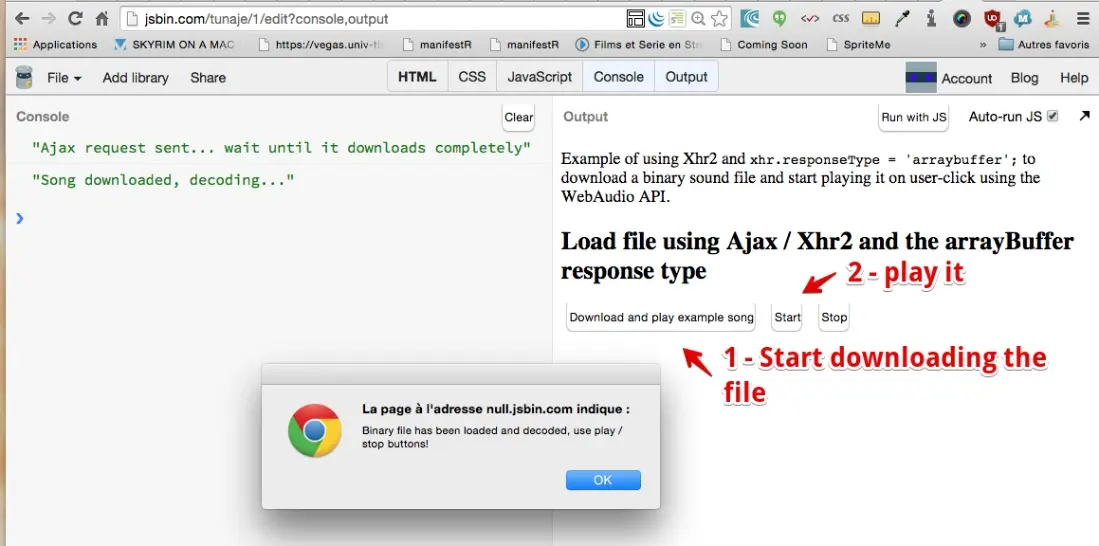

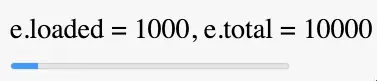

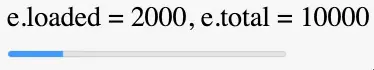

3.2. File API and Ajax / XHR2 Requests

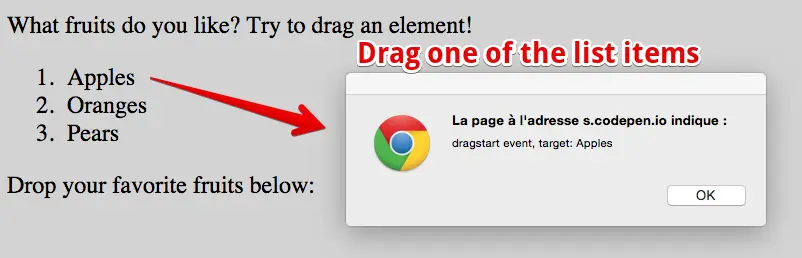

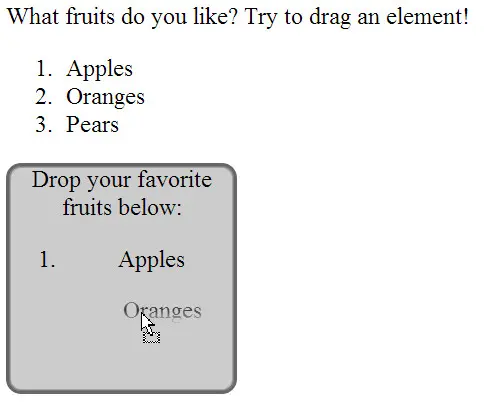

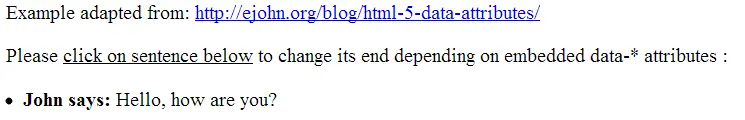

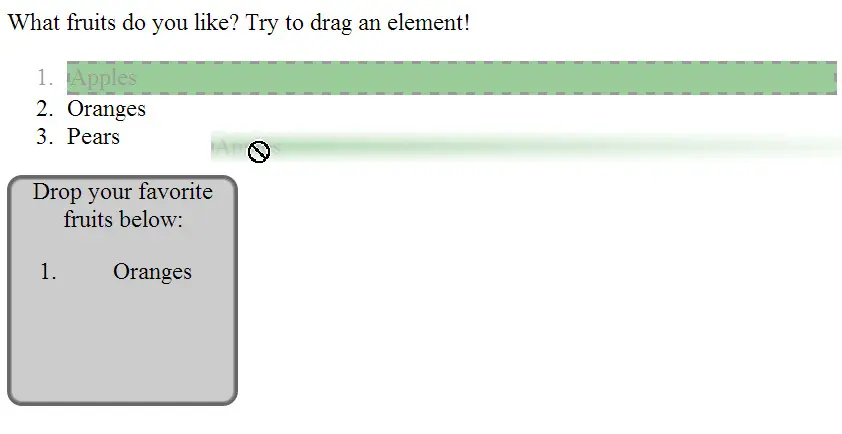

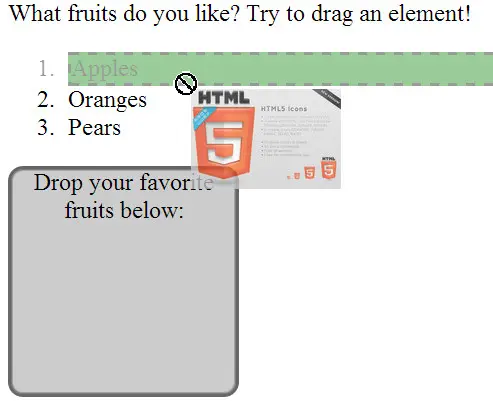

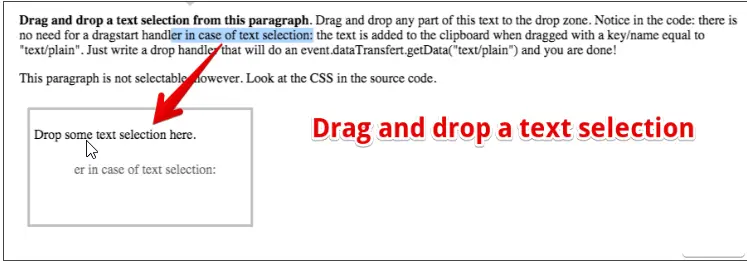

3.3. Drag and Drop: the Basics

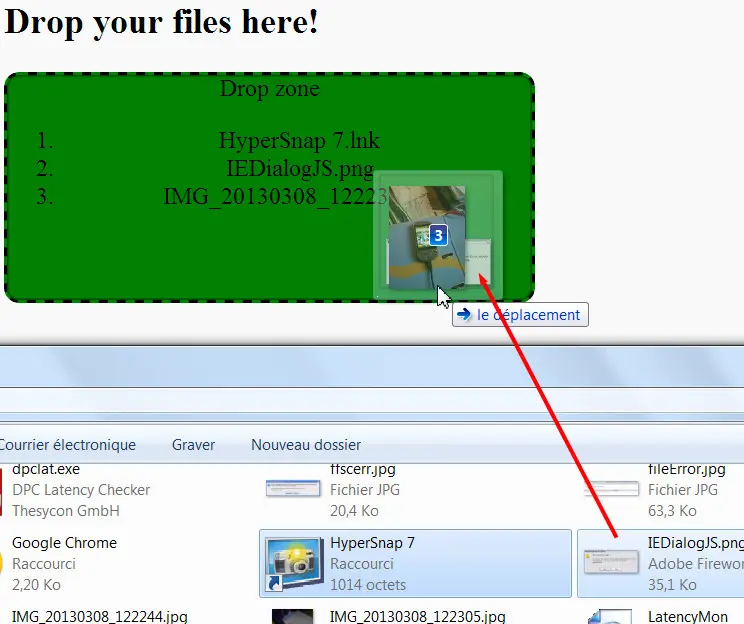

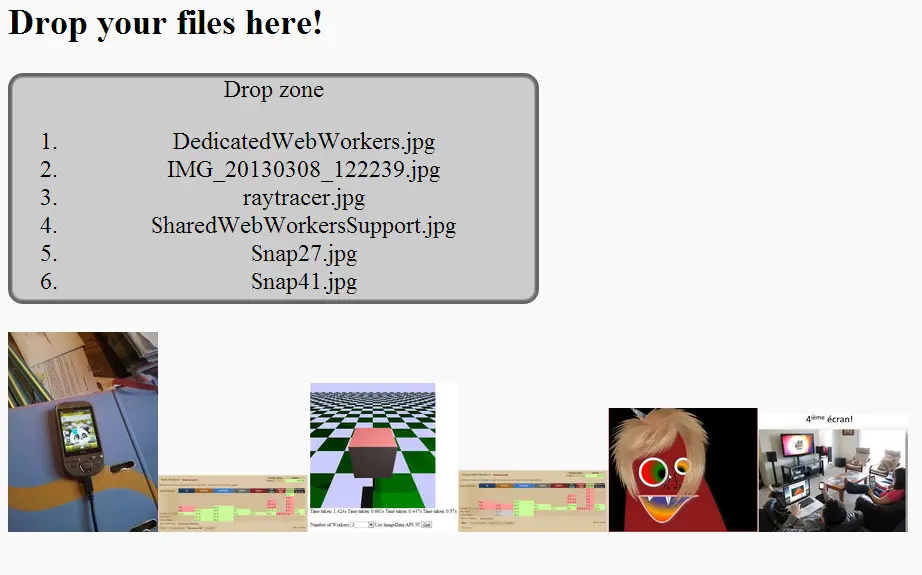

3.4. Drag and Drop: Working with Files

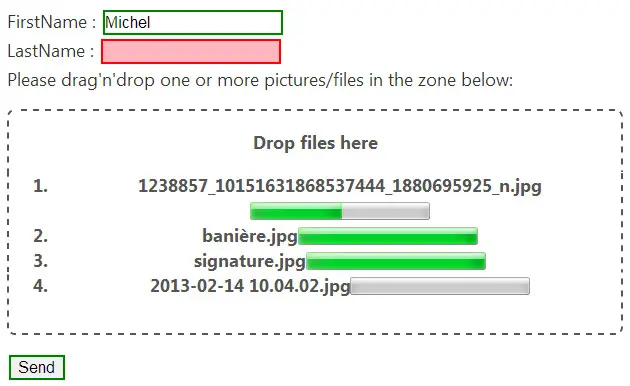

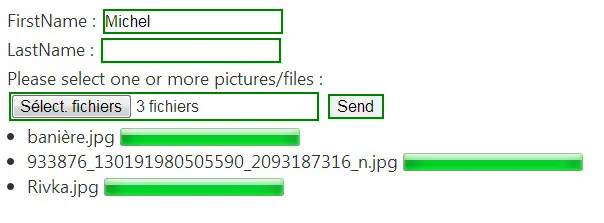

3.5. Forms and Files

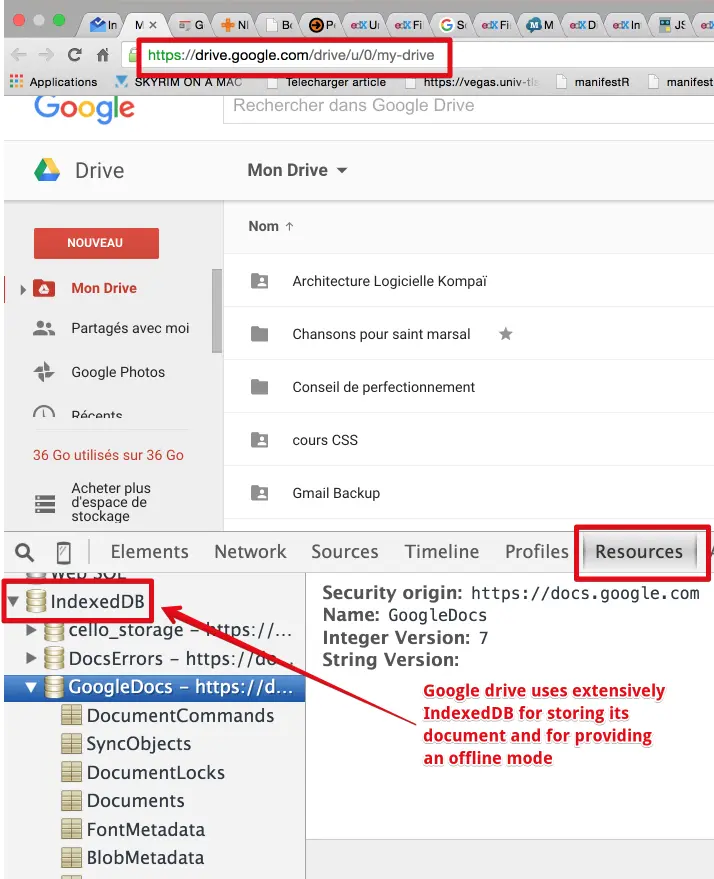

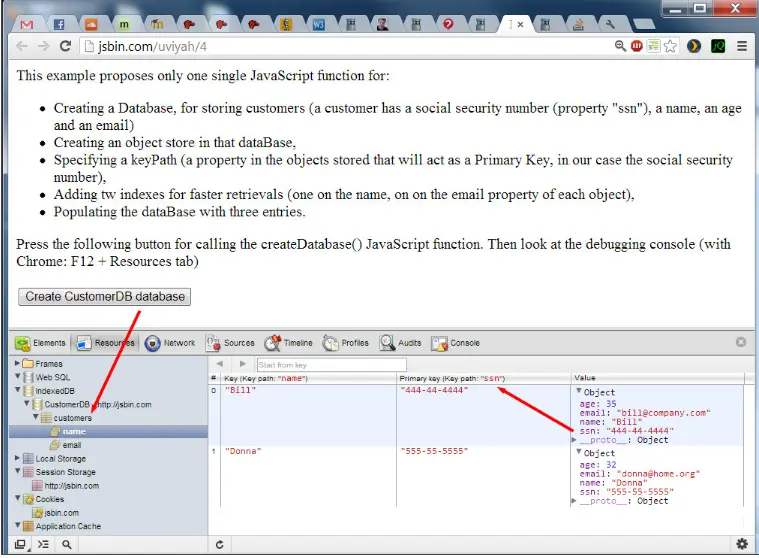

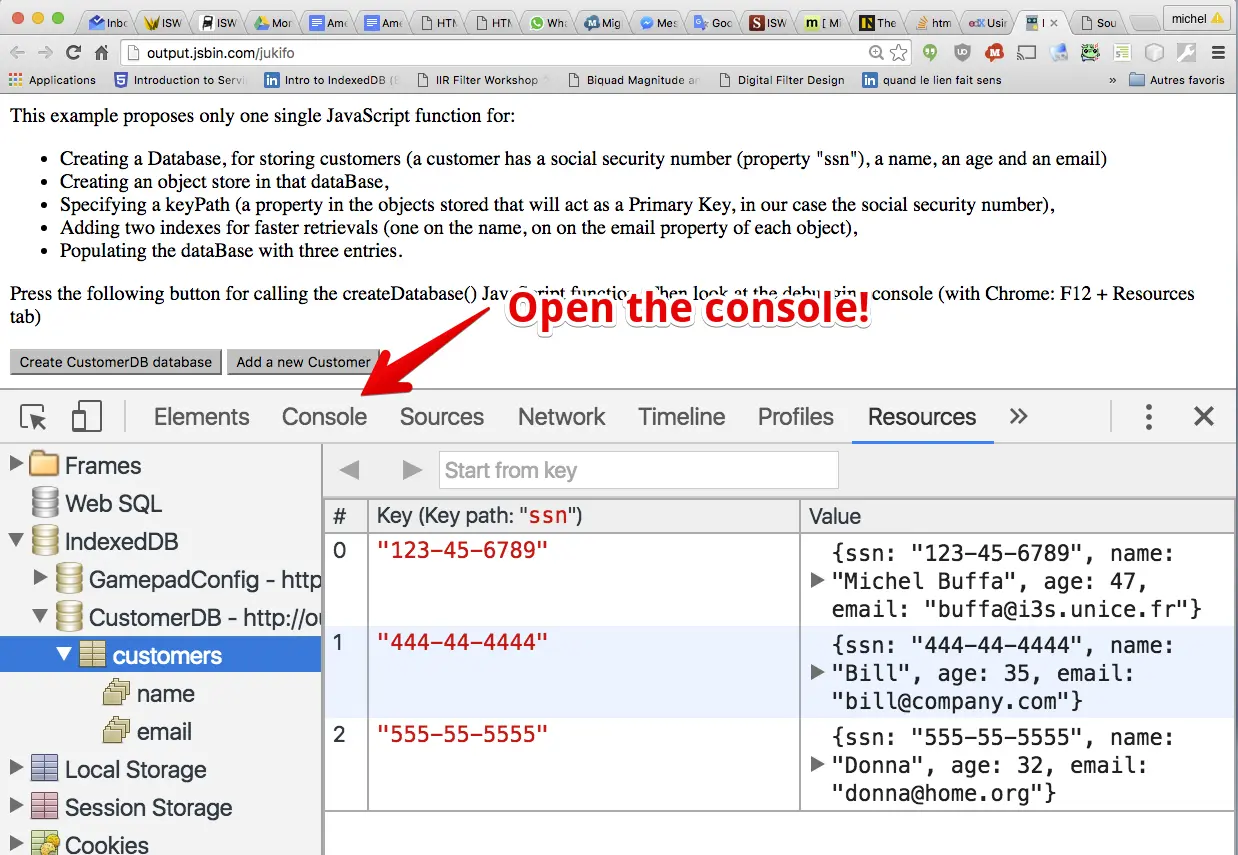

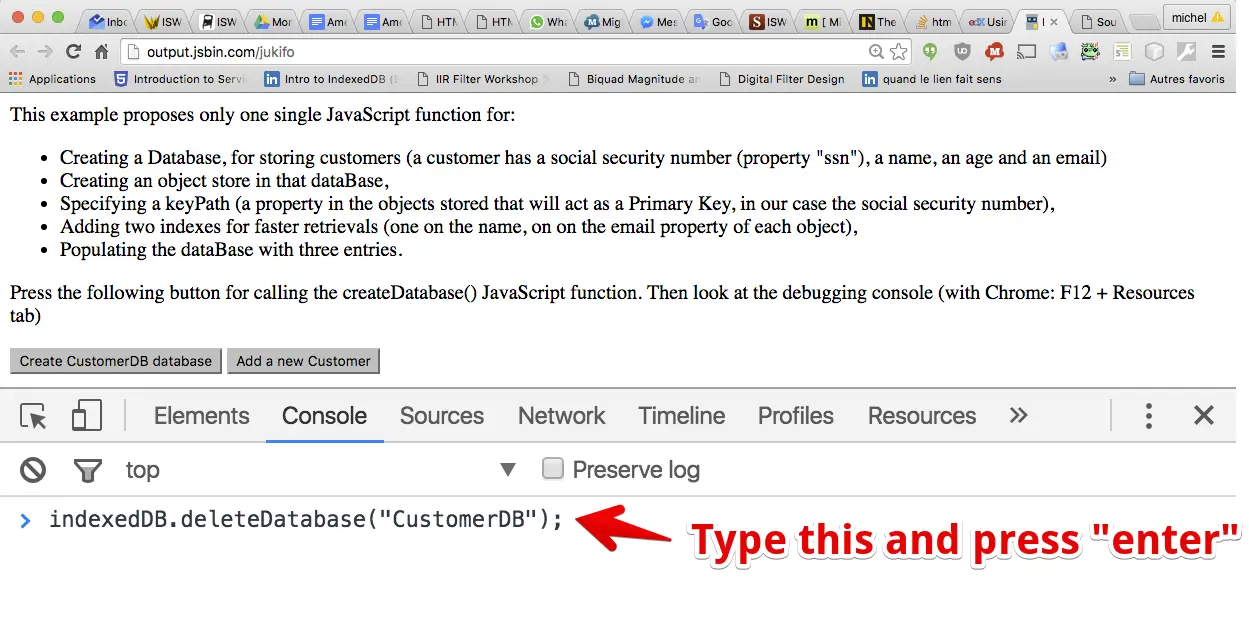

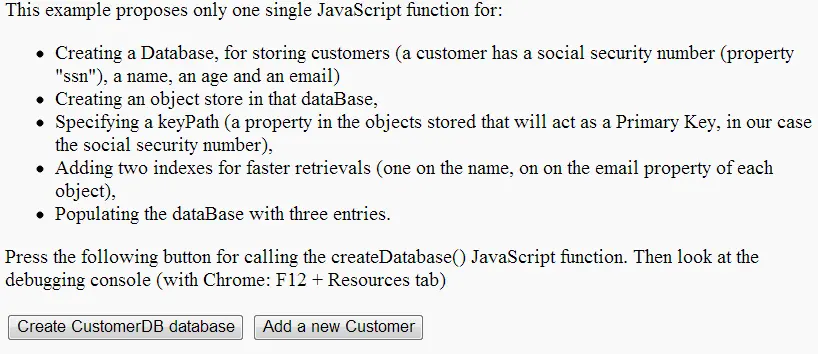

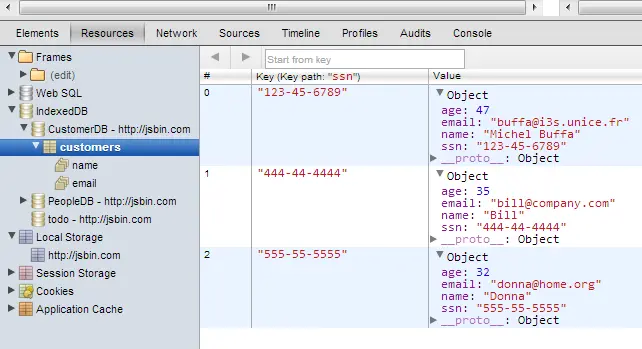

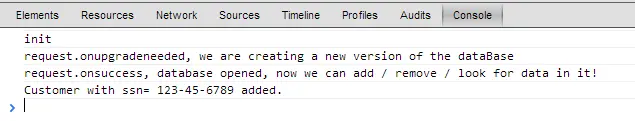

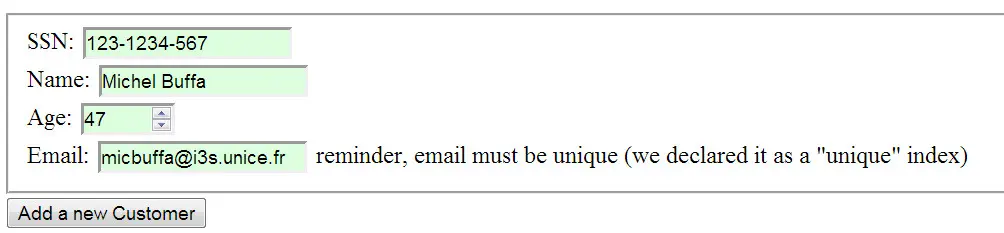

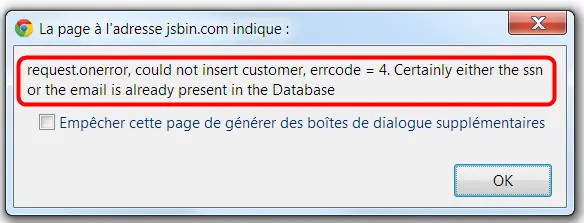

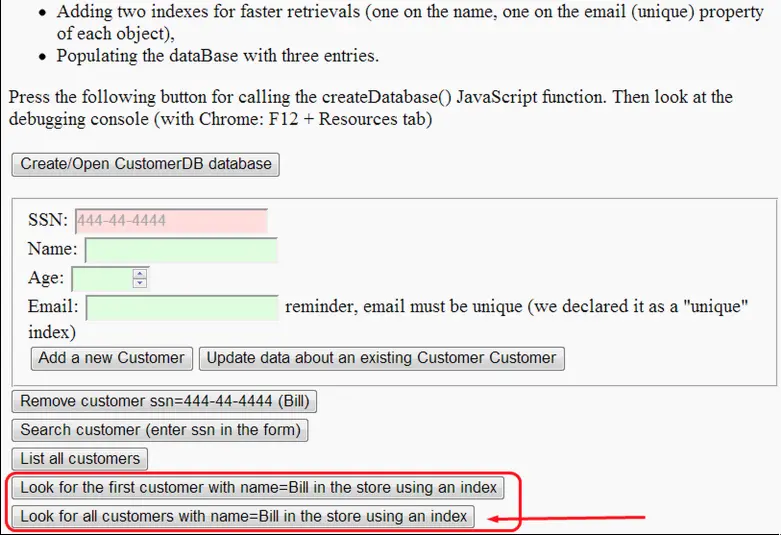

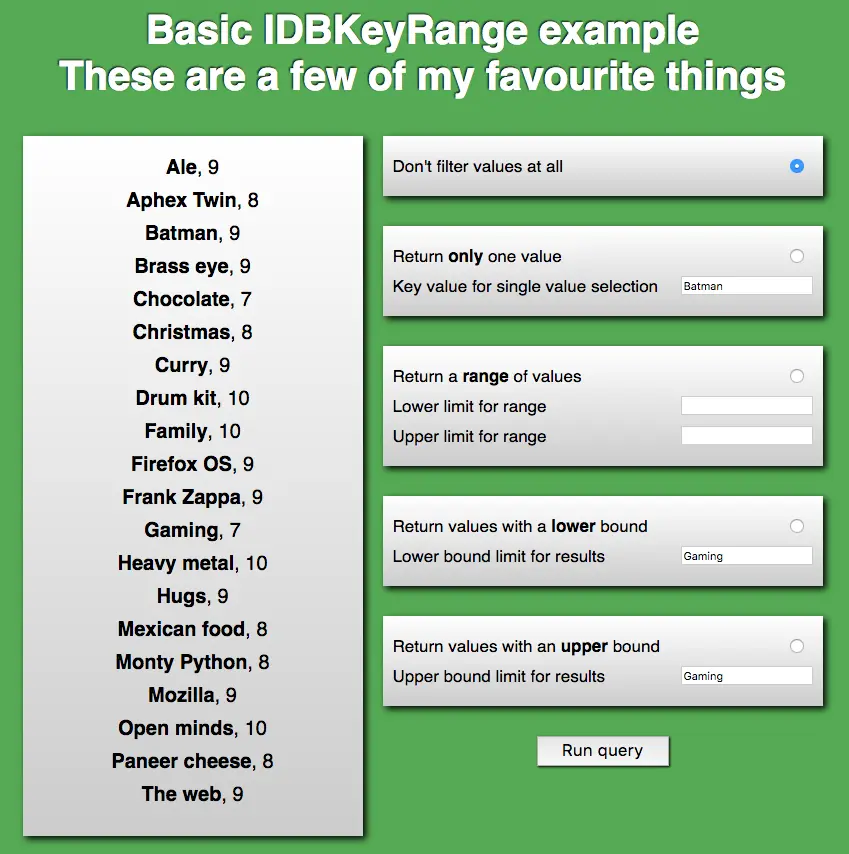

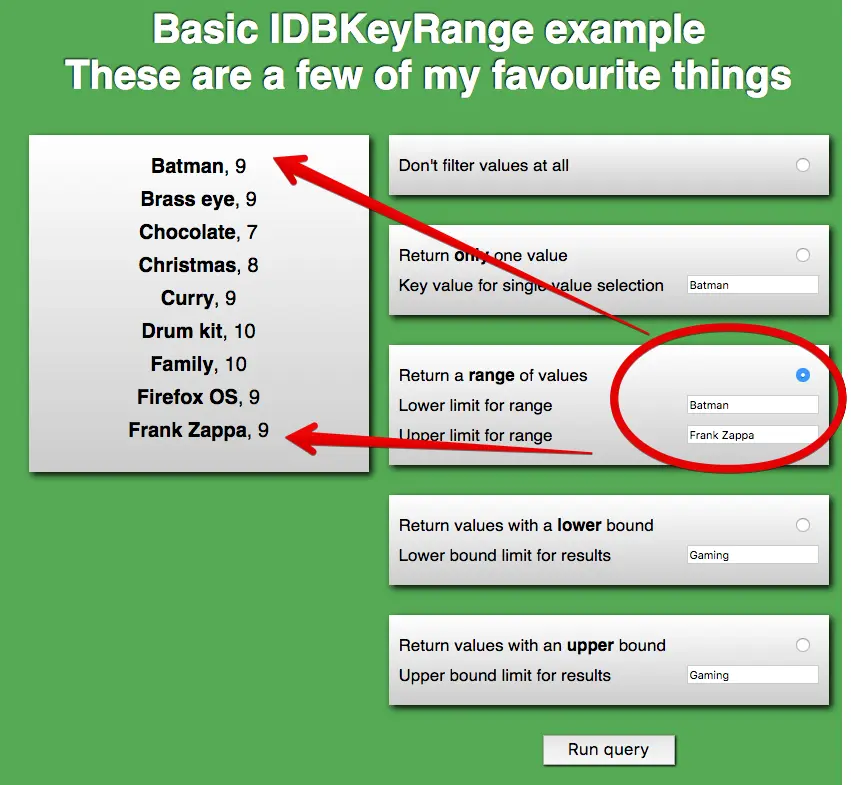

3.6. IndexedDB

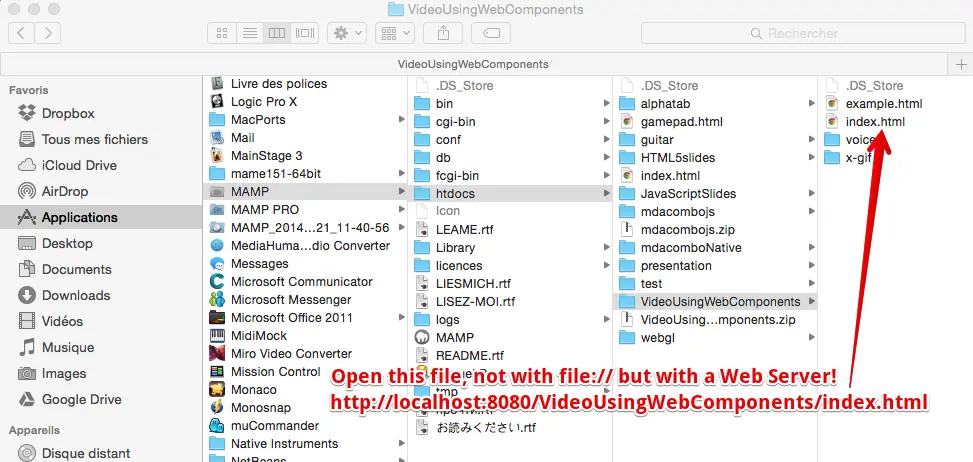

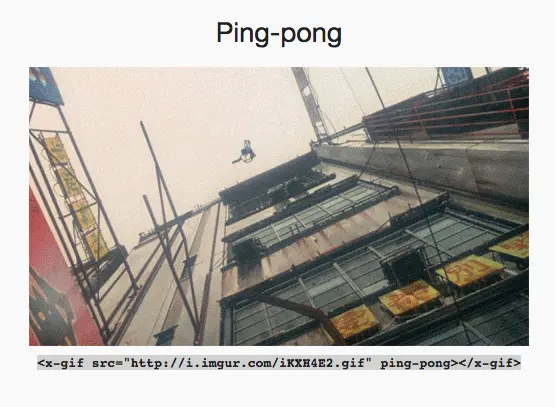

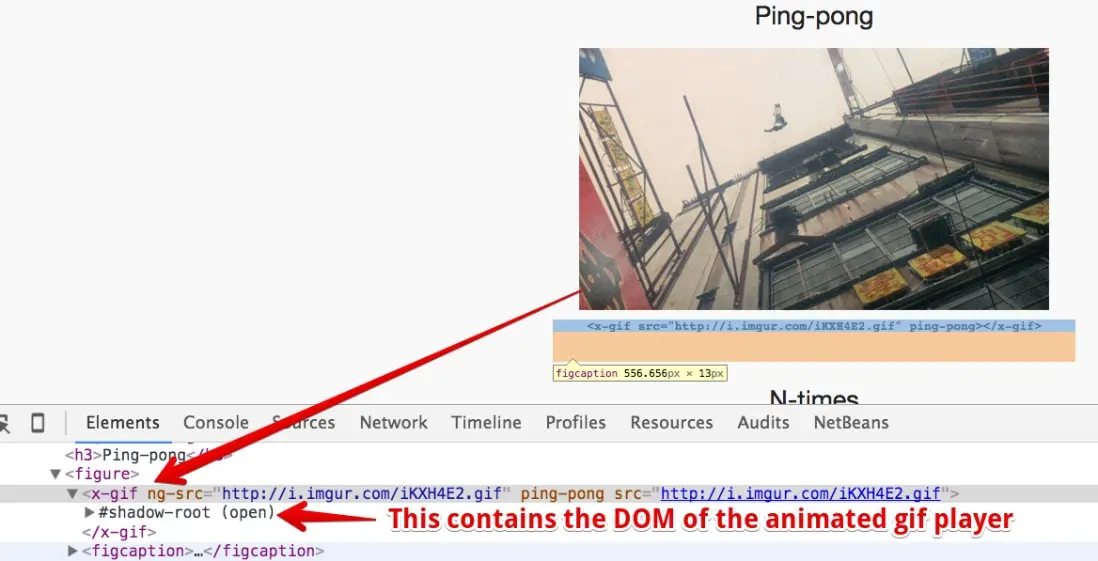

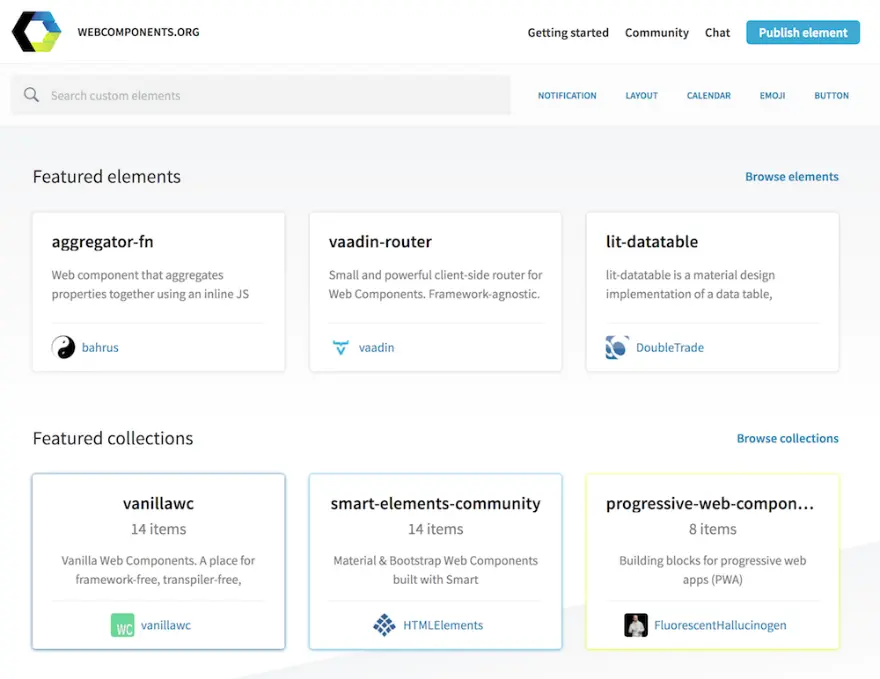

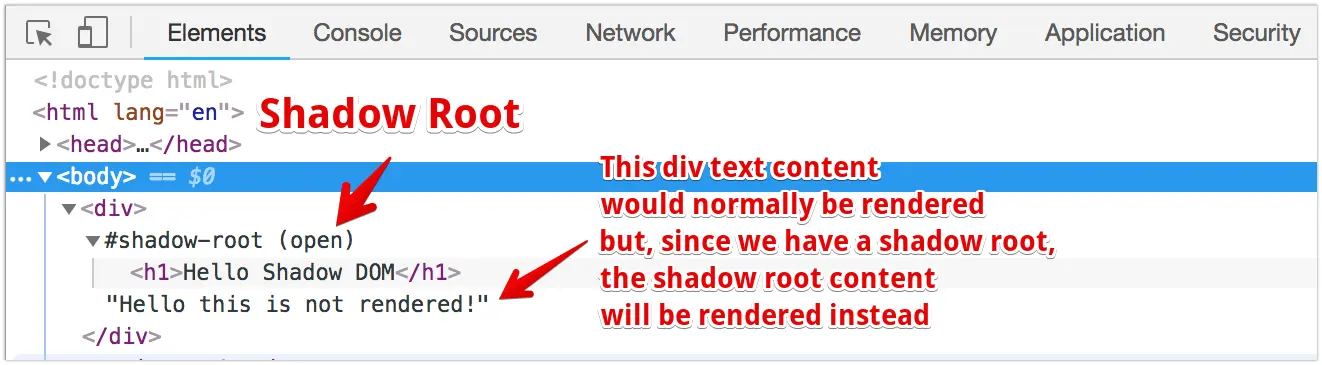

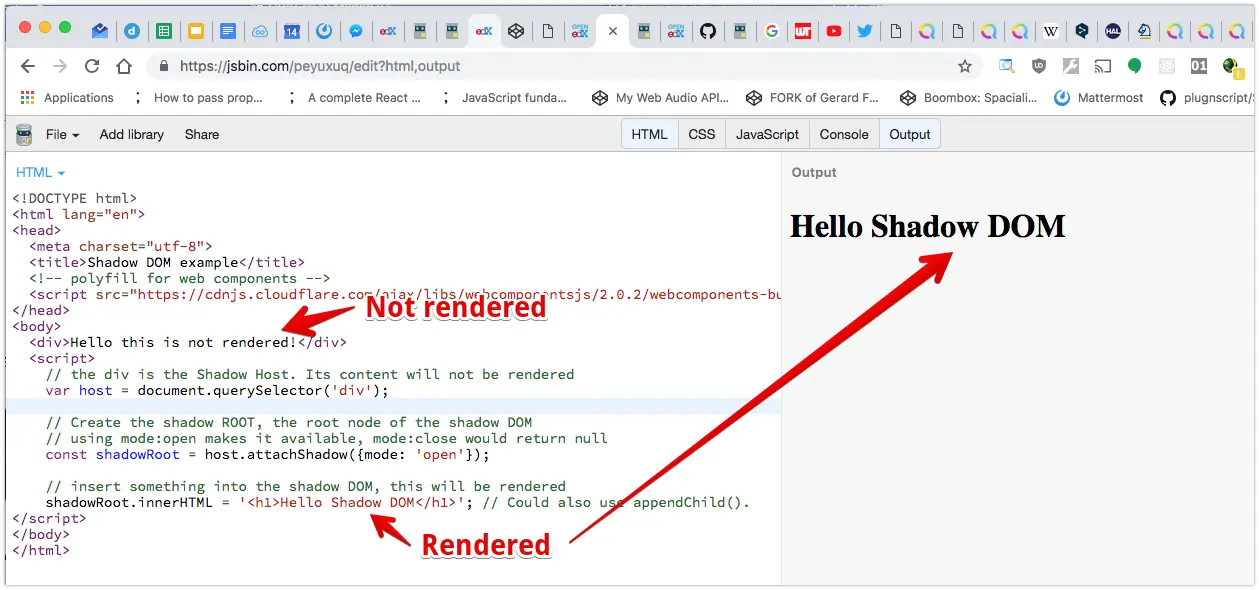

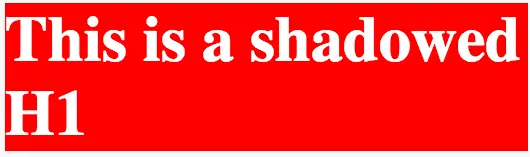

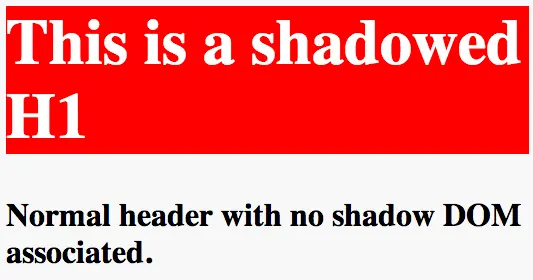

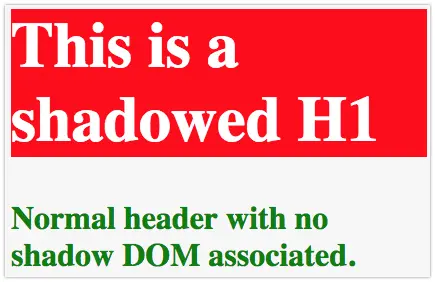

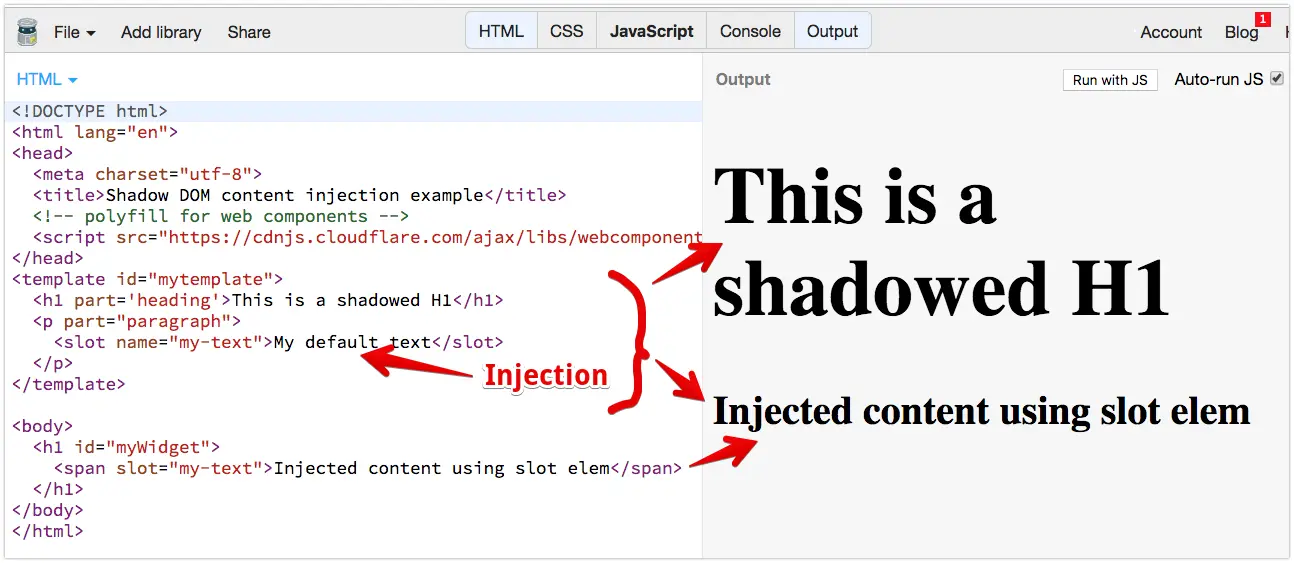

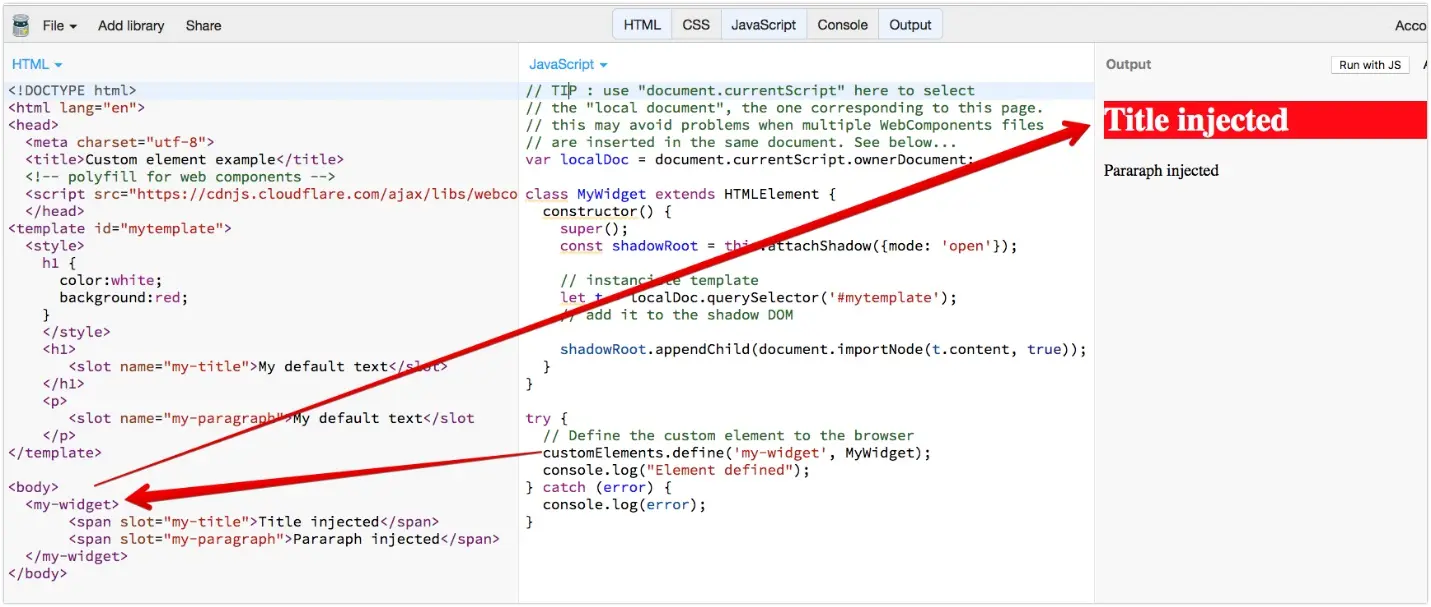

4.1.Introduction - Web Components & Other HTML5 APIs

4.2.Web Components

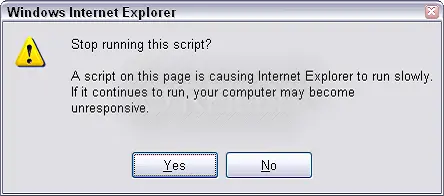

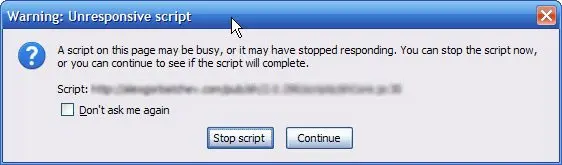

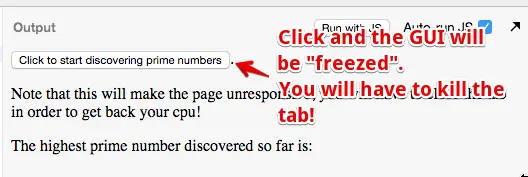

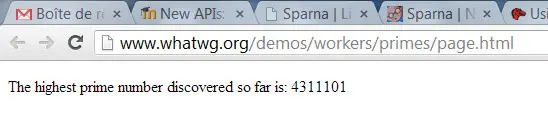

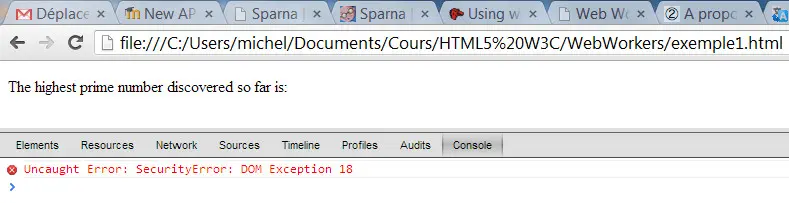

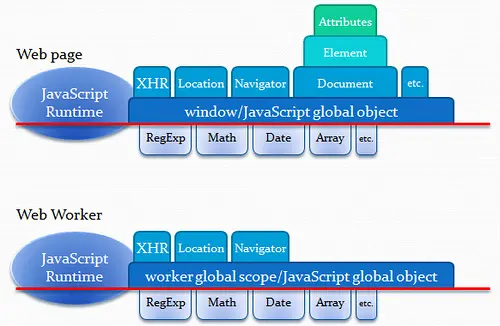

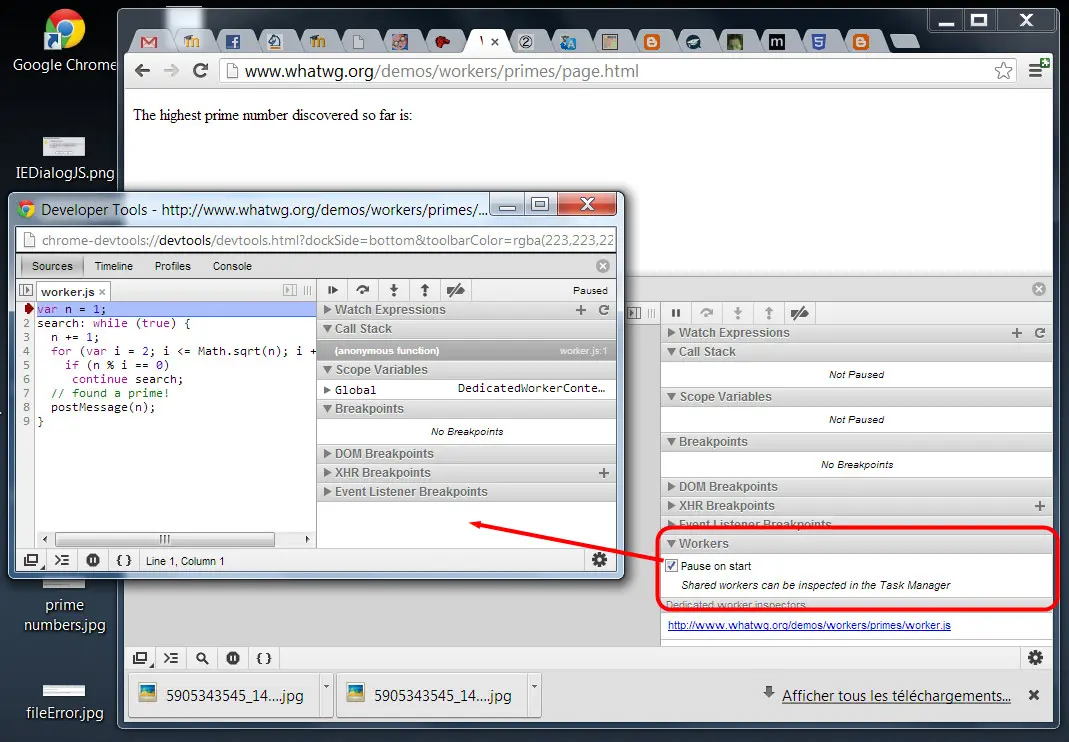

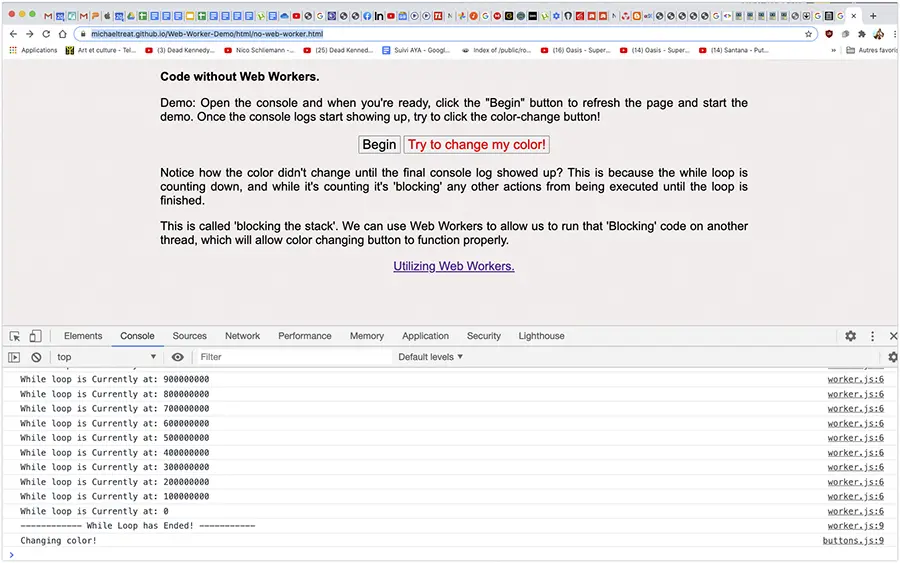

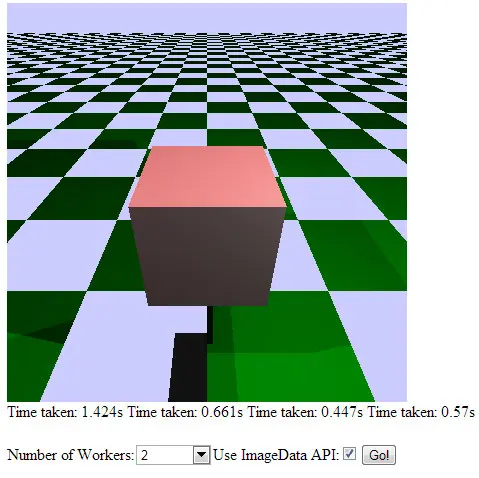

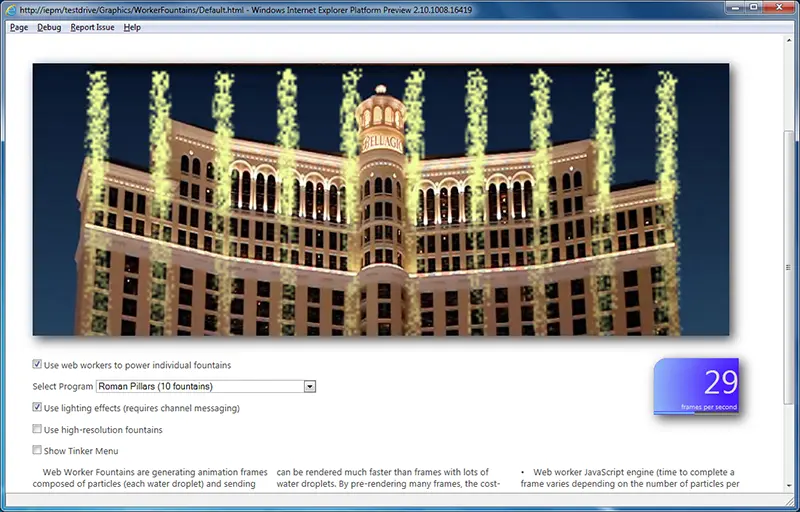

4.3.Web Workers

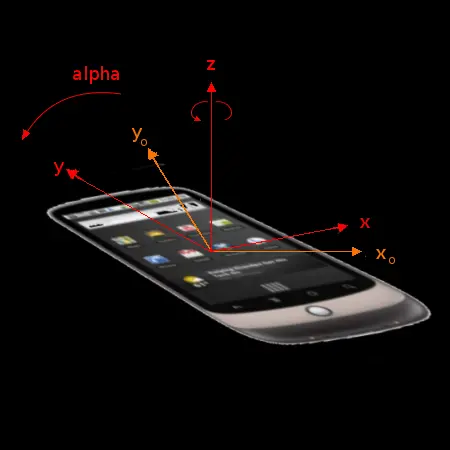

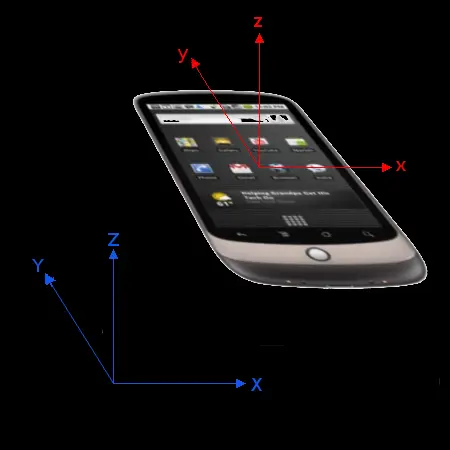

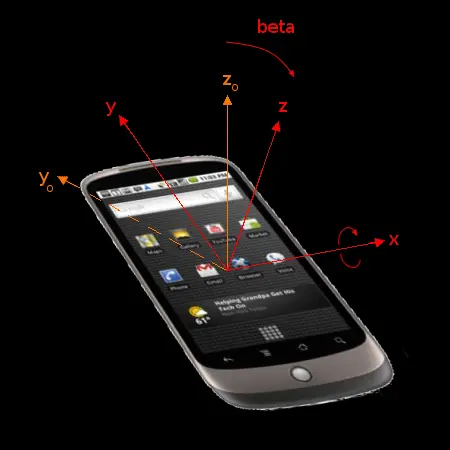

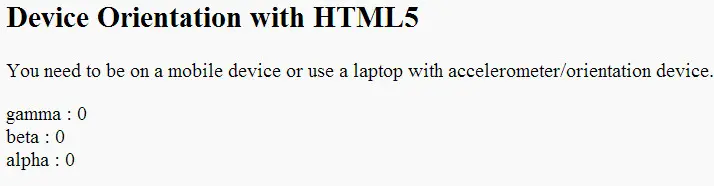

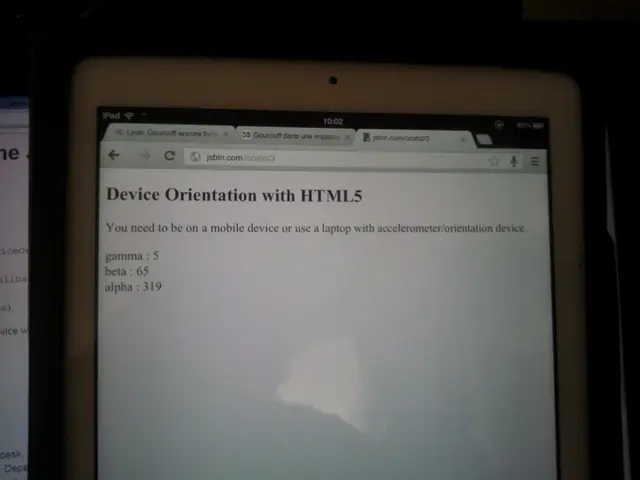

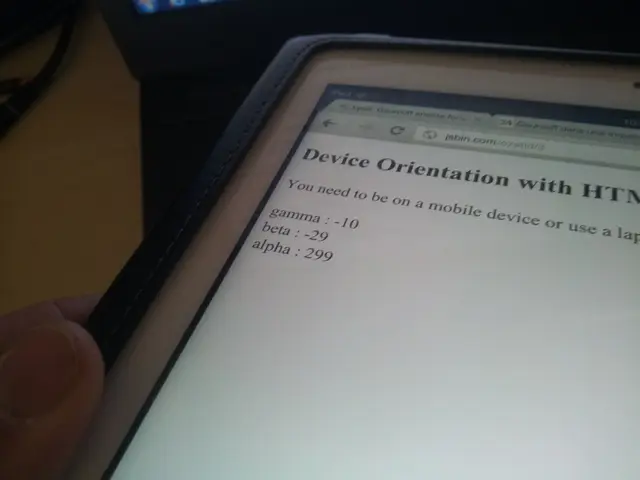

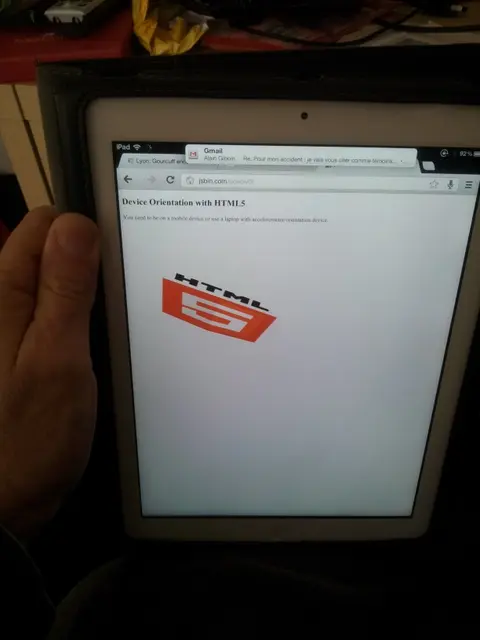

4.4.The Orientation and Device Motion APIs

W3Cx-4of5-HTML5.2x – Apps and Games HTML5.2x Apps and Games - git

During this course, you will discover advanced HTML5 techniques to help you develop innovative projects and applications. Please try to work on one of the many proposed optional projects, to be found at the end of each section. Remember that if you are not comfortable with JavaScript, no worries. Just start creating from one of the provided examples or follow our JavaScript Introduction course. And most of all, have fun!

This module also gives you a flavor of other HTML5 APIs such as the Orientation API which is useful for monitoring and controlling games and other activities; and Web Workers which introduce the power of parallel processing to Web apps.

This HTML5 Apps and Games course is part of the Front-End Web Developer” (FEWD) Professional Certificate program. To get this FEWD certificate, you will need to successfully pass all 5 courses that compose that program. Find out more on w3cx.org!

If you already have a verified certificate in one or more of these courses, you do NOT need to re-take that course.

This course is one of the courses composing the “Front-End Web Developer”

You will dive into advanced techniques, combining HTML5, CSS and JavaScript, to create your own HTML5 app and/or game.

Not surprisingly, it would be helpful to have a browser (short for “Web Browser”) installed so that you can see the end result of your source code. Most common browsers are Edge (and IE), Firefox, Chrome, Safari, etc.

Look for the history of Web browsers (on Wikipedia). An interesting resource is the market and platform market share (updated regularly).

While any text editor, like NotePad or TextEdit, can be used to create Web pages, they don’t necessarily offer a lot of help towards that end. Some others offer more facilities for error checking, syntax coloring and saving some typing by filling things out for you. Check the following sample:

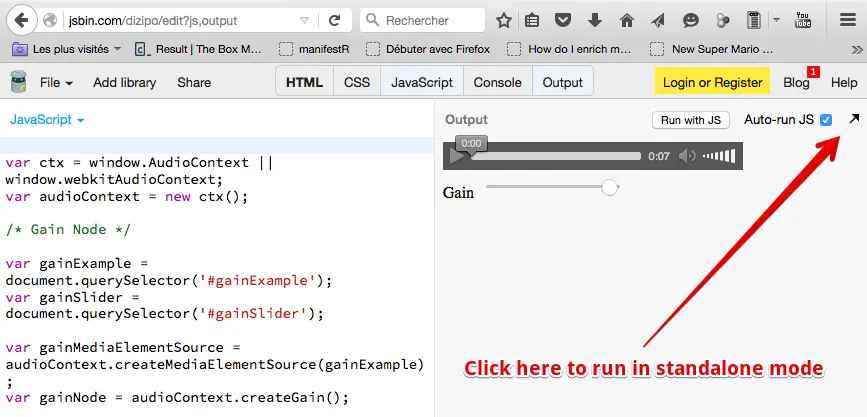

To help you practice during the whole duration of the course, you will use the following online editor tools. Pretty much all the course’s examples will actually use these.

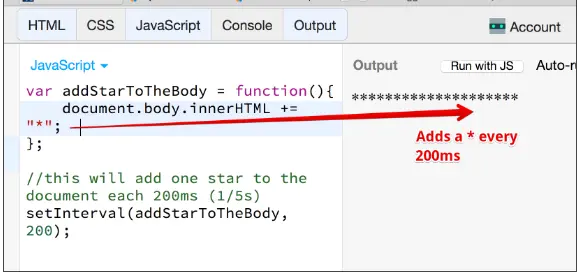

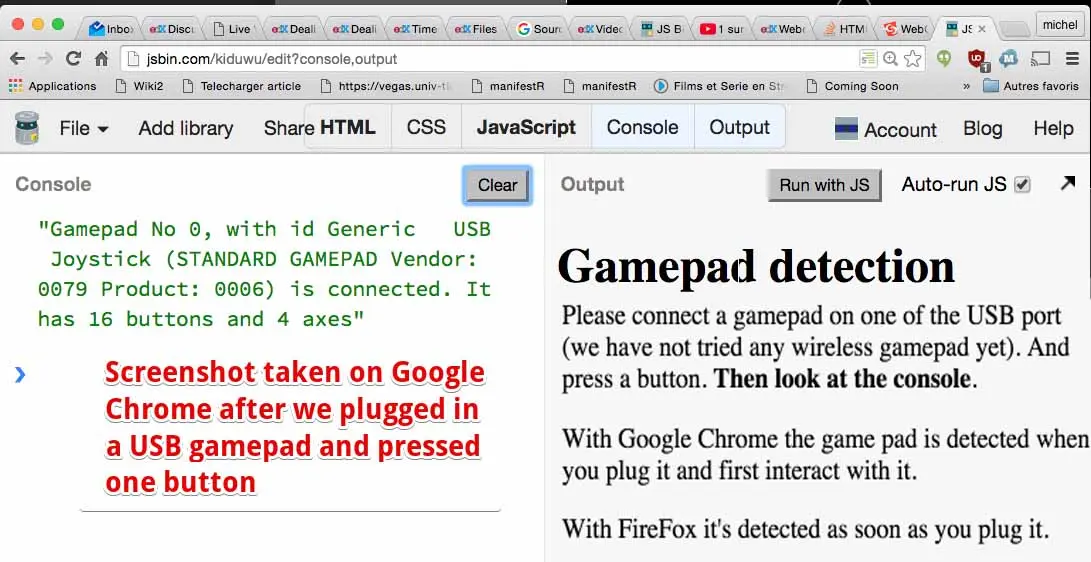

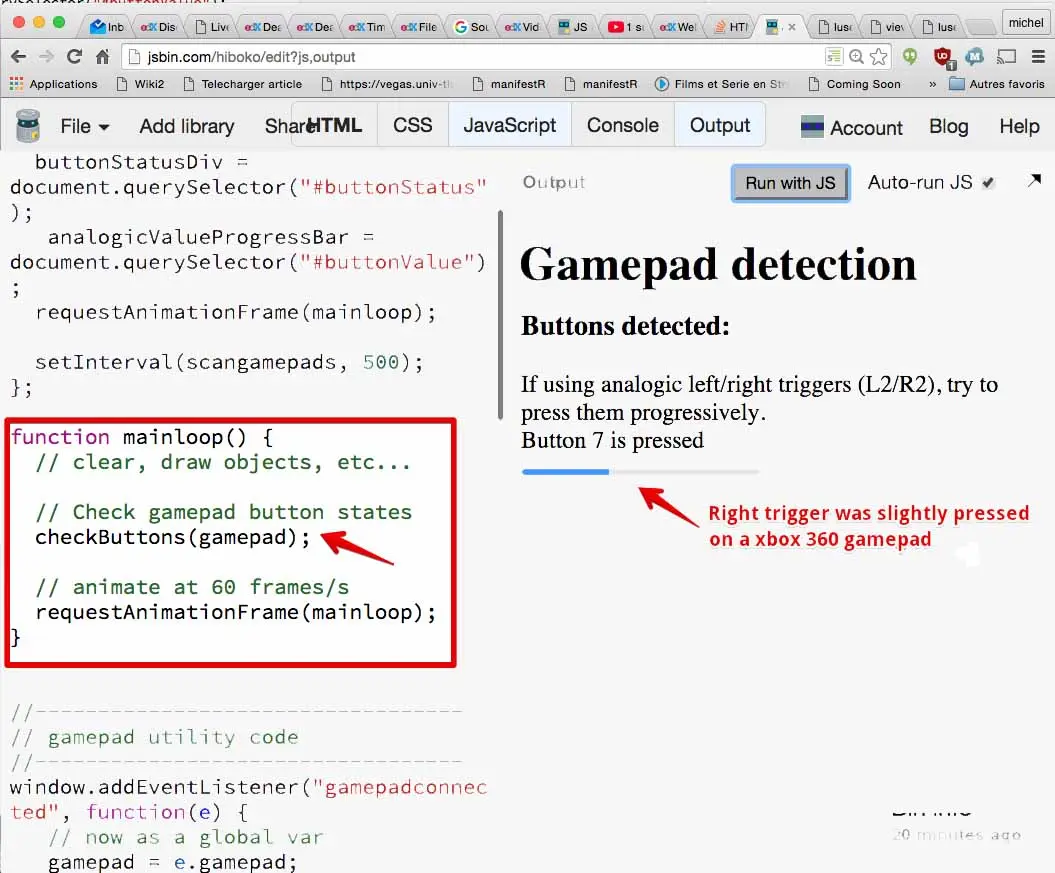

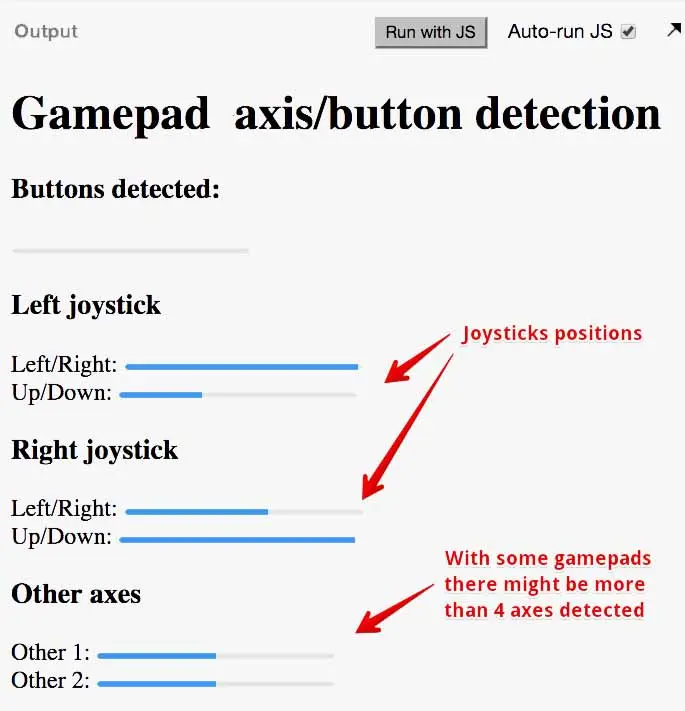

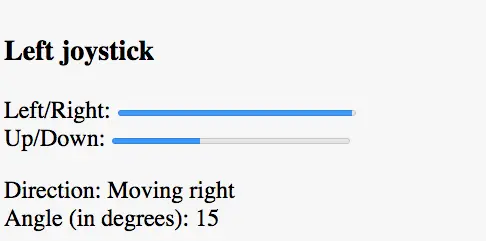

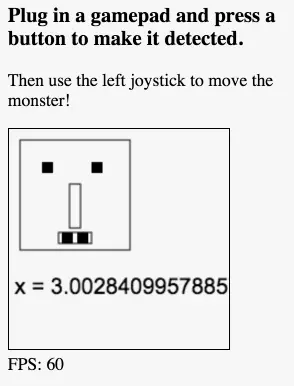

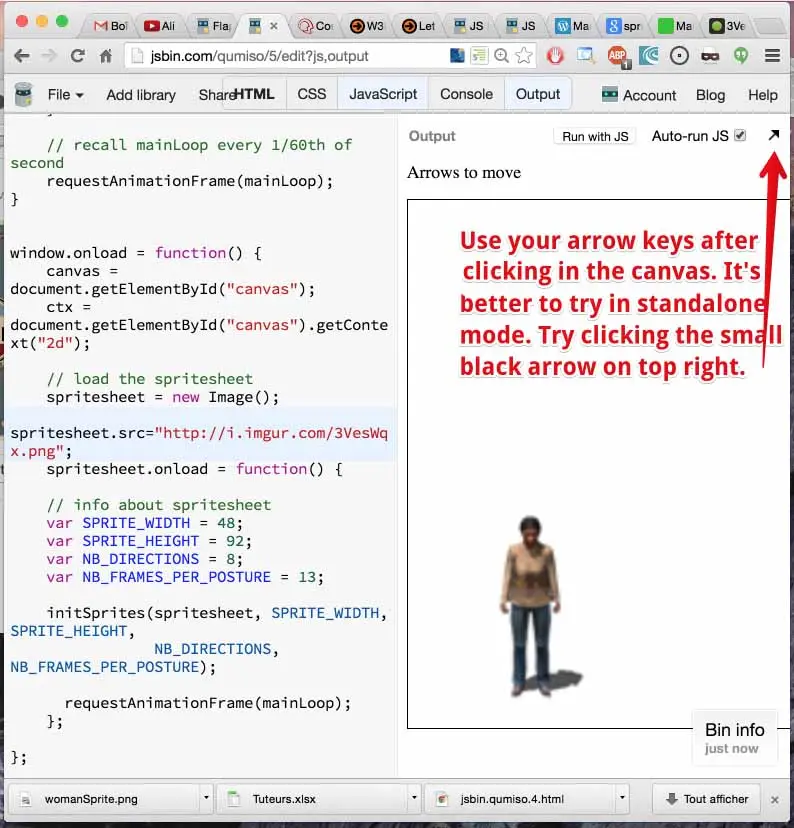

JS Bin is an open source collaborative Web development debugging tool. This tool is really simple, just open the link to the provided examples, look at the code, look at the result, etc. And you can modify the examples as you like, you can also modify / clone / save / share them.

Tutorials can be found on the Web (such as this one) or on YouTube. Keep in mind that it’s always better to be logged in (it’s free) if you do not want to lose your contributions/personal work.

CodePen is an HTML, CSS, and JavaScript code editor that previews/showcases your code bits in your browser. It helps with cross-device testing, real-time remote pair programming and teaching.

This is a great service to get you started quickly as it doesn’t require you to download anything and you can access it, along with your saved projects from any Web browser. Here’s an article which will be of-interest if you use CodePen: Things you can do with CodePen [Brent Miller, February 6, 2019].

There are many other handy tools such as JSFiddle, and Dabblet (Lea Verou’s tool that we will use extensively in a future CSS course). Please share your favorite tool on the discussion forum, and explain why! Share also your own code contributions, such as a nice canvas animation, a great looking HTML5 form, etc. Sharing them using JS Bin, or similar tools, would be really appreciated.

For over 20 years, the W3C has been developing and hosting [free and open source tools] used every day by millions of Web developers and Web designers. All the tools listed below are Web-based, and are available as downloadable sources or as free services on the W3C Developers tools site.

The W3C validator checks the markup validity of various Web document formats, such as HTML.

The CSS validator checks Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) and (X)HTML documents that use CSS stylesheets.

Unicorn is W3C’s unified validator, which helps people improve the quality of their Web pages by performing a variety of checks. Unicorn gathers the results of the popular HTML and CSS validators, as well as other useful services, such s RSS/Atom feeds and http headers.

The W3C Link Checker looks for issues in links, anchors and referenced objects in a Web page, CSS style sheet, or recursively on a whole Web site. For best results, it is recommended to first ensure that the documents checked use valid W3 Validator and CSS HTML Markup.

The W3C Internationalization Checker provides information about various internationalization-related aspects of your page, including the HTTP headers that affect it. It also reports a number of issues and offers advice about how to resolve them.

The W3C cheatsheet provides quick access to useful information from a variety of specifications published by W3C. It aims at giving in a very compact and mobile- friendly format a compilation of useful knowledge extracted from W3C specifications, completed by summaries of guidelines developed at W3C, in particular Web accessibility guidelines, the Mobile Web Best Practices, and a number of internationalization tips.

Its main feature is a lookup search box, where one can start typing a keyword and get a list of matching properties/elements/attributes/functions in the above-mentioned specifications, and further details on those when selecting the one of interest.

The W3C cheatsheet is only available as a pure Web application.

The term browser compatibility refers to the ability of a given Web site to appear fully functional on the browsers available in the market.

The most powerful aspect of the Web is what makes it so challenging to build for: its universality. When you create a Web site, you’re writing code that needs to be understood by many different browsers on different devices and operating systems!

To make the Web evolve in a sane and sustainable way for both users and developers, browser vendors work together to standardize new features, whether it’s a new HTML element, CSS property, or JavaScript API. But different vendors have different priorities, resources, and release cycles — so it’s very unlikely that a new feature will land on all the major browsers at once. As a Web developer, this is something you must consider if you’re relying on a feature to build your site.

We are then providing references to the browser support of HTML5 features presented in this course using 2 resources: Can I Use and Mozilla Developer Network (MDN) Web Docs.

Can I Use provides up-to-date tables for support of front-end Web technologies on desktop and mobile Web browsers. Below is a snapshot of what information is given by CanIUse when searching for “CSS3 colors”.

To help developers make these decisions consciously rather than accidentally, MDN Web Docs provides browser compatibility tables in its documentation pages, so that when looking up a feature you’re considering for your project, you know exactly which browsers will support it.

Most of the technologies you use when developing Web applications and Web sites are designed and standardized in W3C in a completely open and transparent process.

In fact, all W3C specifications are developed in public GitHub repositories, so if you are familiar with GitHub, you already know how to contribute to W3C specifications! This is all about raising issues (with feedback and suggestions) and/or bringing pull requests to fix identified issues.

Contributing to this standardization process might be a bit scary or hard to approach at first, but understanding at a deeper level how these technologies are built is a great way to build your expertise.

If you’re looking to an easy way to dive into this standardization processes, check out which issues in the W3C GitHub repositories have been marked as “good first issue” and see if you find anything where you think you would be ready to help.

Shape the future

Another approach is to go and bring feedback on ideas for future technologies: the W3C Web Platform Community Incubator Group was built as an easy place to get started to provide feedback on new proposals or bring brand-new proposals for consideration.

Happy Web building!

As steward of global Web standards, W3C’s mission is to safeguard the openness, accessibility, and freedom of the World Wide Web from a technical perspective.

W3C’s primary activity is to develop protocols and guidelines that ensure long-term growth for the Web. The widely adopted Web standards define key parts of what actually makes the World Wide Web work.

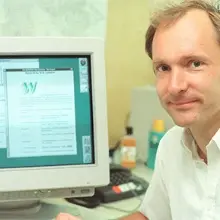

In March 1989, while at CERN, Sir Tim Berners-Lee wrote “ Information Management: A Proposal” outlining the World Wide Web. Tim’s memo was about to revolutionize communication around the globe. He then created the first Web browser, server, and Web page. He wrote the first specifications for URLs, HTTP, and HTML.

Tim Berners-Lee at his desk in CERN, 1994

In October 1994, Tim Berners-Lee founded the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Laboratory for Computer Science [MIT/LCS] in collaboration with CERN, where the Web originated (see information on the original CERN Server), with support from DARPA and the European Commission.

In April 1995, Inria became the first European W3C host, followed by Keio University of Japan (Shonan Fujisawa Campus) in Asia in 1996. In 2003, ERCIM took over the role of European W3C Host from Inria. In 2013, W3C announced Beihang University as the fourth Host.

As of August 2020, W3C:

Committed to core values of an open Web that promotes innovation, neutrality, and interoperability, W3C and its community are setting the vision and standards for the Web, ensuring the building blocks of the Web are open, accessible, secure, international and have been developed via the collaboration of global technical experts.

You find below three examples (and checks!) to help you to ensure that your Web page works for people around the world, and to make it work differently for different cultures, where needed. Let’s meet the words ‘charset’ and ‘lang’, soon to become your favorite markup ;)

A character encoding declaration is vital to ensure that the text in your page is recognized by browsers around the world, and not garbled. You will learn more about what this is, and how to use it as you work through the course. For now, just ensure that it’s always there.

Check #1: There is a character encoding declaration near the start of your source code, and its value is UTF-8.

<head> <meta charset="utf-8"/> ... </head>

For a wide variety of reasons, it’s important for a browser to know what language your page is written in, including font selection, text-to-speech conversion, spell-checking, hyphenation and automated line breaking, text transforms, automated translation, and more. You should always indicate the primary language of your page in the <html> tag. Again you will learn how to do this during the course. You will also learn how to change the language, where necessary, for parts of your document that are in a different language.

Check #2: The HTML tag has a lang attribute which correctly indicates the language of your content.

This example below indicates that the page is in French.

<!doctype html> <html lang="fr"> <head> ...

People around the world don’t always understand cultural references that you are familiar with, for example the concept of a ‘home run’ in baseball, or a particular type of food. You should be careful when using examples to illustrate ideas. Also, people in other cultures don’t necessarily identify with pictures that you would recognize, for example, hand gestures can have quite unexpected meanings in other parts of the world, and photos of people in a group may not be representative of populations elsewhere. When creating forms for capturing personal details, you will quickly find that your assumptions about how personal names and addresses work are very different from those of people from other cultures.

Check #3: If your content will be seen by people from diverse cultures, check that your cultural references will be recognized and that there is no inappropriate cultural bias.

Don’t worry!

The following 7 quick tips summarize some important concepts of international Web design. They will become more meaningful as you work through the course, so come back and review this page at the end.

You will find more quick tips on the Internationalization quick tips page. Remember that these tips do not constitute complete guidelines.

When you start creating Web pages, you can also run them through the W3C’s Internationalization Checker. If there are internationalization problems with your page, this checker explains what they are and what to do about it.

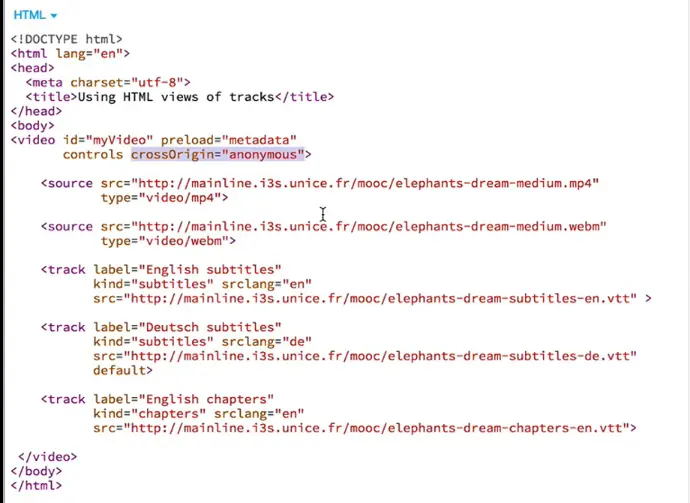

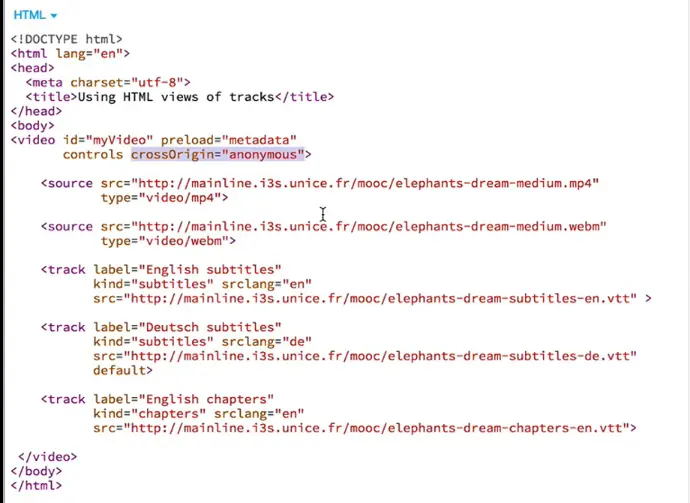

In the W3Cx HTML5 Coding Essentials and Best Practices course, we saw that <video> and <audio> elements can have <track> elements. A <track> can have a label, a kind (subtitles, captions, chapters, metadata, etc.), a language (srclang attribute), a source URL (src attribute), etc.

Here is a small example of a video with 3 different tracks (“……” masks the real URL here, as it is too long to fit in this page width!):

<video id="myVideo" preload="metadata" controls crossOrigin="anonymous">

<source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.mp4" type="video/mp4">

<source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.webm" type="video/webm">

<track label="English subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-en.vtt">

<track label="Deutsch subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="de"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-de.vtt" default>

<track label="English chapters" kind="chapters" srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-chapters-en.vtt">

</video>

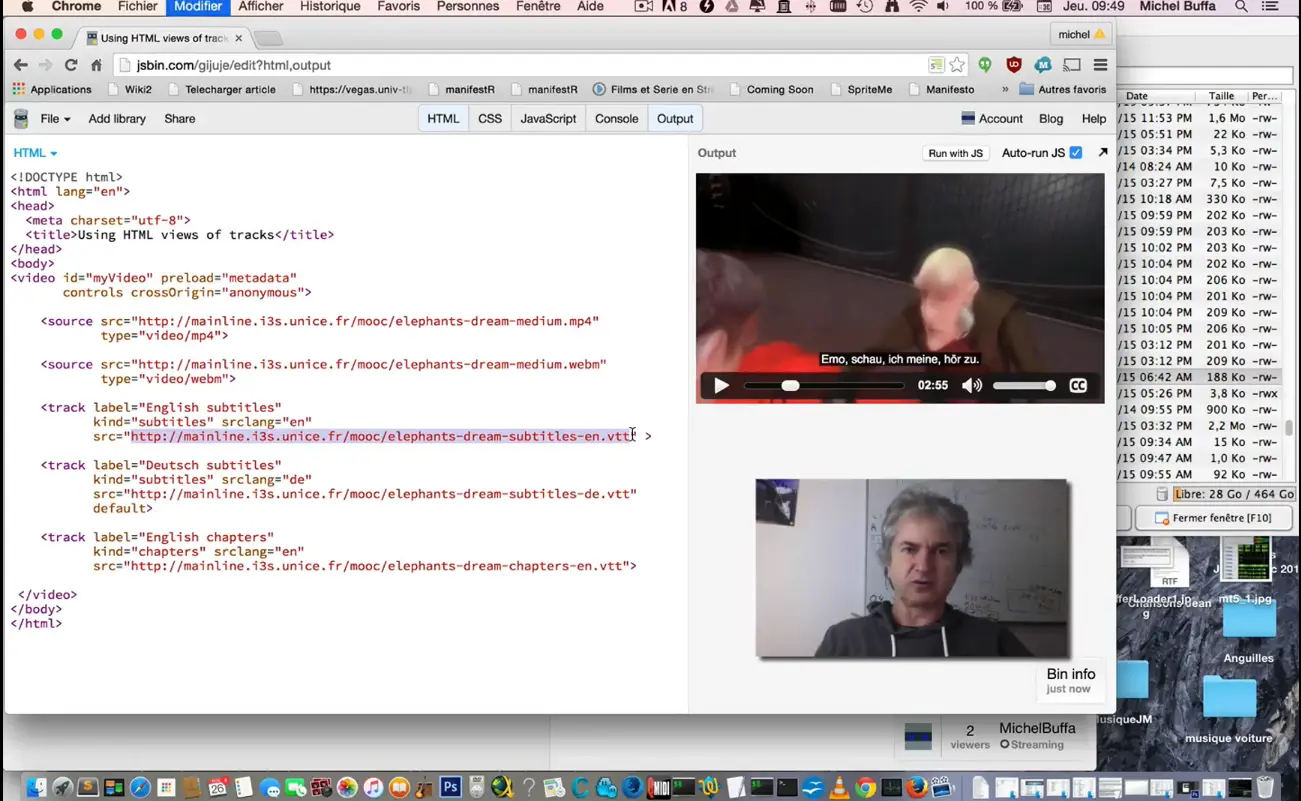

And here is how it renders in your current browser (please play the video and try to show/hide the subtitles/captions):

Notice that the support for multiple tracks may differ significantly from one browser to another, in particular if you are using old versions.

Here is a quick summary (as of May 2020).

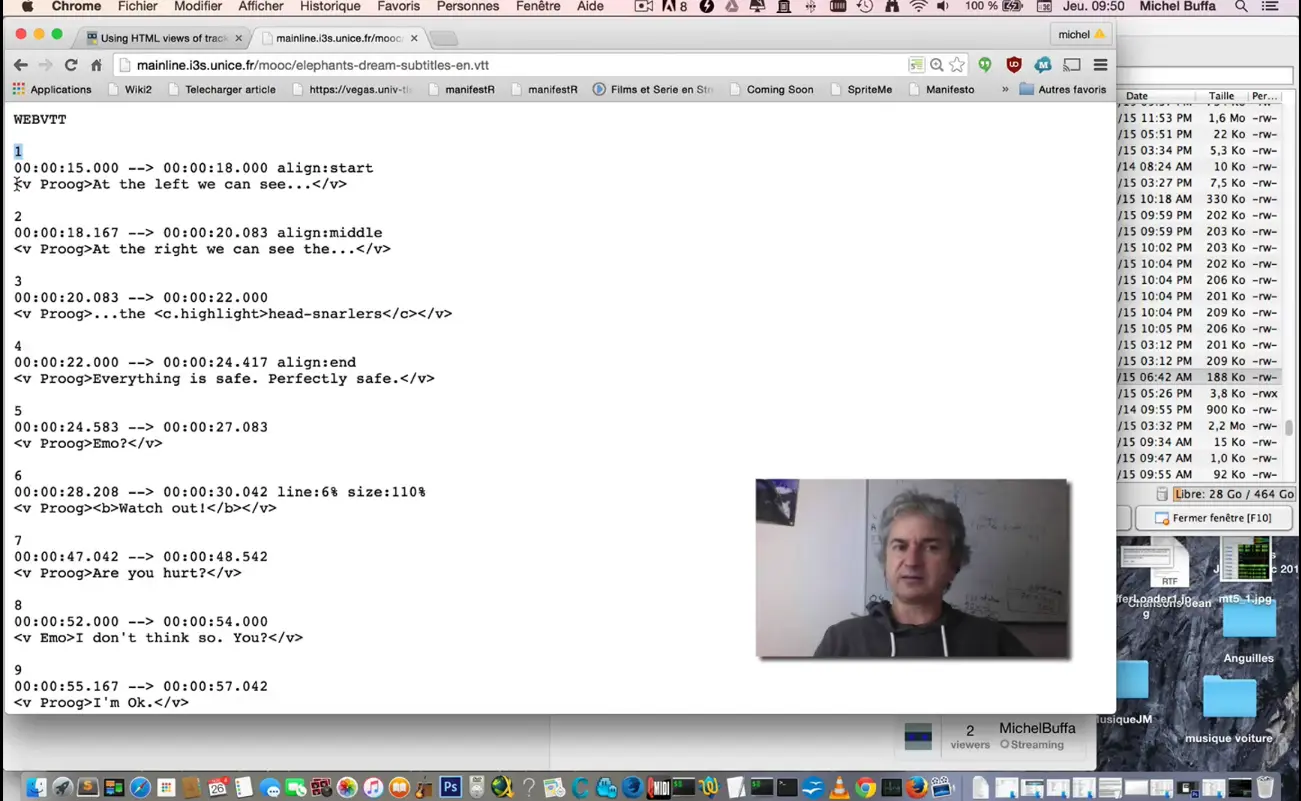

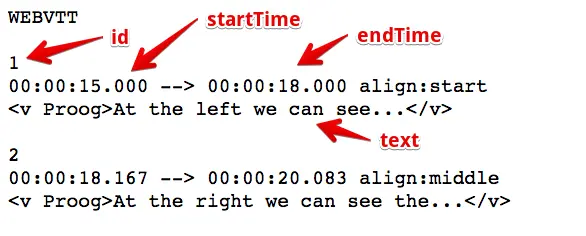

Also, there is a Timed Text Track API in the HTML5/HTML5.1 specification that enables us to manipulate <track> contents from JavaScript. Do you recall that text tracks are associated with WebVTT files? As a quick reminder, let’s look at a WebVTT file:

1 00:00:15.000 --> 00:00:18.000 align:start <v Proog>On the left we can see...</v> 2 00:00:18.167 --> 00:00:20.083 align:middle <v Proog>On the right we can see the...</v> 3 00:00:20.083 --> 00:00:22.000 <v Proog>...the <c.highlight>head-snarlers</c></v> 4 00:00:22.000 --> 00:00:24.417 align:end <v Proog>Everything is safe. Perfectly safe.</v>

The different time segments are called “cues” and each cue has an id (1, 2, 3 and 4 in the above example), a startTime and an endTime, and a text content that can contain HTML tags for styling (<b>, etc…) or be associated with a “voice” as in the above example. In this case, the text content is wrapped inside <v name_of_speaker>…</v> elements.

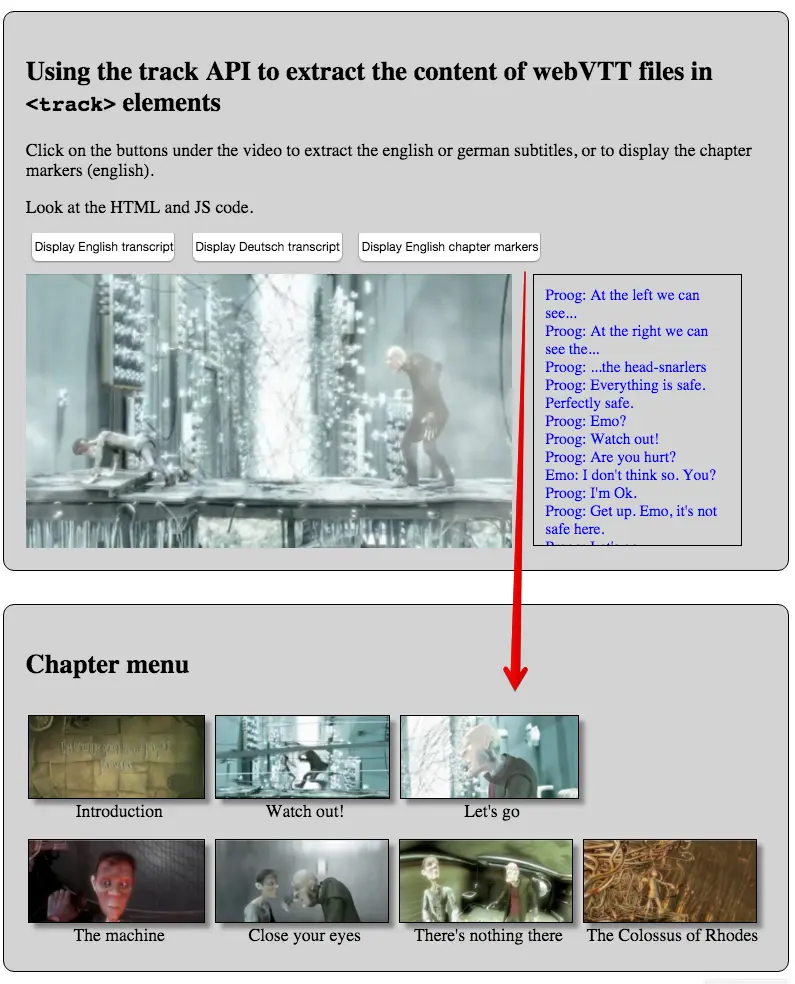

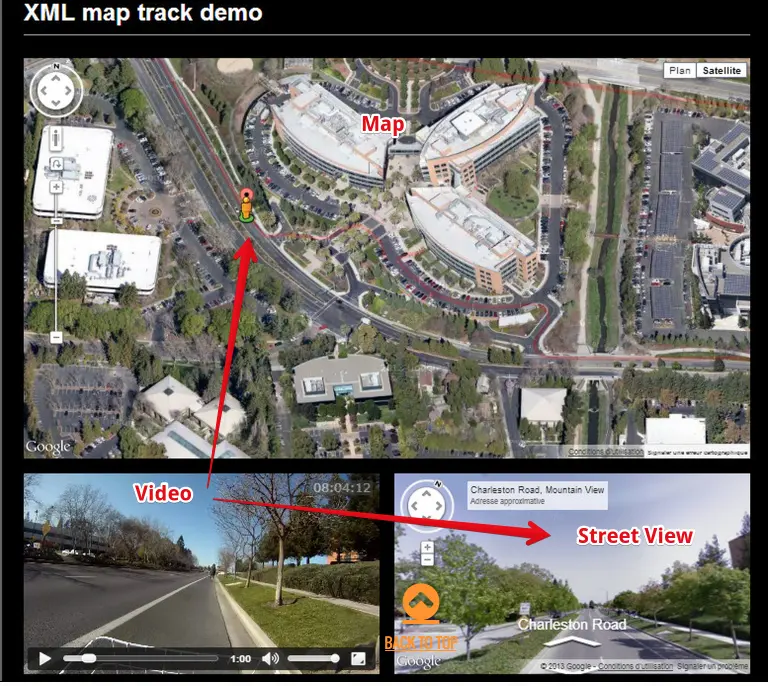

It’s now time to look at the JavaScript API for manipulating tracks, cues, and events associated with their life cycle. In the following lessons, we will look at different examples which use this API to implement missing features such as:

Hi! Welcome to Part 2 of the W3C HTML5 course. How about we start by looking at advanced HTML5 multimedia features?

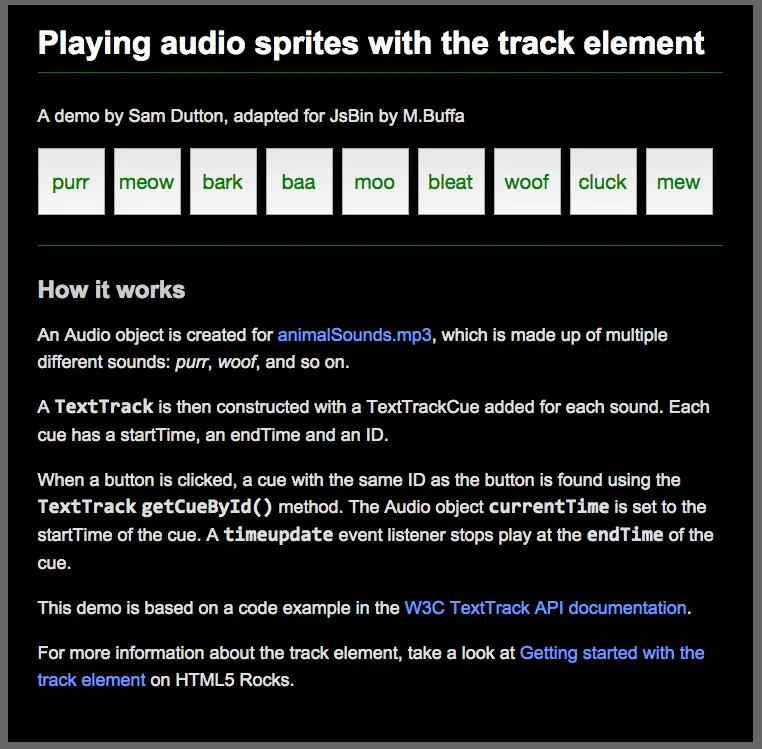

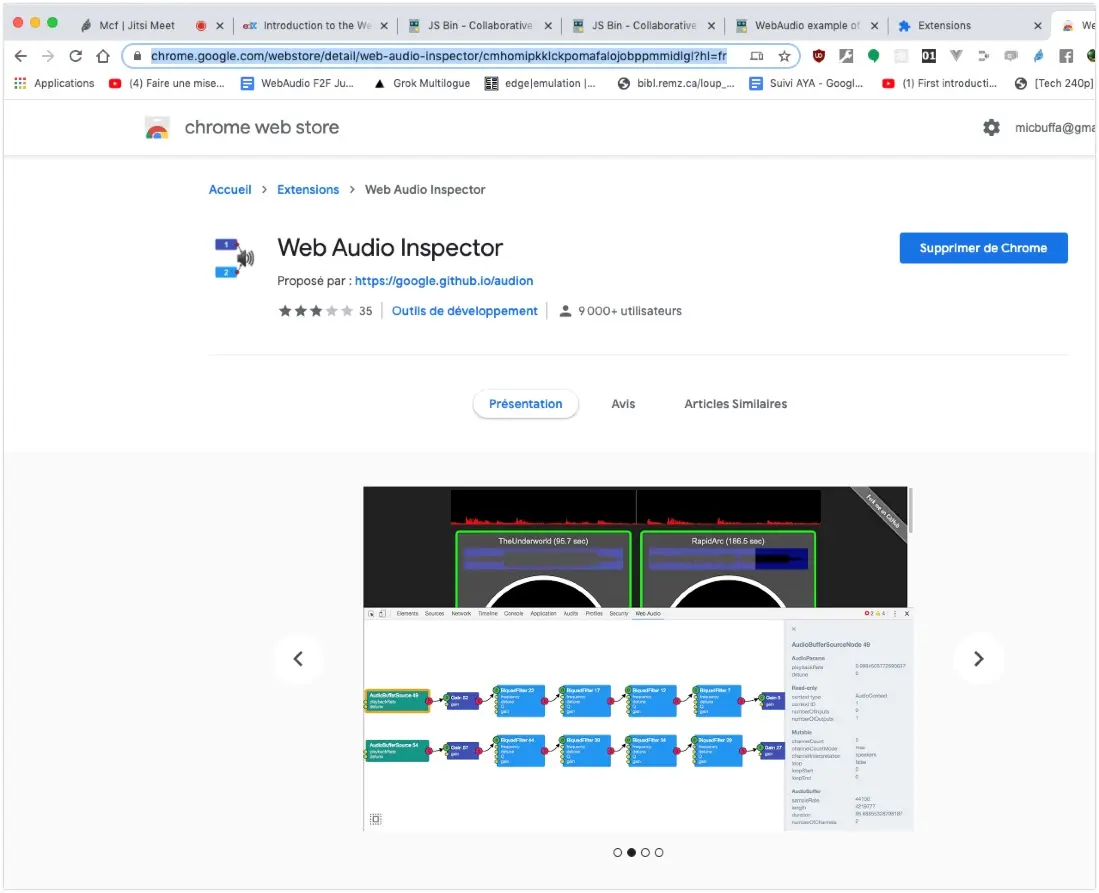

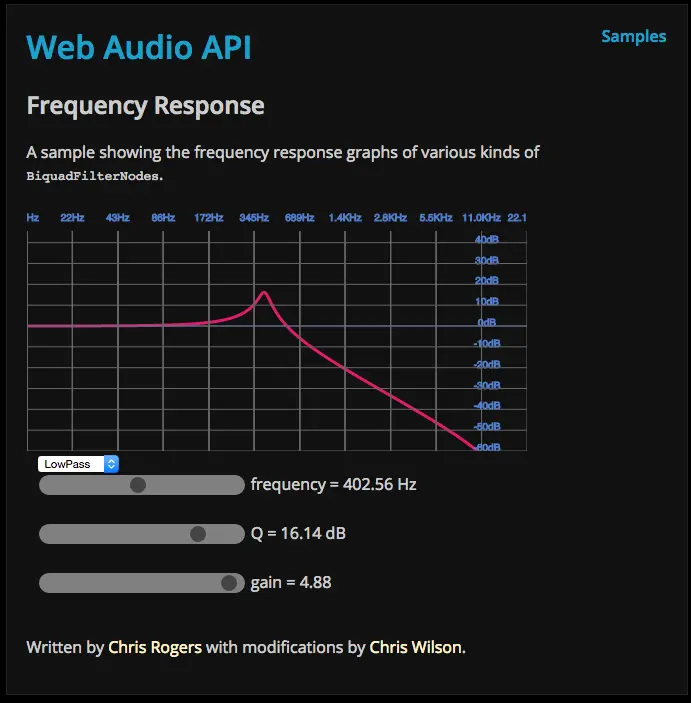

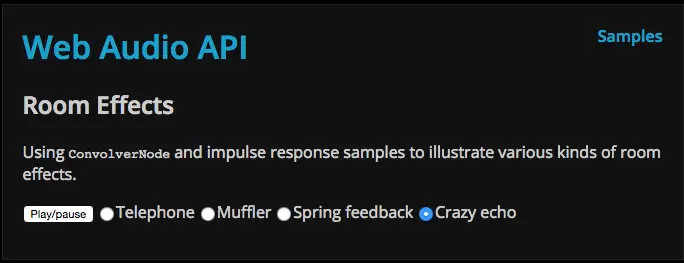

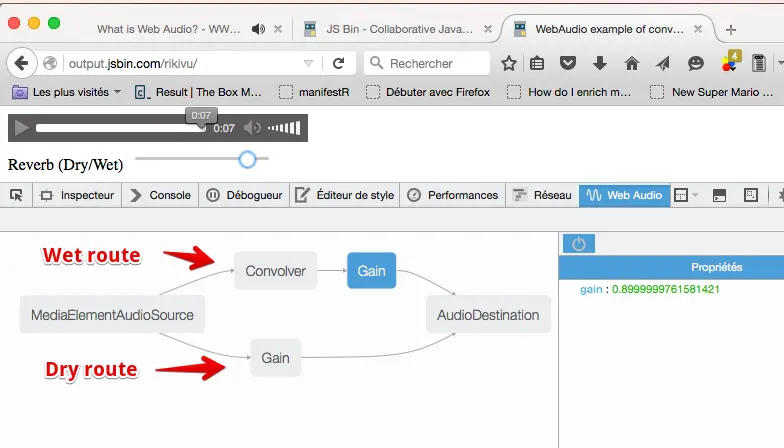

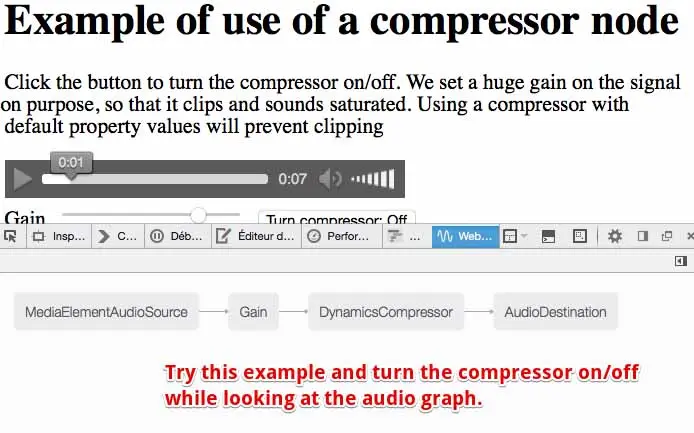

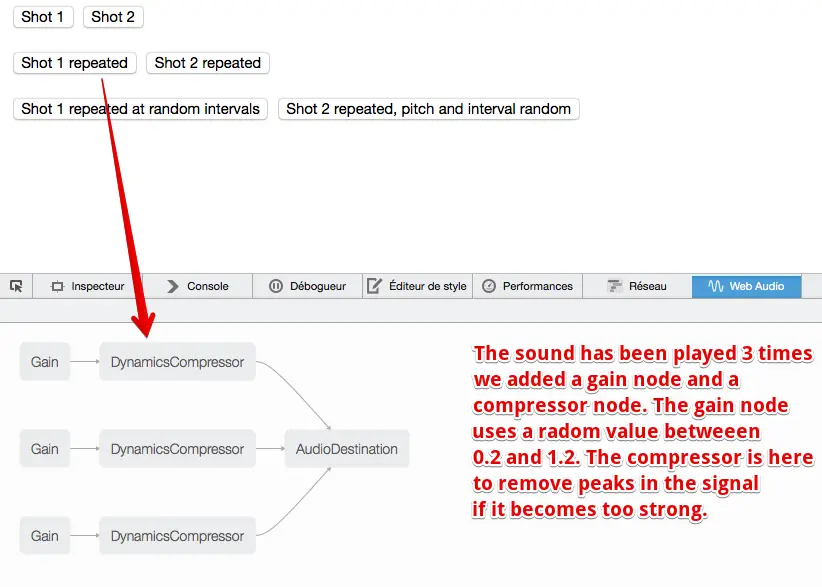

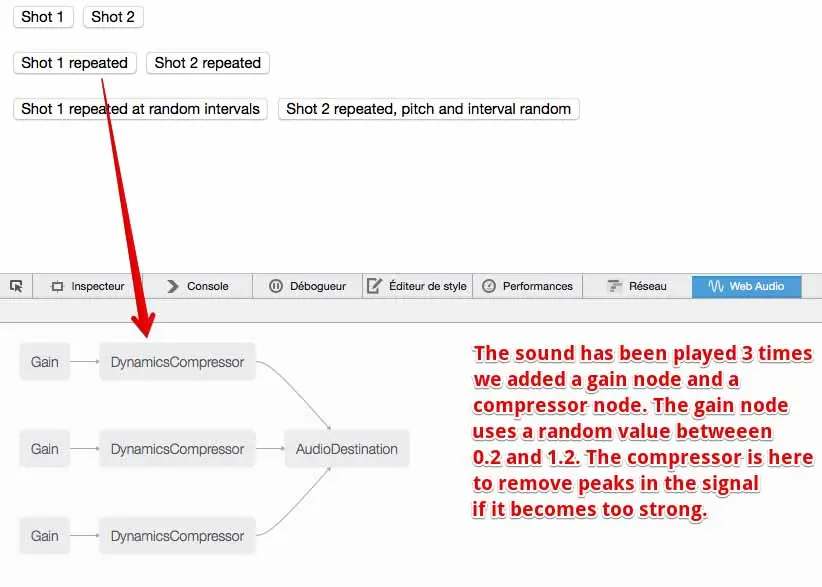

First, we will look at the Web Audio API that helps processing and synthesizing audio in Web applications. You will be able to load sound samples into memory and play them, loop them, process them through a chain of sound effects such as reverberation, delay, graphic equalizer, compressor, distortion, etc. You can also write nice real time visualizations like dancing frequency graphs, animated waveforms that dance with the music, or generate music programmatically.

The Web Audio API is particularly suited for games or for music applications.

A second nice multimedia feature is the Track API.

With it, you will be able to synchronize a video with elements in your document. For example: display a Google Map, an HTML description or a Wikipedia page aside the video, while it’s playing. As always, do not hesitate to practice coding looking at the interactive examples, and then please share your own creations in the discussion forum!

We hope you will enjoy this first week and we wish you the best!

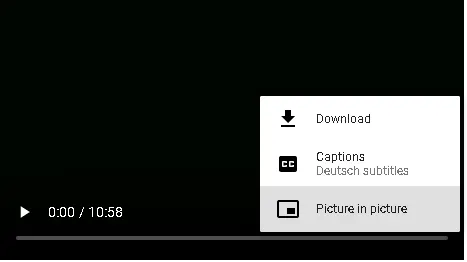

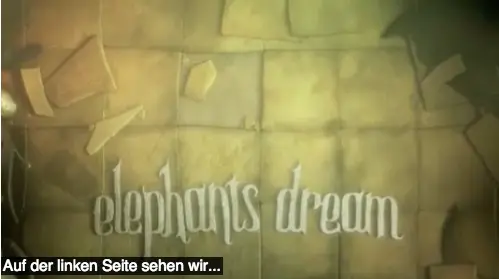

Hi, today I’ve prepared for you a small example of a video that is associated with three different tracks.

Two for subtitles, in English and in German, and one track for chapters.

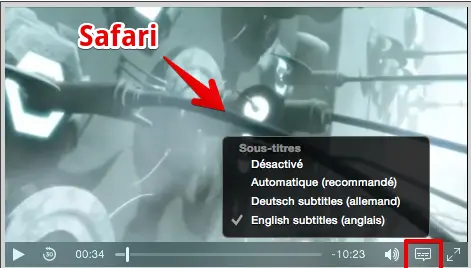

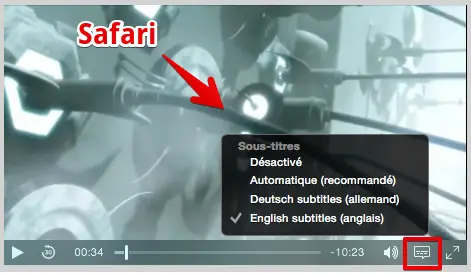

First, before going further, let’s look at how this is rendered in different browsers. With Google Chrome, we’ve got a CC button here, that will enable or disable subtitles. What we can see is that by default the subtitles that are displayed are in German (in this example).

And I can just switch them on and off. It loaded the first track that has the default attribute. And I have no menu for choosing what track, what language I want to be displayed here …

If we look at FireFox, it’s even worse!

We don’t have any menu at all, no CC button. I cannot switch on the subtitles, because as of December 2015, FireFox will load only the first track, if it has the default attribute.

This is not the case, so we don’t have any subtitles and we cannot display them.

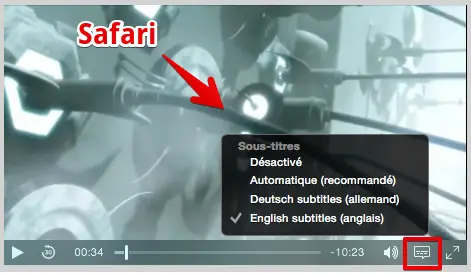

With Safari, on my Mac, it’s better because I’ve got a subtitle menu and I can choose between the different tracks. I can switch to English subtitles, and english subtitles will be displayed.

I’m on a MacIntosh so I cannot show you… but with other browsers like Internet Explorer or Microsoft Edge, there are situations similar to Safari.

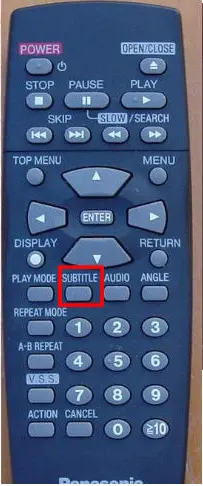

What can we do to increase the features of the default player? We can use what we call the Track API, for asking which tracks are available, activating them, and so on. Now, I would like to remind you the structure of a track. I’m just going to display the content of one of these tracks.

The tracks are made of cues and what we call a cue is a kind of time segment that is defined with a starting time and an ending time. And the cue can have an ID, in that case it is a numeric ID (1, 2, 3), and a content that can be HTML with bold, italic elements and it can also be a voice so when you see “v” followed by the name of the character that is speaking, it’s a voice.

We are going to look at what we can do with such tracks during the course and we will see how to handle a chapter menu, how to display a nice transcript on the side of the video, that you can click to jump at the exact time the video tells the words that are on the transcript. And we will see also how to choose the subtitle or caption track language for the video.

This is finished for this small introduction video, I will just conclude by this thing here: explaining this crossOrigin=“anonymous”. We saw that during the HTML5 Part 1 course and many people asked questions about this. This is because of security constraints.

In browsers, when you’ve got the HTML page that is on a different location than the video file and the tracks files, you will have security constraints errors. And if your server is configured for accepting different origins, then you can add this attribute crossOrigin=“anonymous” in your HTML document and it is going to work.

The server here: mainline.i3s.unice.fr has been configured for allowing external HTML pages to include the videos it hosts and the subtitles it hosts, this is the reason. You can use the DropBox public directory here because Dropbox also enables cross origin requests.

In the W3Cx HTML5 Coding Essentials and Best Practices course, we saw that <video> and <audio> elements can have <track> elements. A <track> can have a label, a kind (subtitles, captions, chapters, metadata, etc.), a language (srclang attribute), a source URL (src attribute), etc. Here is a small example of a video with 3 different tracks (“……” masks the real URL here, as it is too long to fit in this page width!):

<video id="myVideo" preload="metadata" controls crossOrigin="anonymous">

<source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.mp4" type="video/mp4">

<source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.webm" type="video/webm">

<track label="English subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-en.vtt">

<track label="Deutsch subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="de"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-de.vtt" default>

<track label="English chapters" kind="chapters" srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-chapters-en.vtt">

</video>

And here is how it renders in your current browser (please play the video and try to show/hide the subtitles/captions):

Notice that the support for multiple tracks may differs significantly from one browser to another, in particular if you are using old versions.

You can read this article by Ian Devlin: “HTML5 Video Captions – Current Browser Status”, written in April 2015, for further details.

There is a Timed Text Track API in the HTML5/HTML5.1 specification that enables us to manipulate <track> contents from JavaScript. Do you recall that text tracks are associated with WebVTT files? As a quick reminder, let’s look at a WebVTT file:

WEBVTT 1 00:00:15.000 --> 00:00:18.000 align:start <v Proog>On the left we can see...</v> 2 00:00:18.167 --> 00:00:20.083 align:middle <v Proog>On the right we can see the...</v> 3 00:00:20.083 --> 00:00:22.000 <v Proog>...the <c.highlight>head-snarlers</c></v> 4 00:00:22.000 --> 00:00:24.417 align:end <v Proog>Everything is safe. Perfectly safe.</v>

The different time segments are called “cues” and each cue has an id (1, 2, 3 and 4 in the above example), a startTime and an endTime, and a text content that can contain HTML tags for styling (<b>, etc…) or be associated with a “voice” as in the above example. In this case, the text content is wrapped inside <v name_of_speaker>…</v> elements.

It’s now time to look at the JavaScript API for manipulating tracks, cues, and events associated with their life cycle. In the following lessons, we will look at different examples which use this API to implement missing features such as:

Hi, in this video I will show you how we can work with the track elements from JavaScript, just to know which track has been loaded and which track is active. For that, we will manipulate different properties of the HTML track element from JavaScript.

The first thing I am going to do is to add a small div at the end of the document for displaying the different track statuses. I added a div here called trackStatusesDiv with a heading… I am going to add some CSS to visualize this area. Like that, we will have the description of the track here. I added a border and some margins and so on. From JavaScript, we can not do anything before the page has been loaded, so I am adding a window.onload listener, and all the treatments will be in this function.

The first thing I am going to do is get these track elements here… and I am going to get them in a variable called htmlTracks. How can I get them? I’m going to stop the automatic refresh on JSBin for the moment. So, querySelectorAll is a function that will return a collection with all the tracks, an array with all the tracks, all the HTML elements. I am going to call a function called displayTrackStatuses that I write here. I will first iterate on these tracks and display in the console the different values. We are doing a loop.

I will first display something in the console. I am going to add a current track, it will be easier. I can write currentTrack.label for example, that will display the value of the different attributes. This is just for checking that my code is OK. Open the console, I have got one error… If I click here “Run with JS” I can see that it’s working. What I can display is the label, I can also display the kind… you remember the kind: subtitles, subtitles, chapters for the different track subtitles, subtitles and chapters and I can also display the language with srclang. So English, Deutsch (for German).

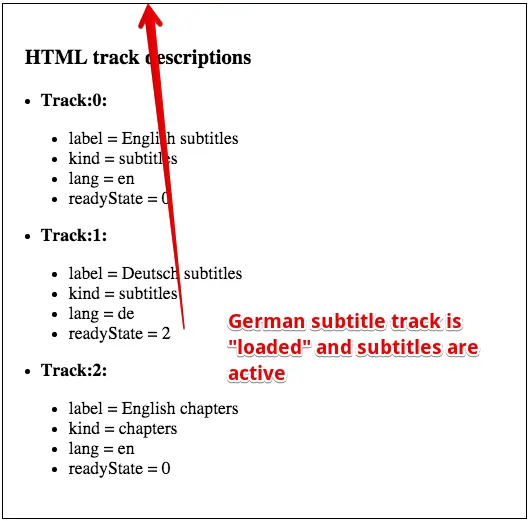

I can also display what is called the status. It is readyState, this is a property you can use only from JavaScript. It says that for track number 1, the value is 0, for track number 2 is 2, for track number 3, it’s 0. 2 means that the track is loaded and 0 means that the track is not available. We’ve got the first track, the English subtitles are not available: status readyState 0 and we’ve got the German subtitles that have been loaded because it has the default attribute, and we showed that in Google Chrome the track with the default attribute is loaded when the page is loaded.

This is how we can consult the different statuses of a track from JavaScript. I am going to copy and paste some code for just displaying this in a nicer way here. This is how we can display the different statuses and I can add a button that will call this just to refresh the different statuses.

Let’s add a button, we call it refresh, and when we click on it, we will call displayTrackStatuses. If I click here… just checking there is no error…it will refresh this thing. So now I am going to try this code with Safari; because you remember Safari has a menu for changing the different tracks.

I prepared that already, so here I can start playing the same video that has Deutsch subtitles loaded by default, you can see that here. If I choose English subtitles now, and I refresh track statuses: you can see that the English subtitles are loaded now and the Deutsch subtitles are also available. We are going to use these different attributes for forcing some tracks to load programmatically from JavaScript and this will enable us to make a sort of menu for choosing the different tracks.

<video id="myVideo" preload="metadata" controls crossOrigin="anonymous">

<source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.mp4" type="video/mp4">

<source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.webm" type="video/webm">

<track label="English subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-en.vtt" >

<track label="Deutsch subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="de"

src="https://</b>...../elephants-dream-subtitles-de.vtt" default>

<track label="English chapters" kind="chapters" srclang="en"

src="https://</b>...../elephants-dream-chapters-en.vtt">

</video>

<div id="trackStatusesDiv">

<h3>HTML track descriptions</h3>

</div>

This example defines three <track> elements. From JavaScript, we can manipulate these elements as “HTML elements” - we will call them the “HTML views” of tracks.

var video, htmlTracks;

var trackStatusesDiv;

window.onload = function() {

// called when the page has been loaded

video = document.querySelector("#myVideo");

trackStatusesDiv = document.querySelector("#trackStatusesDiv");

// Get the tracks as HTML elements

htmlTracks = document.querySelectorAll("track");

// displays their statuses in a div under the video

displayTrackStatuses(htmlTracks);

};

function displayTrackStatuses(htmlTracks) {

// displays track info

for(var i = 0; i < htmlTracks.length; i++) {

var currentHtmlTrack = htmlTracks[i];

var label = "<li>label = " + currentHtmlTrack.label + "</li>";

var kind = "<li>kind = " + currentHtmlTrack.kind + "</li>";

var lang = "<li>lang = " + currentHtmlTrack.srclang + "</li>";

var readyState = "<li>readyState = " + currentHtmlTrack.readyState + "</li>"

trackStatusesDiv.innerHTML += "<li>Track:" + i + ":</b></li>"

+ "<ul>" + label + kind + lang + readyState + "</ul>";

}

}

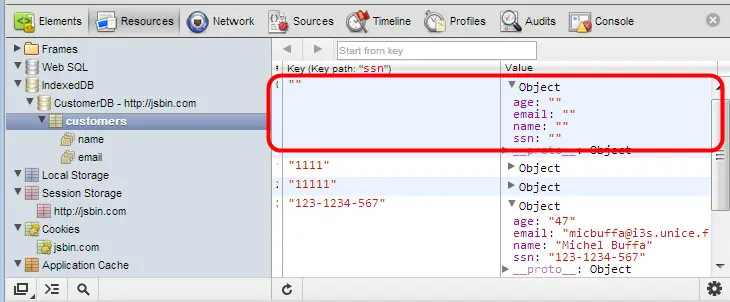

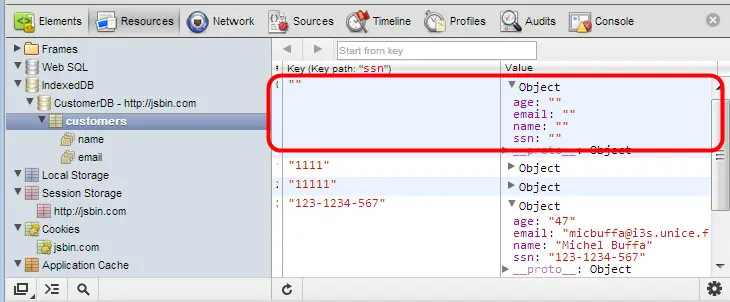

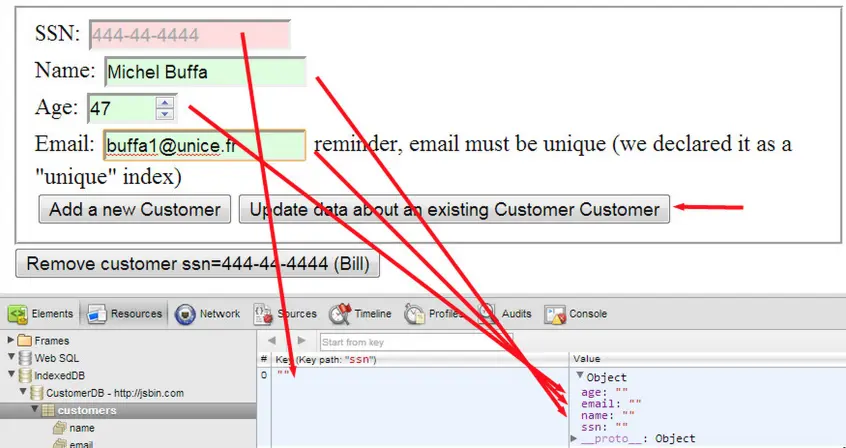

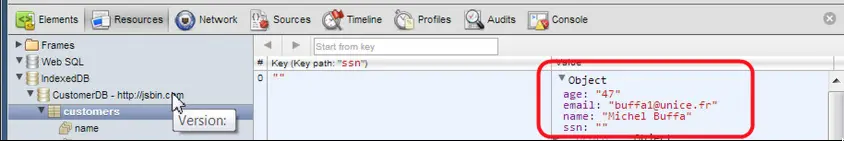

You can see on the screenshot (or from the JSBin example) that the German subtitle file has been loaded, and that none of the other tracks have been loaded.

Now, it’s time to look at the twin brother of an HTML track: the corresponding TextTrack object!

Hi! Now we are preparing ourselves for reading the content of the different text tracks and display them.

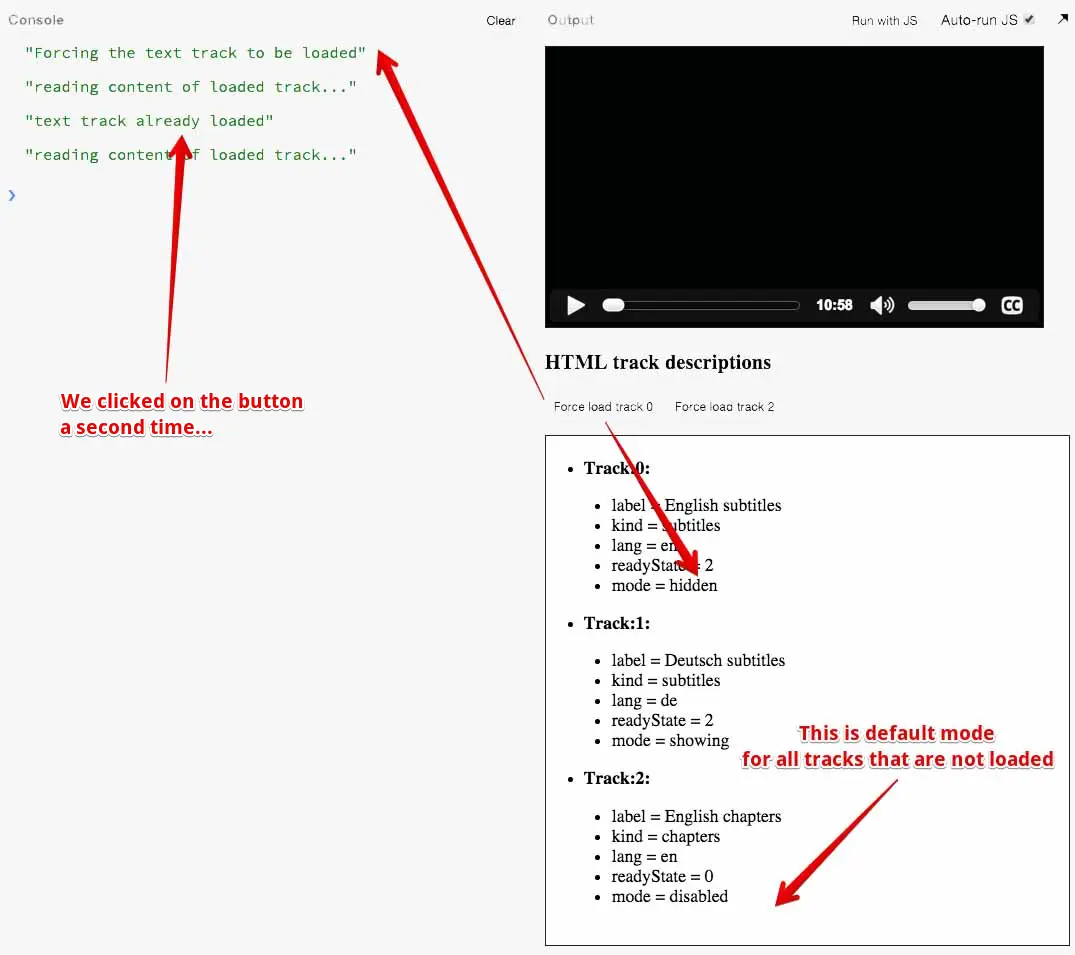

But before that, I must introduce what we call the TextTrack object that is a JavaScript object that is associated to the HTML elements. A track has two different views… maybe it is simpler to say that it has got a HTML view that means you can do a getElementById and manipulate the HTML element, this track element here, from JavaScript. Or we can also work with its twin brother that is a text track, and this new view is the one we are going to use for forcing a track to be loaded, and for reading its content. And for forcing subtitles or caption track to be displayed. We just slightly modify the previous example by displaying the mode

The mode is a property from the TextTrack, not from the HTML track. And this mode can be “disabled”, “showing” or “hidden”. And when it is disabled, reading the video will not fire any event related to the track. We will talk about events later but a disabled track is the same if we have no track at all.

A track that is “showing” is displayed in the video, if the implementation of the video player supports that. And a track that is “hidden” is just not displayed.

How did we manipulate and access this mode property?

The displayTrackStatuses function, that we wrote earlier, displayed the different properties of the HTML track, like the label, the kind or the language. This time, we accessed his twin brother, the TextTrack by using the track property.

Every HTML track element has a track property that is a TextTrack.

Here, from the current HTML track, I am getting the TextTrack (currentTextTrack).

This is the object we use to access the mode and display it here. Another interesting thing is that if we set the mode, if we modify the value of the mode, from “disabled” to “showing” or to “hidden”, it will force the track to be loaded asynchronously in the background by the browser. We added in this example two buttons, “force load track 0” and “force load track 2” because by default, the track 0, the English subtitles, is not loaded. And the chapters, in track number 2, are not loaded either. We are going to force the track 0 to be loaded.

If I click here “force load track 0”, you see that the status changes - the mode changes to “hidden” and the track now is loaded. What happened in the background?

Let’s have a look at the code we wrote. I am going to zoom a little bit…

The button we clicked is this one: “force load track 0” here, called a function named forceLoadTrack(0) that I prepared.

What does this function do?

It will call another function called getTrack that will check if the track is already loaded.

If it is already loaded, then the second parameter here, is a callback function,

It will be called because the track is ready to be read.

In the case the track has not been loaded, we will set the mode to “hidden” and then we will trigger the browser so that it will load asynchronously, in the background, the track.

And when the track is ready, then, and only then, we will call readContent.

Let’s have a look at this getTrack function that we wrote. It says getTrack, please load me the TextTracks corresponding to the HTML track number n.

So here is the function. The first thing we do is that from the HTML track, we get the text track.

Then we check on the HTML track if it is already loaded.

If it is the case, then we will call the function that has been passed as the second parameter: it’s the readContent. And the readContent is just here, for the moment it will not read the content really, but it will just update the status.

If I click on « force load track 2 » for example, it will load the track and when the track is arrived, it will call the displayStatus() that will show the updated status of the track.

In the case the track is not here, the readyState is not equal to 2, then we will force the track to be loaded. By doing this we set the mode to “hidden”.

This may will take some time: you understand that the browser is loading on the Web the track. It may take 2 seconds for example. We need to have a listener that will listen to the load event.

So htmlTrack.addEventListenner(‘load’…) will trigger only when the track has been loaded, and only in that case we will call the callback function: the readContent that has been passed in the second parameter, in order to read the track.

If I look at the console, and if I start again the application. Only the second track has been loaded, I click “force load track 0”, it says “forcing the track to be loaded”, it loads the track and it calls the callback “reading content of loaded track”.

If I click again the same button, it says “the text track is already loaded” and I am going to read it now. We cannot load a track several times, if it is already loaded, we must just use it. In the next video, we will show how we can effectively read the content of the track and do something with it.

The object that contains the cues (subtitles or captions or chapter description from the WebVTT file) is not the HTML track itself. It is another object that is associated with it: a TextTrack object!

The TextTrack JavaScript object has different methods and properties for manipulating track content, and is associated with different events. But before going into detail, let’s see how to obtain a TextTrack object.

Obtaining a TextTrack object that corresponds to an HTML track

First method: get a TextTrack from its associated HTML track.

The HTML track element has a track property which returns the associated TextTrack object.

// HTML tracks

var htmlTracks = document.querySelectorAll("track");

// The TextTrack object associated with the first HTML track

var textTrack = htmlTracks[0].track;

var kind = textTrack.kind;

var label = textTrack.label;

var lang = textTrack.language;

// etc.

Note that once we get a TextTrack object, we can manipulate the kind, label, language attributes (be careful, it’s not srclang, like the equivalent attribute name for HTML tracks). Other attributes and methods are described later in this lesson.

The <video> element (and <audio> element too) has a TextTrack property accessible from JavaScript:

var videoElement = document.querySelector("#myVideo");

var textTracks = videoElement.textTracks; // one TextTrack for each HTML track element

var textTrack = textTracks[0]; // corresponds to the first track element

var kind = textTrack.kind // e.g. "subtitles"

var mode = textTrack.mode // e.g. "disabled", "hidden" or "showing"

The mode property of TextTrack objects TextTrack objects have a mode property, that is set to one of:

TextTrack content can only be accessed if a track has been loaded! Use the mode property to force a track to be loaded!

BE CAREFUL: you cannot access a TextTrack content if the corresponding HTML track has not

been loaded by the browser! It is possible to force a track to be loaded by setting the mode property

of the TextTrack object to “showing” or “hidden”.

Tracks that are not loaded have their mode property of “disabled”.

Here is an example that will test if a track has been loaded, and if it hasn’t, will force it to be loaded by setting its mode to “hidden”. We could have used “showing”; in this case, if the file is a subtitle or a caption file, then the subtitles or captions will be displayed on the video as soon as the track has finished loading.

<button id="buttonLoadFirstTrack" onclick="forceLoadTrack(0);" disabled> Force load track 0 </button> <button id="buttonLoadThirdTrack" onclick="forceLoadTrack(2);" disabled> Force load track 2 </button>

The buttons will call a function named forceLoadTrack(trackNumber) that takes as a parameter the number of the track to get (and force load if necessary).

Here are the additions we made to the JavaScript code from the previous example:

function readContent(track) {

console.log("reading content of loaded track...");

displayTrackStatuses(htmlTracks); // update document with new

track statuses

}

function getTrack(htmlTrack, callback) {

// TextTrack associated to the htmlTrack

var textTrack = htmlTrack.track;

if(htmlTrack.readyState === 2) {

console.log("text track already loaded");

// call the callback function, the track is available

callback(textTrack);

} else {

console.log("Forcing the text track to be loaded");

// this will force the track to be loaded

textTrack.mode = "hidden";

// loading a track is asynchronous, we must use an event listener

htmlTrack.addEventListener('load', function(e) {

// the track is arrived, call the callback function

callback(textTrack);

});

}

}

function forceLoadTrack(n) {

// first parameter = track number,

// second = a callback function called when the track is loaded,

// that takes the loaded TextTrack as parameter

getTrack(htmlTracks[n], readContent);

}

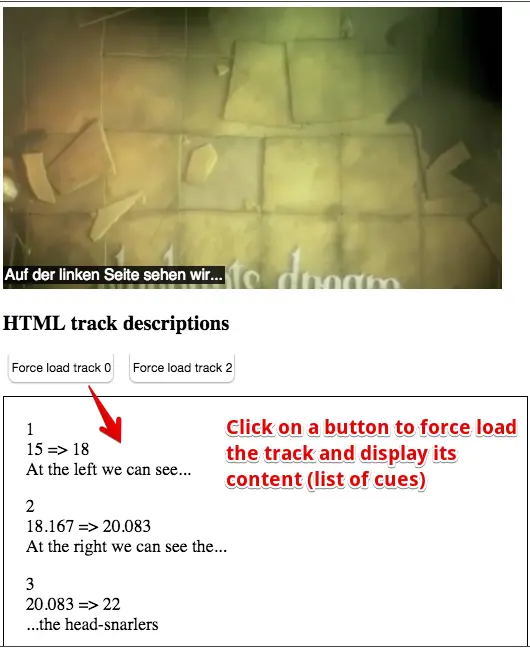

Hi! We will continue the last example from the previous video, and this time when we will click on the “force load track 0” or “force load track 2” buttons.

You remember the track number 0 (the English subtitles) was not loaded, readyState=0 here says the track is not loaded. Track 2 also was not loaded: it contains the English chapters of the video. This time, I will explain how we can read the content of the file. If I click on “force load track 0”, I see here the content of the WebVTT file. I didn’t read it as pure text, I used the track API for accessing individually each cue, each one of these elements here is a cue, and I access the id, the start time, the end time and the content, that we call the text content of each cue. If I click on “force load track 2”, I see the chapters definitions here, so chapter 1 of the video goes from 0 to 26 seconds, and it corresponds to the introduction part of the video.

How did we do that? We just completed the readContent function that previously just showed the statuses of the different tracks. Remember that when we clicked on a button, we forced the text track corresponding to the HTML track to be loaded in memory, and then we can read it. A TextTrack object has different properties and the most important one is called cues. The cues is the list of every cue inside the VTT file, and each cue corresponds to a time segment, has an id and a text content.

If you do track.cues, you’ve got the list of the cues and you can iterate on them.

For each cue, we are going to get its id: cue.id here. It corresponds to the id of the cue number i. In my example, I have got an index in the loop, I get the current cue,

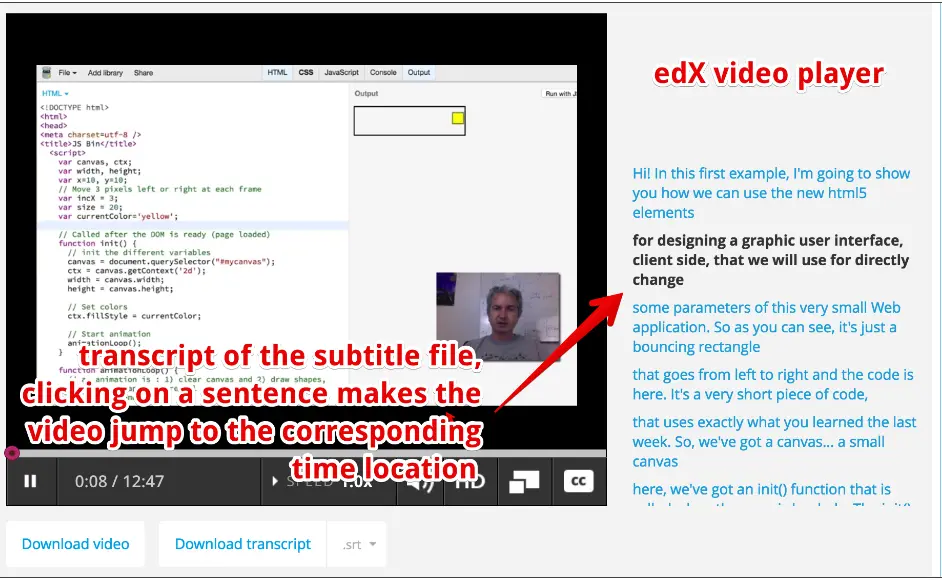

I get the id of this cue. I can also get the start time, the end time and the text. So, cue.text corresponds exactly at this sentence highlighted here. This is the only thing I wanted to show you, because the next time we are going to do something really interesting with this content here, we are going to display on the side of the video a clickable transcript. And when we will click on it, the video will jump to the corresponding position. This is exactly what the edX video player does, the one you are watching at right now.

A TextTrack object has different properties and methods;

A TextTrackCueList is a collection of cues, each of which has different properties and methods;

Here is an example at JSBin that displays the content of a track:

We just changed the content of the readContent(track) method from the example in the previous lesson:

function readContent(track) {

console.log("reading content of loaded track...");

//displayTrackStatuses(htmlTracks);

// instead of displaying the track statuses, we display

// in the same div, the track content//

// first, empty the div

trackStatusesDiv.innerHTML = "";

// get the list of cues for that track

var cues = track.cues;

// iterate on them

for(var i=0; i < cues.length; i++) {

// current cue

var cue = cues[i];

var id = cue.id + "<br>";

var timeSegment = cue.startTime + " => " + cue.endTime + "<br>";

var text = cue.text + "<P>"

trackStatusesDiv.innerHTML += id + timeSegment + text;

}

}

As you can see, the code is simple: you first get the cues for the given TextTrack (it must be loaded; this is the case since we took care of it earlier), then iterate on the list of cues, and use the id, startTime, endTime and text properties of each cue.

This technique will be used in one of the next lessons, and we will show you how to make a clickable transcript on the side of the video - something quite similar to what the edX video player does.

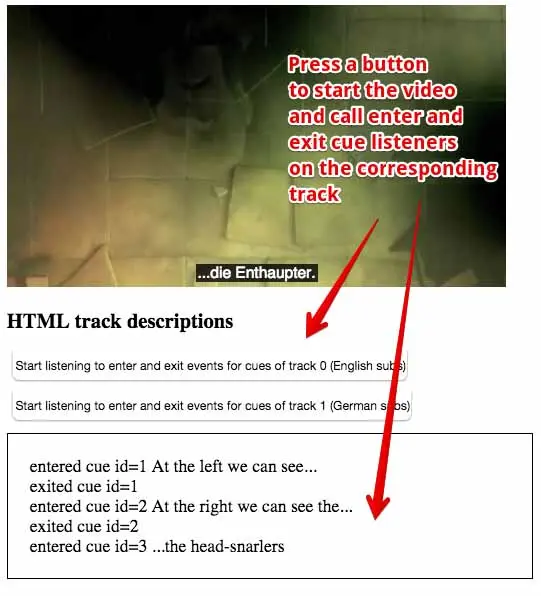

Ok. This time we will talk about track events and cue events.

First, let’s start by a small demonstration. If I play this video, the video is going on and I can listen to events like ‘cuenter’ and ‘cueexit’.

Each time a new cue is entered, we will display it here, and each time it is exited, we will display it here.

We saw that we can display them in sync with the video now. Each time a cue is reached, it means that the current time entered a new time segment defined by the starting and ending time of a cue.

Let’s have a look again at one of the VTT files.

Each cue holds a start time and a end time so when the time enters the 15th second, we’ve got a cueenter event and we can get this content and show it on the HTML page.

When we go out of this time period, when we go further than 18 seconds, we exit this cue and we enter this cue.

How are these events handled in the JavaScript code? Everything is done in the readContent method that we saw earlier.

This time instead of iterating on different cues of the TextTrack, we will just, for each cue individualy, we will iterate on the cues and add a listener on that cue, an exist listener and an enter listener.

So what do we do? We iterate in the cues called addCueListenners for the current cue.

This method, addCueListeners, it will define two listeners: the cue enter listener and the cue exit event listener.

On the cue enter listener we just create a string “entered cue id=” and “text=” that will correspond to the text displayed when a cue is just reached.

We display the id and we display the text.

The same thing is done when we exit.

When we exit, we just display the id “exited cue id=”. This is how we can have individual enter and exit listeners for each cue.

It will enable us to highlight the current cue in a transcript while the video is playing.

The only problem is that as of December 2015, FireFox still does not recognize these sorts of listeners.

The implementation is not done yet, so you can use a fallback. You can use a listener on the track that will listen to the ‘cuechange’ event.

If I just comment the function addCueListeners and I uncomment this piece of code that has a cueChange listener on the track itself, then instead of knowing that we entered of exited and individual cue, we can get, for every new time segment, the list of the cues that are triggered, that should be activated and displayed for this time segment. As the different cues can overlap, the time segments can overlap -it is not often the case but it may occur- what the callback function from this listener gives is a list of active cues. Most of the time you have got only one.

Anyway, you can just work with the list of the cues. Here we just take the first active cue because we are assuming that the cues are not overlapping.

I added a small test here because sometimes we’ve got some strange ghost cues that are active and not defined. I do not exactly what was the problem when I test it but I added this test here to avoid some error messages…

We have got the first active cue and we just display it. We get the id, we get the text and this is all. In that case, if I run the application again, instead of having enter and exit, I will just have cue change events.

It starts at 15 seconds.

I had a small bug here, it is not this.id but cue.id…. we can start again.

This is a fallback for FireFox if you want to display the cues in sync with the video.

The next video will show how to display a transcript here with the current cue highlighted and you can click on them in order to jump to the right place in the video.

After that I think we will have seen the most useful properties, methods, events you can use with tracks and cues…

Instead of reading the whole content of a track at once, like in the previous example, it might be interesting to process the track content cue by cue, while the video is being played.

For example, you choose which track you want - say, German subtitles - and you want to display the subtitles in sync with the video, below the video, with your own style and animations…

Or you display the entire set of subtitles to the side of the video and you want to highlight the current one…

For this, you can listen for different sorts of events.

// track is a loaded TextTrack

track.addEventListener("cuechange", function(e) {

var cue = this.activeCues[0];

console.log("cue change");

// do something with the current cue

});

In the above example, let’s assume that we have no overlapping cues for the current time segment.

The above code listens for cue change events: when the video is being played, the time counter increases. And when this time counter value reaches time segments defined by one or more cues, the callback is called.

The list of cues that are in the current time segments are in this.activeCues; where this represents the track that fired the event.

In the following lessons, we show how to deal with overlapping cues (cases where we have more than one active cue).

// iterate on all cues of the current track

var cues = track.cues;

for(var i=0, len = cues.length; i < len; i++) {

// current cue, also add enter and exit listeners to it

var cue = cues[i];

addCueListeners(cue);

...

}

function addCueListeners(cue) {

cue.onenter = function(){

console.log('enter cue id=' + this.id);

// do something

};

cue.onexit = function(){

console.log('exit cue id=' + cue.id);

// do something else

};

} // end of addCueListeners...

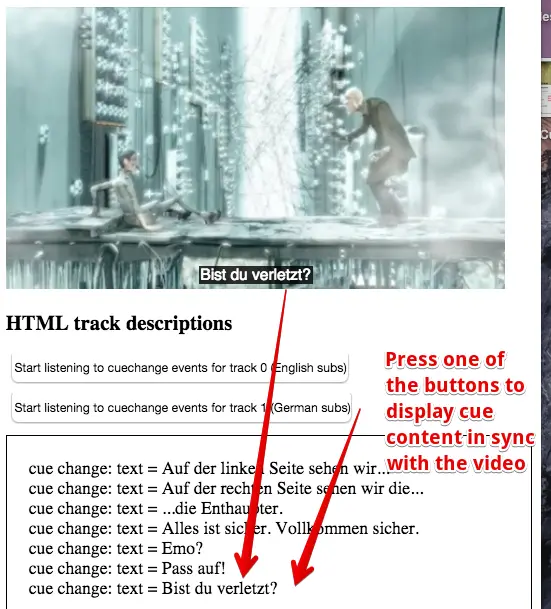

Here is an example at JSBin that shows how to listen for cuechange events:

function readContent(track) {

console.log("adding cue change listener to loaded track...");

trackStatusesDiv.innerHTML = "";

// add a cue change listener to the TextTrack

track.addEventListener("cuechange", function(e) {

var cue = this.activeCues[0];

if(cue !== undefined)

trackStatusesDiv.innerHTML += "cue change: text = " + cue.text + "<br>";

});

video.play();

}

function readContent(track) {

console.log("adding enter and exit listeners to all cues of this > track");

trackStatusesDiv.innerHTML = "";

// get the list of cues for that track

var cues = track.cues;

// iterate on them

for(var i=0; i < cues.length; i++) {

// current cue

var cue = cues[i];

addCueListeners(cue);</b>

}

video.play();

}

function addCueListeners(cue) {

cue.onenter = function() {

trackStatusesDiv.innerHTML += 'entered cue id=' + this.id + " > "

+ this.text + "<br>";

};

cue.onexit = function() {

trackStatusesDiv.innerHTML += 'exited cue > id=' + this.id + "<br>";

};

} // end of addCueListeners...

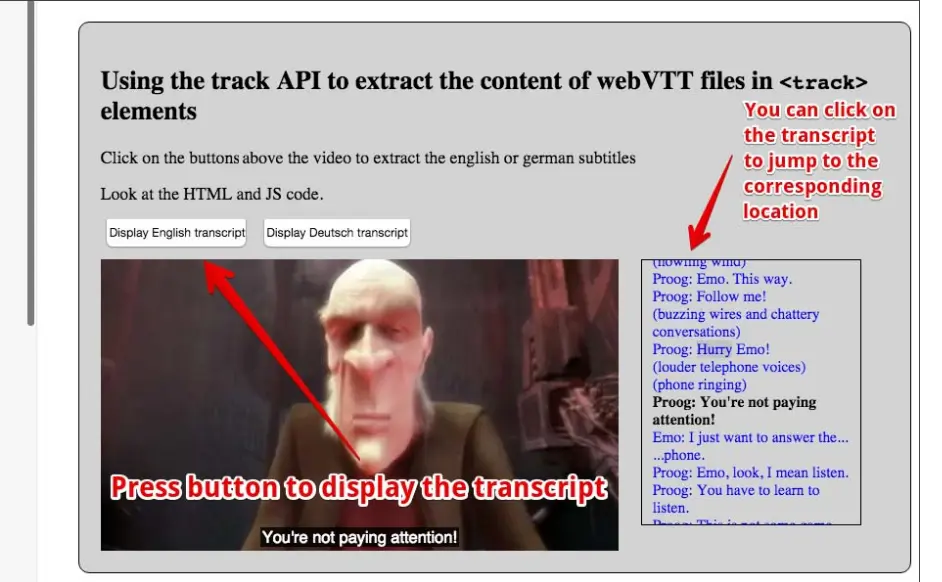

Hi! This time, we will just go a little bit further than in the previous examples.

When we click on a button, we will force the loading of the track, we will read the content, add cue listeners in order to trigger events when the video is played and we will display them on the side this time, and there are hyperlinks you can click and if I click somewhere, the video starts at the corresponding location and you can see that the cues are highlighted in black as the video advances.

There are not a lot of subtitles at this location but… you can see that the transcript is highlighted as the video is playing.

What have we added to the previous example?

The first thing is that we just defined a rectangular area here: it is just a div with an id=“transcript”, and we added some CSS here, for locating the video and the transcript on the same horizontal position, so that the video can grow and the transcript too.

We use floating positions, I put ‘float:left;’ for the transcript that is on the right because if I put ‘right’ it will grow but it will be aligned on the right … and I prefer it on the left.

We can give a look at the CSS, there is nothing complicated and this can scroll because of the overflow:auto; rule we added to the div.

When we click on the buttons here, we call a function called loadTranscript(), instead of forceLoadTrack(0) and forceLoadTrack(1), this time we just ask for a particular language and, it’s implicit, but we are also looking for track files that are not chapters.

Let’s have a look at this loadTranscript() function here. So the loadTranscript() function has a parameter that is the language.

The first thing we do is that we clear the div, we are just setting the content to null and then we disable all the tracks: we set the mode of the all the tracks ‘disabled’ because when we click here and we can change the language of the transcript, we need to disable all track and enable just the one we are interested in.

How can we locate the right track with the language?

We just iterate on the tracks… this is the text tracks object… and we get the current track as an HTML element and as a TextTrack and using the TextTrack, we just check the language and the kind.

And if the language is equal to the one we are looking for, and if the kind is different than chapters, then this is the track we would like.

By forcing the mode to “showing”, in case the track has not already been loaded, it will trigger (it will ask the browser) to load the file.

This is where we test if the file is already been loaded, it is exactly the same test we did in the previous example.

If the track is already loaded, just display the cues in sync with the video and if the track has not been loaded, display the cues after the track has been loaded.

This is the same function as the getContent we had, except that we renamed it.

This takes the track as an HTML element and the TextTrack as parameters.

Let’s have a look at how it is done.

“displayCuesAfterTrackLoaded” just waits for the load event to be triggered and then it called display the cues function that will display the cues in sync.

Either we call it directly if the track is loaded, or we know that the loading has been triggered if necessary, and we just wait in the load event listener.

Let’s have a look at what displayCues function does.

The displayCues function is exactly the same as the readContent we had earlier.

It gets the cue list for the given track, add listeners to the track.

And instead of just displaying the plain text below the video as we did earlier, we will just make a nice format and we will add the id of the cue in the element we are creating.

Let’s have a look… I’m calling the inspector… let’s have a look at one of the list items here.

You can see that in the list item we use the CSS class called cues, just for the formatting, for putting them in blue and adding an underline when the mouse is over, and we use the id of the cue in the list item.

So the id is 10, and we also created an onclick listener that calls the function we will detail later, that is call jumpTo.

And here is the starting time of the cue.

What we did is that we created a list item with a given id and if we click on it, it has a click listener that will call the jumpTo with the time as the parameter.

This is the trick, this onclick listener that will make the video jump to the right position.

How did we create that? We use classical techniques.

We created a string called clickableTransText that is just an HTML list item with the id, the onclick listener that is built with the start time of the cue and we just add this list item to the div.

This function here, addToTranscriptDiv, just adds in the DOM the HTML fragment.

We can give a look at addToTranscriptDiv.

It just does transcriptDiv.innerHTML += this text.

The jumpTo method that makes the video jump… in order to jump to a particular time in the video we are just setting the currentTime property of the video element and we want it to start playing as soon as the jump is done.

So video = document.querySelector(“#myVideo”) is just the video HTML element.

I recommend to look slowly at the code, it is a bit longer because we added some formatting for the voices and so on, but it is not complicated.

Take your time and look at how it’s done….

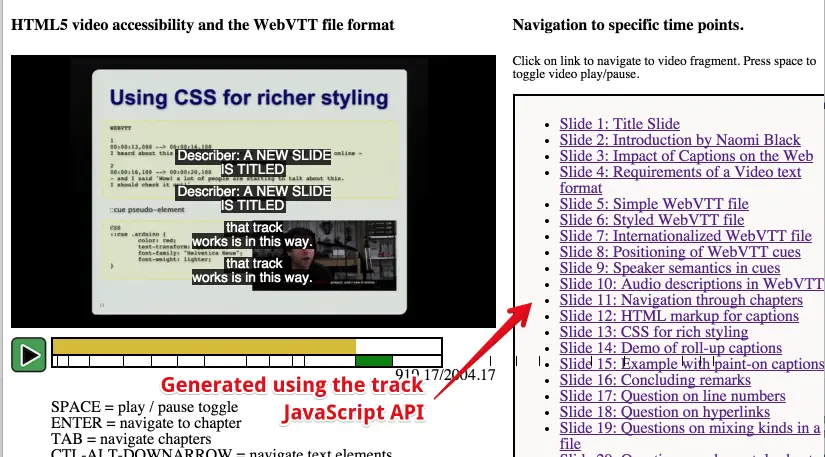

Foreword about the set of five examples presented in this section: the code of the examples is larger than usual, but each example integrates blocks of code already presented and detailed in the previous lessons.

It might be interesting to read the content of a track before playing the video.

This is what the edX video player does: it reads a single subtitle file and displays it as a transcript on the right.

In the transcript, you can click on a sentence to make the video jump to the corresponding location.

We will learn how to do this using the track API.

Read the WebVTT file at once using the track API and make a clickable transcript.

Here we decided to code something similar, except that we will offer a choice of track/subtitle language.

Our example offers English or German subtitles, and also another track that contains the chapter descriptions (more on that later).

Using a button to select a language (track), the appropriate transcript is displayed on the right. Like the edX player, we can click on any sentence in order to force the video to jump to the corresponding location.

While the video is playing, the current text is highlighted.

<section id="all">

<button disabled id="buttonEnglish"

onclick="loadTranscript('en');">

Display English transcript

</button>

<button disabled id="buttonDeutsch"

onclick="loadTranscript('de');">

Display Deutsch transcript

</button>

</p>

<video id="myVideo" preload="metadata" controls crossOrigin="anonymous">

<source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.mp4"

type="video/mp4">

<source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.webm"

type="video/webm">

<track label="English subtitles"

kind="subtitles"

srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-en.vtt" >

<track label="Deutsch subtitles"

kind="subtitles"

srclang="de"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-de.vtt"

default</b>>

<track label="English chapters"

kind="chapters"

srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-chapters-en.vtt">

</video>

<div id="transcript"></div>

</section>

#all {

background-color: lightgrey;

border-radius:10px;

padding: 20px;

border:1px solid;

display:inline-block;

margin:30px;

width:90%;

}

.cues {

color:blue;

}

.cues:hover {

text-decoration: underline;

}

.cues.current {

color:black;

font-weight: bold;

}

#myVideo {

display: block;

float : left;

margin-right: 3%;

width: 66%;

background-color: black;

position: relative;

}

#transcript {

padding: 10px;

border:1px solid;

float: left;

max-height: 225px;

overflow: auto;

width: 25%;

margin: 0;

font-size: 14px;

list-style: none;

}

var video, transcriptDiv;

// TextTracks, html tracks, urls of tracks

var tracks, trackElems, tracksURLs = [];

var buttonEnglish, buttonDeutsch;

window.onload = function() {

console.log("init");

// when the page is loaded, get the different DOM nodes

// we're going to work with

video = document.querySelector("#myVideo");

transcriptDiv = document.querySelector("#transcript");

// The tracks as HTML elements

trackElems = document.querySelectorAll("track");

// Get the URLs of the vtt files

for(var i = 0; i < trackElems.length; i++) {

var currentTrackElem = trackElems[i];

tracksURLs[i] = currentTrackElem.src;

}

buttonEnglish = document.querySelector("#buttonEnglish");

buttonDeutsch = document.querySelector("#buttonDeutsch");

// we enable the buttons only in this load callback,

// we cannot click before the video is in the DOM

buttonEnglish.disabled = false;

buttonDeutsch.disabled = false;

// The tracks as TextTrack JS objects

tracks = video.textTracks;

};

function loadTranscript(lang) {

// Called when a button is clicked

// clear current transcript

clearTranscriptDiv();

// set all track modes to disabled. We will only activate the

// one whose content will be displayed as transcript

disableAllTracks();

// Locate the track with language = lang

for(var i = 0; i < tracks.length; i++) {

// current track

var track = tracks[i];

var trackAsHtmlElem = trackElems[i];

// Only subtitles/captions are ok for this example...

if((track.language === lang) && (track.kind !== "chapters")) {

track.mode="showing";

if(trackAsHtmlElem.readyState === 2) {

// the track has already been loaded

displayCues(track);

} else {

displayCuesAfterTrackLoaded(trackAsHtmlElem, track);

}

/<i> Fallback for FireFox that still does not implement cue enter and exit events

track.addEventListener("cuechange", function(e) {

var cue = this.activeCues[0];

console.log("cue change");

var transcriptText = document.getElementById(cue.id);

transcriptText.classList.add("current");

});

</i>/

}

}

}

function displayCuesAfterTrackLoaded(trackElem, track) {

// Create a listener that will only be called once the track has

// been loaded. We cannot display the transcript before

// the track is loaded

trackElem.addEventListener('load', function(e) {

console.log("track loaded");

displayCues(track);

});

}

function disableAllTracks() {

for(var i = 0; i < tracks.length; i++)

// the track mode is important: disabled tracks do not fire events

tracks[i].mode = "disabled";

}

function displayCues(track) {

// displays the transcript of a TextTrack

var cues = track.cues;

// iterate on all cues of the current track

for(var i=0, len = cues.length; i < len; i++) {

// current cue, also add enter and exit listeners to it

var cue = cues[i];

addCueListeners(cue);

// Test if the cue content is a voice <v speaker>....</v>

var voices = getVoices(cue.text);

var transText="";

if (voices.length > 0) {

for (var j = 0; j < voices.length; j++) { // how many voices?

transText += voices[j].voice + ': ' + removeHTML(voices[j].text);

}

} else

transText = cue.text; // not a voice text

var clickableTransText = "<li class='cues' id=" + cue.id

+ " onclick='jumpTo("

+ cue.startTime + ");'" + ">"

+ transText + "</li>";

addToTranscriptDiv(clickableTransText);

}

}

function getVoices(speech) {

// takes a text content and check if there are voices

var voices = []; // inside

var pos = speech.indexOf('<v'); // voices are like <v Michel> ....

while (pos != -1) {

endVoice = speech.indexOf('>');

var voice = speech.substring(pos + 2, endVoice).trim();

var endSpeech = speech.indexOf('</v>');

var text = speech.substring(endVoice + 1, endSpeech);

voices.push({

'voice': voice,

'text': text

});

speech = speech.substring(endSpeech + 4);

pos = speech.indexOf('<v');

}

return voices;

}

function removeHTML(text) {

var div = document.createElement('div');

div.innerHTML = text;

return div.textContent || div.innerText || '';

}

function jumpTo(time) {

// Make the video jump at the time position + force play

// if it was not playing

video.currentTime = time;

video.play();

}

function clearTranscriptDiv() {

transcriptDiv.innerHTML = "";

}

function addToTranscriptDiv(htmlText) {

transcriptDiv.innerHTML += htmlText;

}

function addCueListeners(cue) {

cue.onenter = function(){

// Highlight current cue transcript by adding the

// cue.current CSS class

console.log('enter id=' + this.id);

var transcriptText = document.getElementById(this.id);

transcriptText.classList.add("current");

};

cue.onexit = function(){

console.log('exit id=' + cue.id);

var transcriptText = document.getElementById(this.id);

transcriptText.classList.remove("current");

};

} // end of addCueListeners...

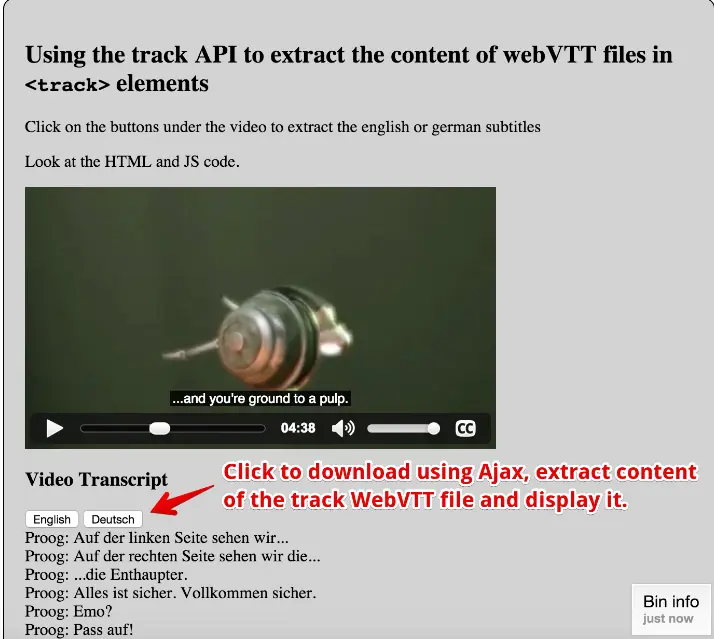

This is an old example written in 2012 at a time when the track API was not supported by browsers. It downloads WebVTT files using Ajax and parses it “by hand”. Notice the complexity of the code, compared to the previous example that uses the track API instead. We give this example as is. Sometimes, bypassing all APIs can be a valuable solution, especially when support for the track API is sporadic, as was the case in 2012…

Here is an example at JSBin that displays the values of the cues in the different tracks:

This example, adapted from an example from (now offline) dev.opera.com, uses some JavaScript code that takes a WebVTT subtitle (or caption) file as an argument, parses it, and displays the text on screen, in an element with an id of transcript.

...

<video preload="metadata" controls >

<source src="https://..../elephants-dream-medium.mp4" type="video/mp4">

<source src="https://..../elephants-dream-medium.webm" type="video/webm">

<track label="English subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="en"

src="https://..../elephants-dream-subtitles-en.vtt" default>

<track label="Deutsch subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="de"

src="https://..../elephants-dream-subtitles-de.vtt">

<track label="English chapters" kind="chapters" srclang="en"

src="https://..../elephants-dream-chapters-en.vtt">

</video>

...

<h3>Video Transcript</h3>

<button onclick="loadTranscript('en');">English</button>

<button onclick="loadTranscript('de');">Deutsch</button>

</div>

<div id="transcript"></div>

...

// Transcript.js, by dev.opera.com

function loadTranscript(lang) {

var url = "https://mainline.i3s.unice.fr/mooc/" +

'elephants-dream-subtitles-' + lang + '.vtt';

// Will download using Ajax + extract subtitles/captions

loadTranscriptFile(url);

}

function loadTranscriptFile(webvttFileUrl) {

// Using Ajax/XHR2 (explained in detail in Module 3)

var reqTrans = new XMLHttpRequest();

reqTrans.open('GET', webvttFileUrl);

// callback, called only once the response is ready

reqTrans.onload = function(e) {

var pattern = /^([0-9]+)$/;

var patternTimecode = /^([0-9]{2}:[0-9]{2}:[0-9]{2}[,.]{1}[0-9]{3}) --> ([0-9]

{2}:[0-9]{2}:[0-9]{2}[,.]{1}[0-9]{3})(.</i>)$/;

var content = this.response; // content of the webVTT file

var lines = content.split(/r?n/); // Get an array of text lines

var transcript = '';

for (i = 0; i < lines.length; i++) {

var identifier = pattern.exec(lines[i]);

// is there an id for this line, if it is, go to next line

if (identifier) {

i++;

var timecode = patternTimecode.exec(lines[i]);

// is the current line a timecode?

if (timecode && i < lines.length) {

// if it is go to next line

i++;

// it can only be a text line now

var text = lines[i];

// is the text multiline?

while (lines[i] !== '' && i < lines.length) {

text = text + 'n' + lines[i];

i++;

}

var transText = '';

var voices = getVoices(text);

// is the extracted text multi voices ?

if (voices.length > 0) {

// how many voices ?

for (var j = 0; j < voices.length; j++) {

transText += voices[j].voice + ': '

+ removeHTML(voices[j].text)

+ '<br />';

}

} else

// not a voice text

transText = removeHTML(text) + '<br />';

transcript += transText;

}

}

var oTrans = document.getElementById('transcript');

oTrans.innerHTML = transcript;

}

};

reqTrans.send(); // send the Ajax request

}

function getVoices(speech) { // takes a text content and check if there are voices

var voices = []; // inside

var pos = speech.indexOf('<v'); // voices are like <v Michel> ....

while (pos != -1) {

endVoice = speech.indexOf('>');

var voice = speech.substring(pos + 2, endVoice).trim();

var endSpeech = speech.indexOf('</v>');

var text = speech.substring(endVoice + 1, endSpeech);

voices.push({

'voice': voice,

'text': text

});

speech = speech.substring(endSpeech + 4);

pos = speech.indexOf('<v');

}

return voices;

}

function removeHTML(text) {

var div = document.createElement('div');

div.innerHTML = text;

return div.textContent || div.innerText || '';

}

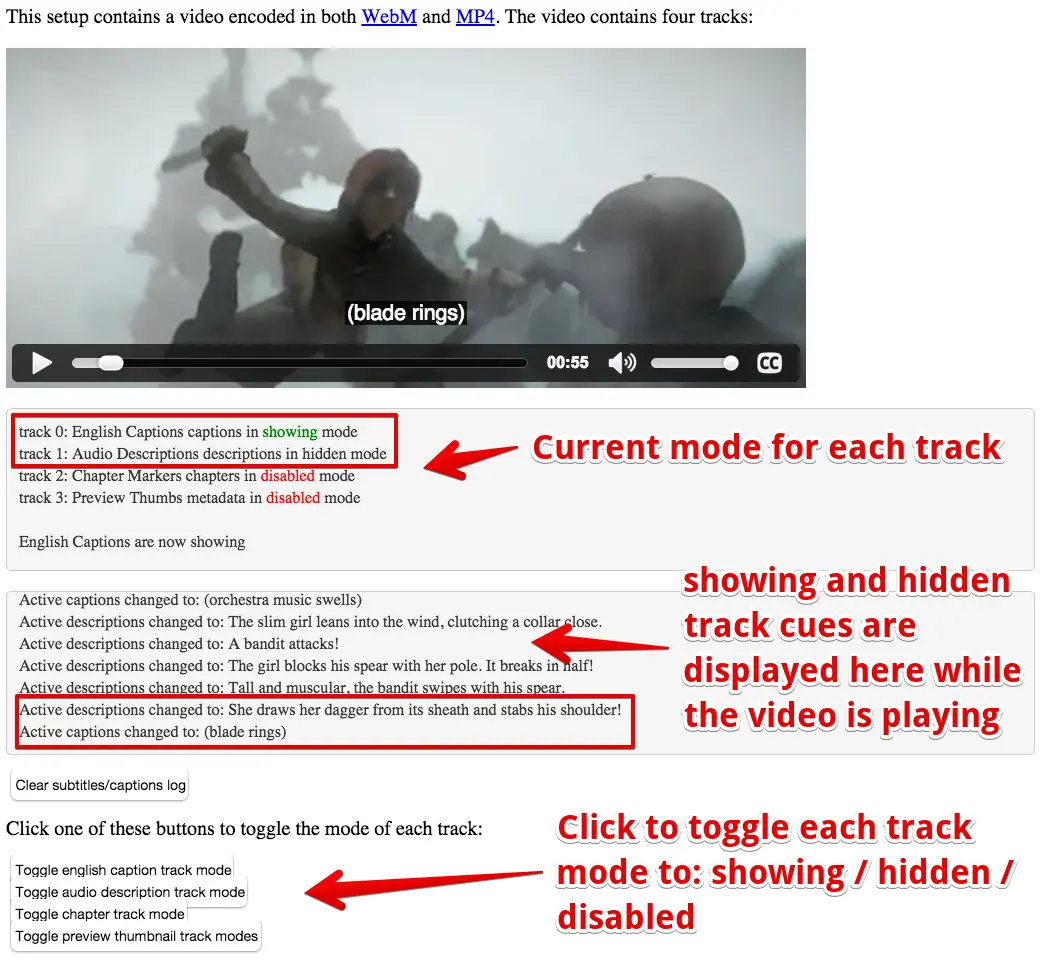

Each track has a mode property (and a mode attribute) that can be: “disabled”, “hidden” or “showing”. More than one track at a time can be in any of these states. The difference between “hidden” and “disabled” is that hidden tracks can fire events (more on that at the end of the first example) whereas disabled tracks do not fire events.

Here is an example at JSBin that shows the use of the mode property, and how to listen for cue events in order to capture the current subtitle/caption from JavaScript. You can change the mode of each track in the video element by clicking on its button. This will toggle the mode of that track. All tracks with mode=“showing” or mode=“hidden” will have the content of their cues displayed in real time in a small area below the video.

In the screen-capture below, we have a WebVTT file displaying a scene’s captions and descriptions.

<html lang="en">

...

<body onload="init();">

...

<p>

<video id="myVideo" preload="metadata"

poster ="https://...../sintel.jpg"

crossorigin="anonymous"

controls="controls"

width="640" height="272">

<source src="https://...../sintel.mp4"

type="video/mp4" />

<source src="https://...../sintel.webm"

type="video/webm" />

<track src="https://...../sintel-captions.vtt"

kind="captions"

label="English Captions"

default</b>/>

<track src="https://...../sintel-descriptions.vtt"

kind="descriptions"

label="Audio Descriptions" />

<track src="https://...../sintel-chapters.vtt"

kind="chapters"

label="Chapter Markers" />

<track src="https://...../sintel-thumbs.vtt"

kind="metadata"

label="Preview Thumbs" />

</video>

</p>

<p>

<div id="currentTrackStatuses"></div>

<p>

<p>

<div id="subtitlesCaptions"></div>

</p>

<p>

<button onclick="clearSubtitlesCaptions();">

Clear subtitles/captions log

</button>

</p>

<p>Click one of these buttons to toggle the mode of each track:</p>

<button onclick="toggleTrack(0);">

Toggle english caption track mode

</button>

<br>

<button onclick="toggleTrack(1);">

Toggle audio description track mode

</button>

<br>

<button onclick="toggleTrack(2);">

Toggle chapter track mode

</button>

<br>

<button onclick="toggleTrack(3);">

Toggle preview thumbnail track modes

</button>

</body>

</html>

var tracks, video, statusDiv, subtitlesCaptionsDiv;

function init() {

video = document.querySelector("#myVideo");

statusDiv = document.querySelector("#currentTrackStatuses");

subtitlesCaptionsDiv = document.querySelector("#subtitlesCaptions");

tracks = document.querySelectorAll("track");

video.addEventListener('loadedmetadata', function() {

console.log("metadata loaded");

// defines cue listeners for the active track; we can do this only after the video metadata have been ed

for(var i=0; i<tracks.length; i++) {

var t = tracks[i].track;

if(t.mode === "showing") {

t.addEventListener('cuechange', logCue, false);

}

}

// display in a div the list of tracks and their status/mode value

displayTrackStatus();

});

}

function displayTrackStatus() {

// display the status / mode value of each track.

// In red if disabled, in green if showing

for(var i=0; i<tracks.length; i++) {

var t = tracks[i].track;

var mode = t.mode;

if(mode === "disabled") {

mode = "<span style='color:red'>" + t.mode + "</span>";

} else if(mode === "showing") {

mode = "<span style='color:green'>" + t.mode + "</span>";

}

appendToScrollableDiv(statusDiv, "track " + i + ":" + t.label

+ " " + t.kind+" in "

+ mode + " mode");

}

}

function appendToScrollableDiv(div, text) {

// we've got two scrollable divs. This function

// appends text to the div passed as a parameter

// The div is scrollable (thanks to CSS overflow:auto)

var inner = div.innerHTML;

div.innerHTML = inner + text + "<br/>";

// Make it display the last line appended

div.scrollTop = div.scrollHeight;

}

function clearDiv(div) {

div.innerHTML = '';

}

function clearSubtitlesCaptions() {

clearDiv(subtitlesCaptionsDiv);

}

function toggleTrack(i) {

// toggles the mode of track i, removes the cue listener

// if its mode becomes "disabled"

// adds a cue listener if its mode was "disabled"

// and becomes "hidden"

var t = tracks[i].track;

switch (t.mode) {

case "disabled":

t.addEventListener('cuechange', logCue, false);

t.mode = "hidden";

break;

case "hidden":

t.mode = "showing";

break;

case "showing":

t.removeEventListener('cuechange', logCue, false);

t.mode = "disabled";

break;

}

// updates the status

clearDiv(statusDiv);

displayTrackStatus();

appendToScrollableDiv(statusDiv,"<br>" + t.label+" are now " +t.mode);

}

function logCue() {

// callback for the cue event

if(this.activeCues && this.activeCues.length) {

var t = this.activeCues[0].text; // text of current cue

appendToScrollableDiv(subtitlesCaptionsDiv, "Active "

+ this.kind + " changed to: " + t);

}

}

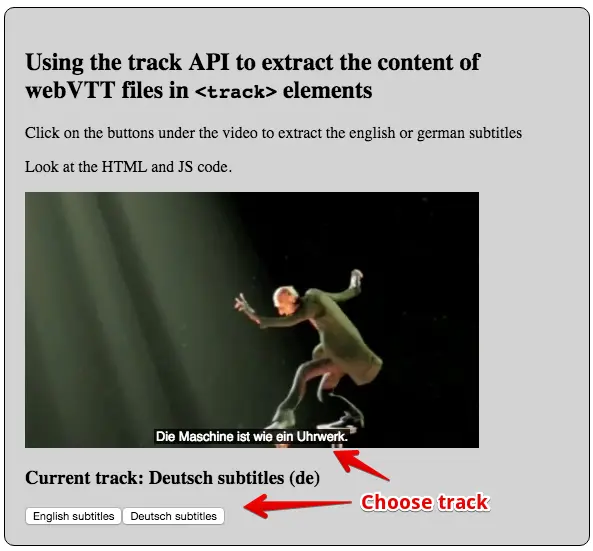

You might have noticed that with some browsers, before 2018, the standard implementation of the video element did not let the user choose the subtitle language. Now, recent browsers offers a menu to choose the track to display.

However, before it was available, it was easy to implement this feature using the Track API.

Here is a simple example at JSBin: we added two buttons below the video to enable/disable subtitles/captions and let you choose which track you prefer.

... <body onload="init()"> ... <video id="myVideo" preload="metadata" controls crossOrigin="anonymous" > <source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.mp4" type="video/mp4"> <source src="https://...../elephants-dream-medium.webm" type="video/webm"> <track label="English subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="en" src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-en.vtt" default</b>> <track label="Deutsch subtitles" kind="subtitles" srclang="de" src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-de.vtt"> <track label="English chapters" kind="chapters" srclang="en" src="https://...../elephants-dream-chapters-en.vtt"> </video> <h3>Current track: <span id="currentLang"></span></h3> <div id="langButtonDiv"></div> </section> ...

var langButtonDiv, currentLangSpan, video;

function init() {

langButtonDiv = document.querySelector("#langButtonDiv");

currentLangSpan = document.querySelector("#currentLang");

video = document.querySelector("#myVideo");

console.log("Number of tracks = "

+ video.textTracks.length);

// Updates the display of the current track activated

currentLangSpan.innerHTML = activeTrack();

// Build the buttons for choosing a track

buildButtons();

}

function activeTrack() {

for (var i = 0; i < video.textTracks.length; i++) {

if(video.textTracks[i].mode === 'showing') {

return video.textTracks[i].label + " ("

+ video.textTracks[i].language + ")";

}

}

return "no subtitles/caption selected";

}

function buildButtons() {

if (video.textTracks) { // if the video contains track elements

// For each track, create a button

for (var i = 0; i < video.textTracks.length; i++) {

// We create buttons only for the caption and subtitle tracks

var track = video.textTracks[i];

if((track.kind !== "subtitles") && (track.kind !== "captions"))

continue;

// create a button for track number i

createButton(video.textTracks[i]);

}

}

}

function createButton(track) {

// Create a button

var b = document.createElement("button");

b.value=track.label;

// use the lang attribute of the button to keep trace of the

// associated track language. Will be useful in the click listener

b.setAttribute("lang", track.language);

b.addEventListener('click', function(e) {

// Check which track is the track with the language we're looking for

// Get the value of the lang attribute of the clicked button

var lang = this.getAttribute('lang');

for (var i = 0; i < video.textTracks.length; i++) {

if (video.textTracks[i].language == lang) {

video.textTracks[i].mode = 'showing';

} else {

video.textTracks[i].mode = 'hidden';

}

}

// Updates the span so that it displays the new active track

currentLangSpan.innerHTML = activeTrack();

});

// Creates a label inside the button

b.appendChild(document.createTextNode(track.label));

// Add the button to a div at the end of the HTML document

langButtonDiv.appendChild(b);

}

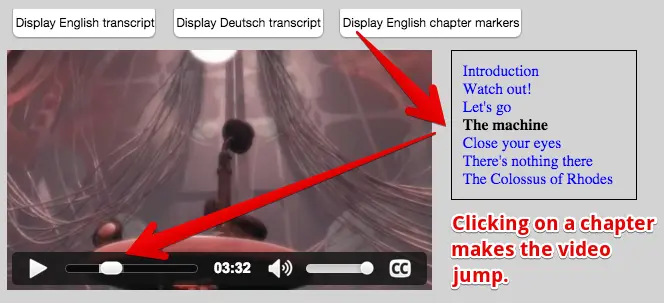

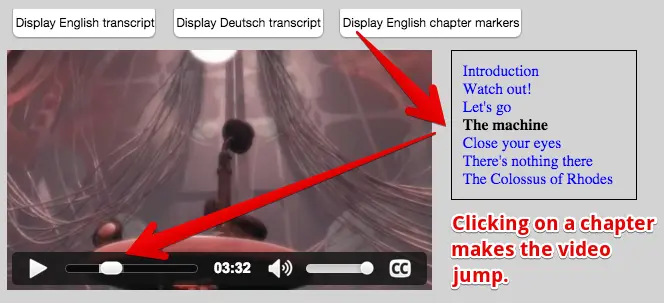

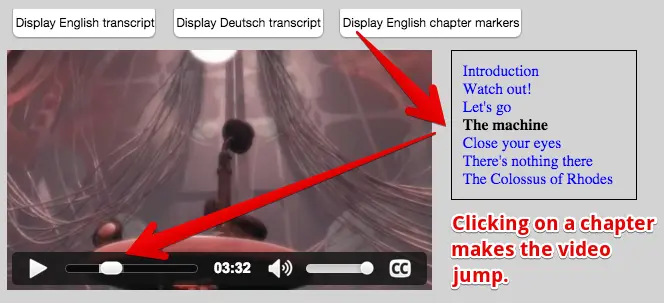

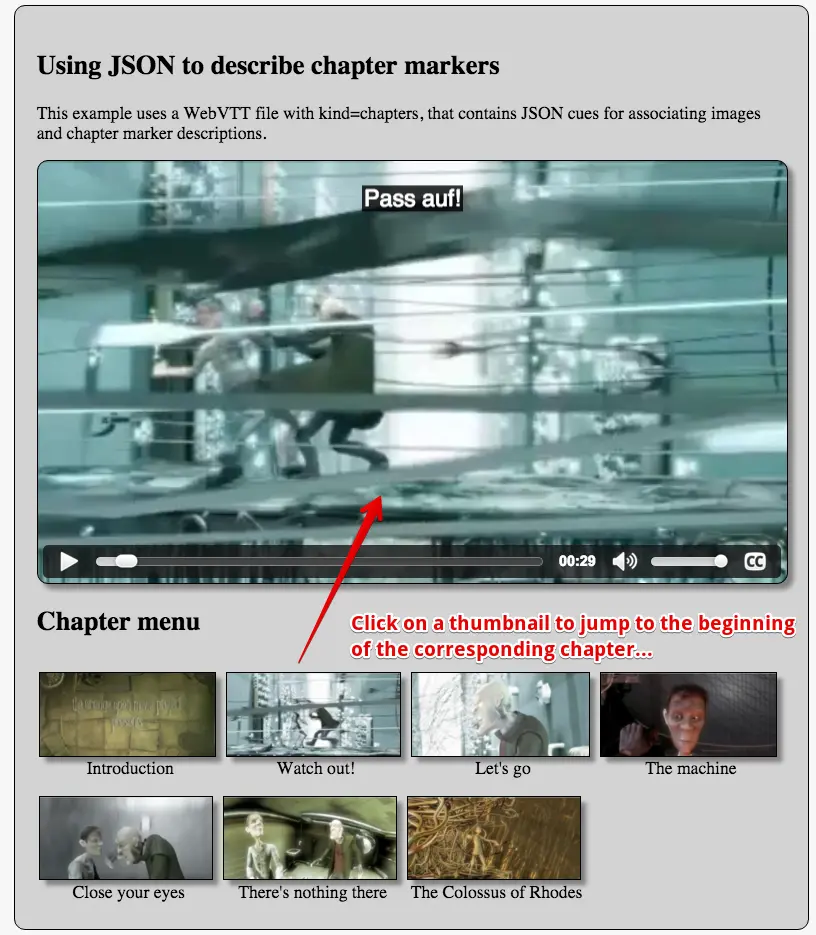

Example #4: making a simple chapter navigation menu

We can use WebVTT files to define chapters. The syntax is exactly the same as for subtitles/caption .vtt files. The only difference is in the declaration of the track. Here is how we declared a chapter track in one of the previous examples (in bold in the example below):

<video id="myVideo" preload="metadata" controls crossOrigin="anonymous">

<source src=<https://...../elephants-dream-medium.mp4>

type="video/mp4">

<source src=<https://...../elephants-dream-medium.webm>

type="video/webm">

<track label="English subtitles"

kind="subtitles"

srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-en.vtt" >

<track label="Deutsch subtitles"

kind="subtitles"

srclang="de"

src=<https://...../elephants-dream-subtitles-de.vtt>

default>

<track label="English chapters"

kind="chapters"

srclang="en"

src="https://...../elephants-dream-chapters-en.vtt">

</video>

If we try this code in an HTML document, nothing special happens. No magic menu, no extra button!

Currently, no browser takes chapter tracks into account. You could use one of the enhanced video players presented during the HTML5 Part 1 course, but as you will see in this lesson: making your own chapter navigation menu is not complicated.

Let’s start by examining the sample .vtt file:

WEBVTT chapter-1 00:00:00.000 --> 00:00:26.000 Introduction chapter-2 00:00:28.206 --> 00:01:02.000 Watch out! chapter-3 00:01:02.034 --> 00:03:10.000 Let's go chapter-4 00:03:10.014 --> 00:05:40.000 The machine chapter-5 00:05:41.208 --> 00:07:26.000 Close your eyes chapter-6 00:07:27.125 --> 00:08:12.000 There's nothing there chapter-7 00:08:13.000 --> 00:09:07.500 The Colossus of Rhodes

There are 7 cues (one for each chapter). Each cue id is the word “chapter-” followed by the chapter number, then we have the start and end time of the cue/chapter, and the cue content. In this case: the description of the chapter (“Introduction”, “Watch out!”, “Let’s go”, etc…).

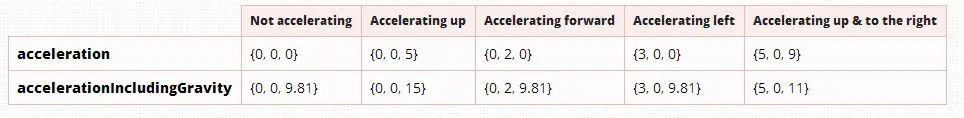

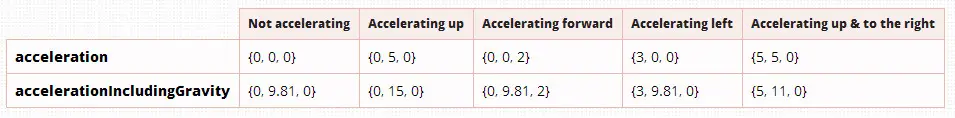

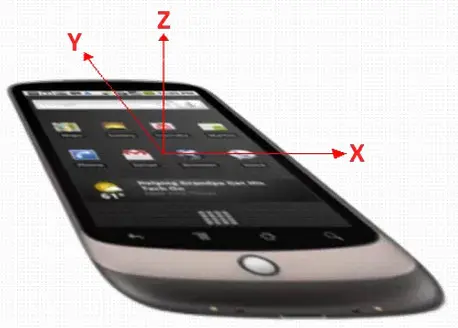

Hmm… let’s try to open this chapter track with the example we wrote in a previous lesson - the one that displayed the clickable transcript for subtitles/captions on the right of the video. We need to modify it a little bit: